No products in the cart.

Motorcycle Culture, Tim Hart, Uncategorized

Motocross Looked Like This: Tim Hart

“We were just kids who wanted to race.”[i]

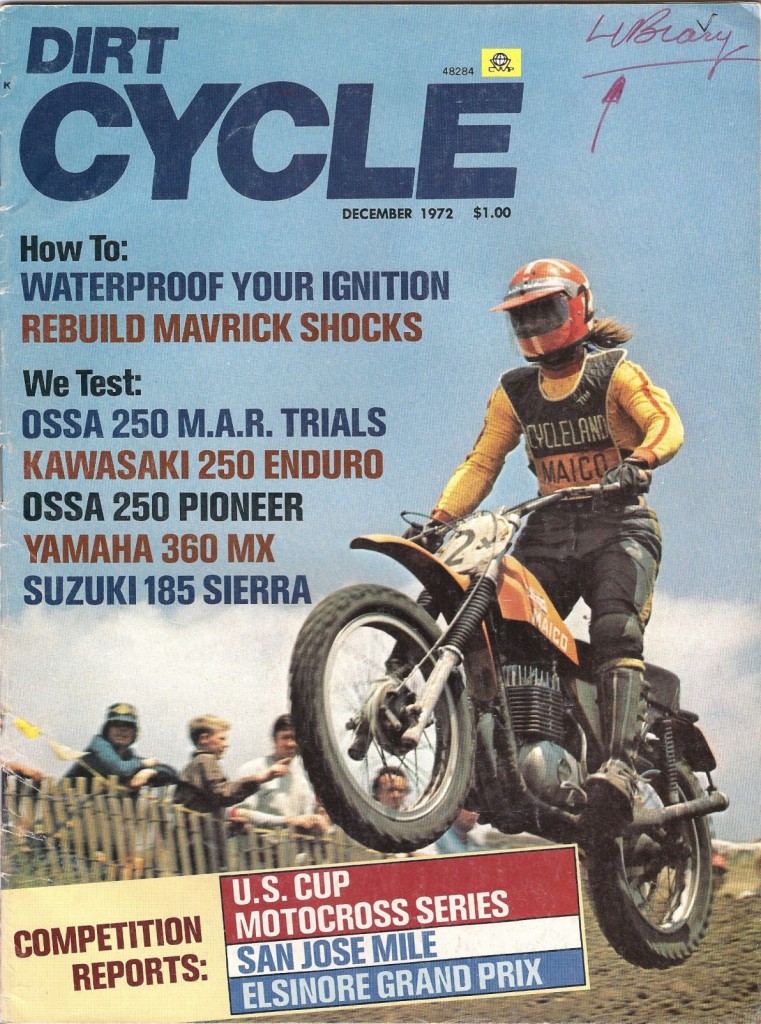

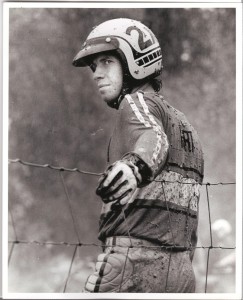

One of the most recognized images of off-road riding, and possibly the sport’s most iconic photograph, comes from the early years when motocross first captured the American imagination. It is that of a lone, airborne motocross racer. The image was first seen on the December, 1972 cover of Dirt Cycle magazine. The photograph is that of a single rider, standing on the foot-pegs of a flying square-barrel Maico 250, evidently having just launched from the crest of a jump. The motorcycle appears to be descending; awaiting reconnection with the ground. The rider’s face is hidden, but the viewer notes that “TIM” is stitched onto the chest protector he is wearing. He wears bulky leather pants and boots. Long hair streams from under the rider’s helmet, held straight by the slipstream. Several fans are visible beyond the snow-fence; some look at the photographer (and now the viewer), while others focus their attention elsewhere. The sun is out and the sky is blue. Taken collectively, the elements form a romantic picture of 1970s racing. The motorcycle traditionally conveyed ideas of speed, danger, power, freedom, and excitement. More recently, since the 1960s, popular motorcycling connotations seem to have changed, and began to include more suggestions of violence, glamour and sexuality. At the beginning of the motorcycle boom in the United States (in the late 1960s), however, we can state that, with the notable exceptions of print advertisements by the British motorcycle industry and Hollywood’s promotion of outlaw biker movies, images of motorcycling tended towards excitement, youth, and physicality.[ii] Racing coverage further focused these latter ideas, and the image of Tim Hart, described above, is an example. This type of image, conveying the excitement of off-road motorcycle riding in general and that of motocross racing, specifically, accelerated the interest of youth across the United States. For many young males in the country, Hart’s image and ones like it, of young men flying an exotic motorcycle off a jump, was the distillation of their dreams for the immediate future.The Boy Next Door

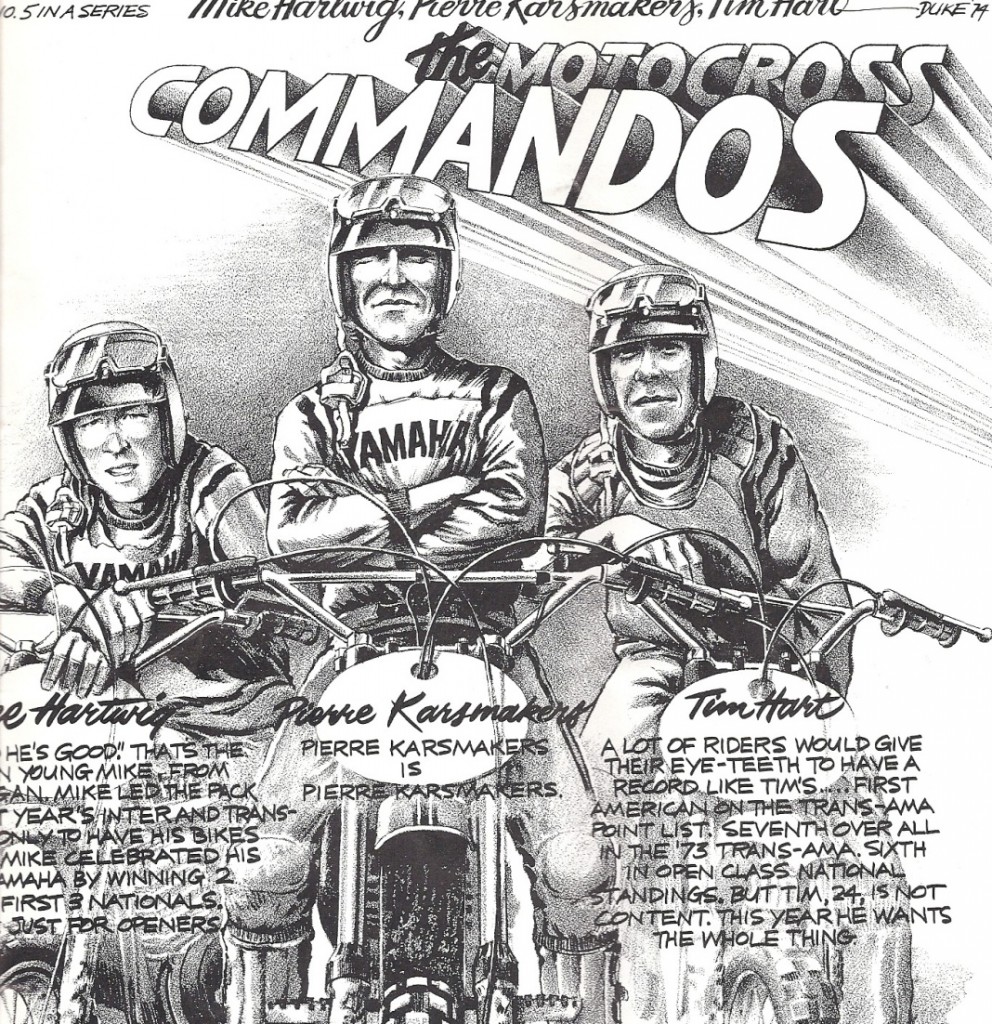

Having discussed in a previous article a key figurehead for both Maico and off-road sport riding, Ake Jonsson, I will now turn to one of the early native-born professional motocross racers in the United States. Unlike Jonsson, Tim Hart raced exclusively in the United States. He represented a more localized idea of a professional racer to other American hopefuls; Hart was, as a sponsored “boy next door,” a peer that American young men could readily identify with. He personified what they aspired to be, with hard work and luck. Beyond his personal racing results, I believe Hart’s greatest legacy to be the rich images of him in action; particularly the two photographs that will be analyzed in the next pages. Also discussed is a mid-1970s advertising illustration featuring Hart and Yamaha teammates Pierre Karsmakers and Mike Runyard, containing allusions to military struggle. In summary, Hart’s images are key markers for the meaning of early motocross racing to American observers at the time. When deconstructed, they can also inform us about the men, the motorcycling subculture, and the greater United States culture in which they existed.

Tim’s Merge with Yamaha

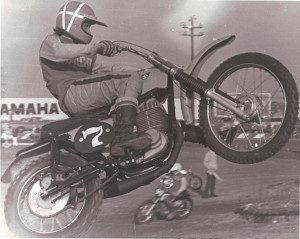

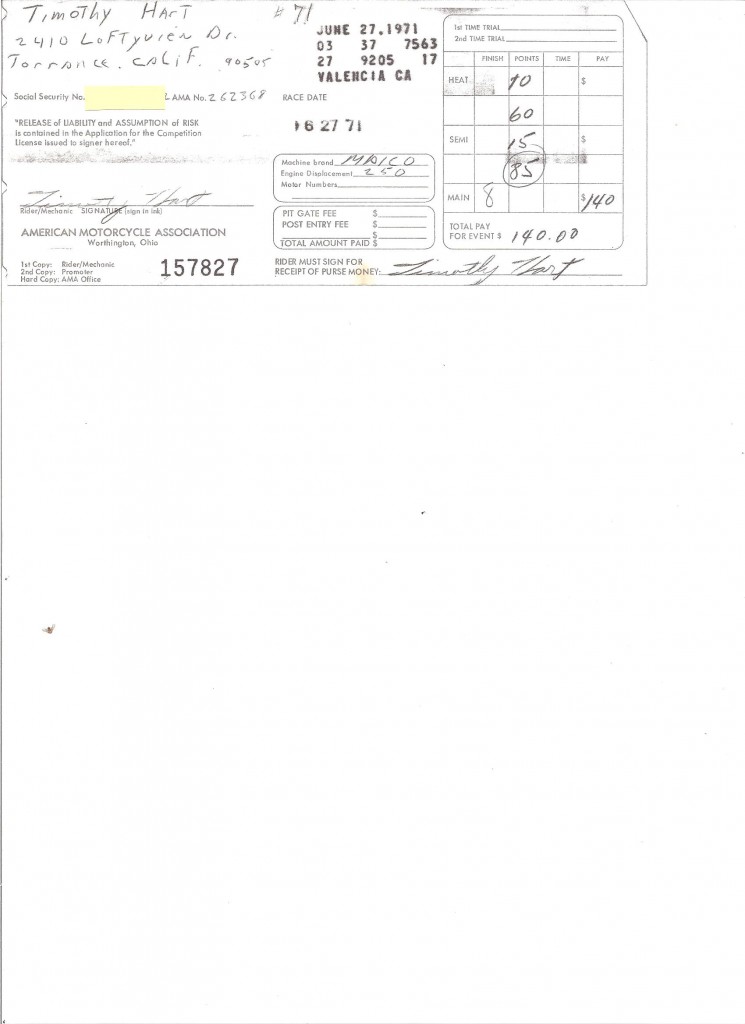

Near the end of 1972, Yamaha had taken note of the young racer’s successes, and offered Hart a more lucrative sponsorship. Yamaha’s agreement with Hart illustrated the evolving model of a factory racing sponsorship, and was far more generous than the motorcycles-and-parts-only allowances offered by the harder-pressed, smaller European factories. Not only were the riders paid salaries, but the deal included expert mechanical support and transportation. Hart recalls, “I rode for Maico from May of 1971 to the end of 1972—though it seems like longer. After that, Yamaha hired me. Pierre Karsmakers was my trainer and got me really into shape back then.[vi] I rode for Yamaha for three years and did pretty good. I didn’t win a lot, but I did win a National . . . and did all-right. It was great; it spoiled me. We worked out twice a week. We would fly to the races Friday, practice on Saturday, ride Sunday, and fly home Sunday night. We’d have one rest day off, and then I’d go to Pierre’s house and we would train . . . and then practice on our bikes, Tuesday through Thursday. That was our schedule. It was a great job. We used to get on the plane and carry an engine on in our luggage . . . maybe bring a frame back to our mechanics, who were always on the road. I had a great mechanic; Ed Schiedler was his name. Pierre had Bill Buchka as his mechanic. Those guys were involved with Yamaha for many years after that, too.”

(Photograph attributed to Jim Gianatsis)

Photography as a Journalistic and Documentary Medium

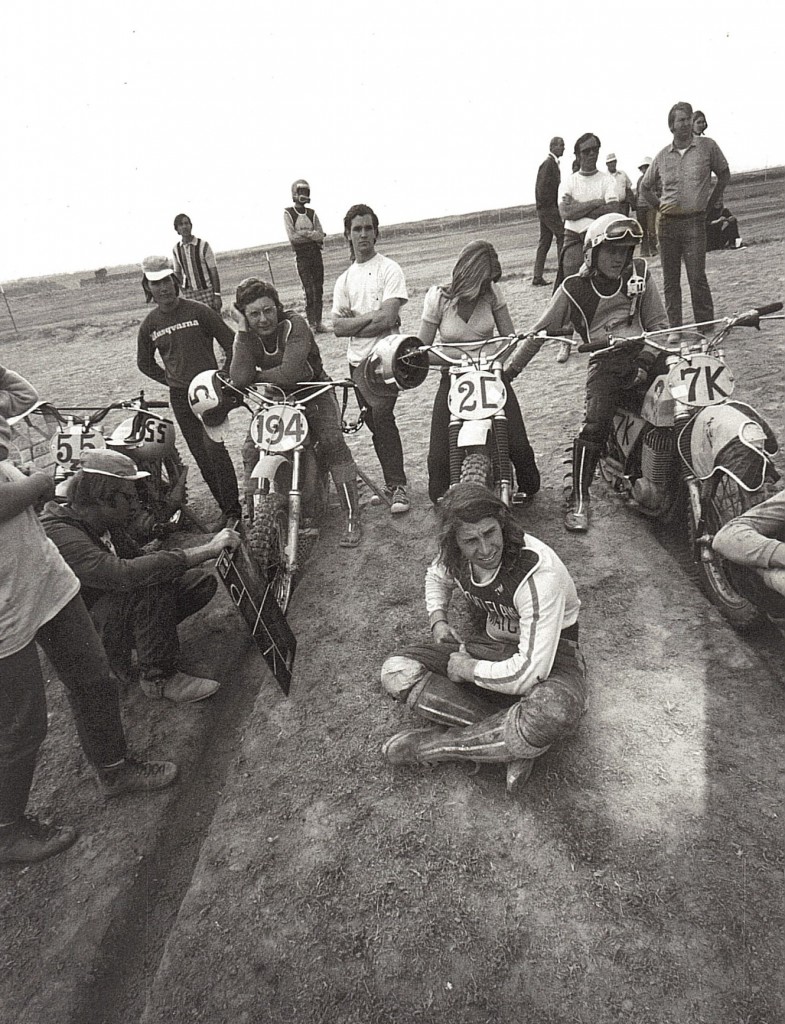

Americans, prior to today’s digital manipulations, have long thought of photography as a factual medium. Alan Trachtenberg, however, has suggested that many American photographs, from historical work to even family snapshots, are best understood as “constructions,” as opposed to verbatim visual transcriptions of an event in time.[viii] That being said, surely non-posed, factual images still remain; at least we certainly hope this is the case with that segment of photography we refer to as documentary or journalistic. Beyond the documentary/journalistic category, we find several definitions and cross-categories: the “social photography” of Lewis Hine and Dorothea Lange; the “fine art photography” of Alfred Stieglitz and Ansel Adams; and endless variations of other images to suit other purposes. Trachtenberg allows that photographs can still be evidence and convey fact, but warns that the viewer should be careful in the process of interpretation. The two photographs, of the three selected images, are of a documentary/journalistic nature. We can assume the photograph of Hart jumping his motorcycle, at what appears to be an actual race, spectators and all, was not in any way staged. Likewise, the photo of Lindstrom, Hart, Chaplin and others, apparently prior to the start of another race, appears largely natural and un-staged. Of course, the photographer could have motioned to one man to move slightly; for the girl to sit on the motorcycle, for another man to stand elsewhere. The fact that the subjects in the frame knew their picture was being taken, and are directing their gaze at the photographer (and now at the viewer), confirms that some interruption of the scene did occur; the attention of most of the subjects elsewhere suggests a minimum of manipulation on the photographer’s part. Both the photos are a microcosm of the American condition of the last 150 years: that of nature invaded by the machine. The “pastoral ideal” of the prairie-like landscape, so traditionally linked with America and described at length by Leo Marx, has been complicated through the introduction of technology into the picture; in this case, motorcycles.[ix] The machine is very much in the two “gardens,” and it is fast and loud. Man is highly evident in both photos, utilizing the machines/motorcycles in what the naturalist might consider a domination of or a contest with nature, while the less machine-phobic observer might more charitably consider the relationship as one binding the man to nature. The machine might be intruding to an extent, but it also brings man into nature, and gives him elemental experiences that are faster-higher-stronger: citius, altius, fortius, as the Olympic motto reminds us. To be fair, we must allow that many off-road motorcyclists do describe their activity as that of a contest between two entities: themselves-and-motorcycle, versus nature. Still, the figures in the second photograph are at ease, doing or preparing to execute their task of navigating motorcycles over and through the earth, for their enjoyment. In this case, one can dispute Marx’s contention that nature and technology, previously reconciled, must always remain in opposition to one another. The riders may be contending with nature, but they also exist very close to it, and would likely profess their love and respect for the natural environment. The participants are very nearly within the earth; touching, resting on, and deeply intertwined with it. The dirt itself covers their machines and themselves; it is part of this world and the riding process, and they are not ashamed of it. The two photographic images also reveal a vernacular response to the impact of the motorcycles with nature. This furthers our understanding of early off-road motorcycling as a non-elite past-time and sport. John Kouwenhoven contends that this type of homespun, “anonymous and undignified” response—the snow-fences, the improvised clothing, the rough and impromptu re-shaping of the environment—is the result of “the peculiar blend of technology with democracy . . . as opposed to merely technological forms.”[x] Hart, his companions, the people who built the race-track, and even the people watching, are left to their own devices in the way they appear and in the ways they have structured the track environment. The two Hart photographs present an early, more individualistic, more nonconformist period of motorcycle culture in the United States. In later generations, these factors (what the racers and spectators wore, and how the motorcycles appear) would be much more highly influenced and constrained by established motor-sports fashion convention. At the time of the pictures, however, this more rigid paradigm had yet to be formulated. The 1970s were, as David Frum writes, the time of the “democratization of social life.” When the pictures were taken, Hart and his friends were pioneers, inhabiting a brand-new, democratic 1970s riding culture; fashion (and other) rules for the new sport were not yet established.[xi] In a few more years, a recognized and much more binding fashion ethic was in place.Analysis of the images

In the image of Tim Hart airborne on his Maico, from the Dirt Cycle cover of December, 1972, we see that the sky is blue and the sun is shining; it appears to be warm when and where this picture was taken. From most places other than the southern California location where the picture likely originates, the balmy scene had to be intoxicating. The handwriting on the upper right of the magazine cover states “Library,” so we can assume this magazine inhabited the shelves of a school library, imported there by some sympathetic librarian. The young teenage boys who picked up the magazine were probably struck right away by the climatic difference between what appeared in the photograph and that of their own locales. A November/December day in St. Paul, Minnesota; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Yakima, Washington; Hickory, North Carolina; or most other places would have differed greatly. The lure of the California myth, so powerful an archetype during that era, is extolled in the picture. The mid-ground/background of the scene (we can only see about fifty yards from the photographer’s location) reveals several on-lookers behind a snow fence. Of the five heads that are visible, three look generally towards Hart and the viewer, with the eyes of the hat-wearing man on the left of the image seemingly looking through Hart, directly into our eyes. His mouth is slightly open; perhaps impressed by the flying motorcycle, and as if he had something pressing to convey. Our gaze flows around the image in a somewhat triangulated eye movement; from the onlooker on the left, to the motorcycle, to Hart’s hidden eyes, and back to the hat-wearing onlooker on the left. The motorcycle and rider are, of course, the focal point of the image. The sun-dappled man and machine are caught by a fast camera shutter in mid-air, apparently after launching from the crest of the bare dirt hill, behind. The motorcycle itself is a 250cc Maico “square-barrel,” made from 1968 through 1971. It appears to be unaltered from factory condition, with the exception of the CHAMPION spark plug sticker on the gas tank and the fitting of an alloy rim on the front, yet retaining a steel rim on the back.[xii] The motorcycle is painted orange; the color of sweet fruit from warm, tropical places. It is a simple, bright, unnatural, attention-inviting, fun color.

Hart was no Hippie!

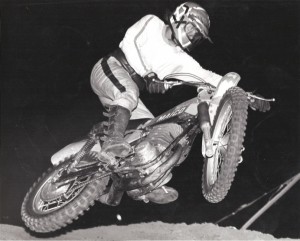

Behind the image are realities. First, we now know that despite the long hair, Hart was no hippie. He was the hard-working son of a blue-collar family. In fact, California, the mythic land of the 1960s counter-cultural and rebellion, was never as surreal as recent legend portrayed it. Southern California, particularly, was populated overwhelmingly by the sort of middle-class, conservative people that Hart was descended from.[xiii] We might think of these people as the descendants of Steinbeck’s Joad family, refugees from hardscrabble Depression America who found work and a future in greater Los Angeles.[xiv] Their jobs were frequently in factories, involving machinery, and the motorcycle industry was not an unlikely occupation for such a worker in Southern California. We also know that Cycle Land Maico, in reality, was just a small motorcycle shop in Gardena, California, operated by similarly hard-working, enthusiastic men, embracing a new era of motorcycle sport. The warm climate and dynamic excitement inherent in the photograph were, of course, very real, and may indeed have been a world apart from the environments and life experiences of most of the viewers of the photo. The image is not at all staged, yet it elicited its own unique constructions in the minds of viewers. The second image shows Gunnar Lindstrom, Tim Hart, Gary Chaplin and others on a starting line at an unidentified race-track, in an un-credited photograph (possibly by Jim Gianatsis) in Dirt Bike Magazine, November, 1973. This image appeared in Dirt Bike, along with other un-credited images, illustrating an essay entitled “Results of the Second Great First Annual Dirt Bike Bench Racing Contest,” a collection of humorous reader essays. The depicted scene is clearly the starting line at a motocross race, captured by a fairly-short focal-length lens on black and white film. Given the earlier square-barrel Maico motorcycles in the photograph, it probably dates to early 1972. The location of the racetrack is not known, but we can see that the background is very flat with no mountains. The location might be other than southern California; perhaps the American mid-west. Those figures which can be identified are: Swedish immigrant and racer Gunnar Lindstrom, sitting on his Husqvarna #194; Tim Hart’s then-girlfriend Julie Grig, sitting on Hart’s #2C Maico; Hart, sitting on the ground; and California racer Gary Chaplin, sitting on Maico #7K. Another Maico, #55Z, stands to the left of the image. Given that Chaplin’s bike is a 250cc machine, and all three racers were known to specialize in this class, the race is almost certainly a 250 class race. Various other figures populate the scene. These include a man holding a signboard (perhaps the start signal), two young men behind Lindstrom (possibly mechanics), a helmeted racer in the background, and others. The gazes of most of the figures in the photograph appear to be fixated on something happening off the image’s right (to the right-rear of the photographer-viewer). Lindstrom, relaxed and leaning on his handlebars, stares at the photographer. Grig looks downward, her face hidden. Chaplin is reaching his right hand over to Hart’s motorcycle, on which Grig is sitting. We cannot determine if he is steadying the motorcycle, touching Grig, or just stretching his arm. This ambiguity may be the reason for Dirt Bike’s inclusion of the image in the humor-oriented “Bench Racing” special feature. The strengths of the photograph are in its composition and richness of content. Hart’s long hair, again, reflects a prevailing personal style norm for a young man of the era, and dates the image. (He now dismisses the hair as “a 1970s thing.”) The presence of the beautiful, blonde Grig, even without her face being visible, injects interest and a curious female presence into the otherwise all-male situation. Grig’s archetypal “California girl” appearance further links the image to the idealized, “sun and fun” west coast lifestyle. Lindstrom’s utter calm and Chaplin’s mysterious right arm add to the visual interest of the assembly. We wonder: What are they looking at? And what are they waiting for? To young boys, the scene was especially inviting: the independent young racer, his lovely girlfriend, exotic motorcycles, and racing as an occupation. There is literally nothing for a young male viewer not to like here, and much which would be explicitly, extremely attractive. From this image, mythic appeal gestates. Additional details further inform the viewer about early motocross racing in the United States. The right knee of Hart’s leathers appears to be repaired with duct tape, implying that the racers did not have the financial resources to buy new equipment for solely cosmetic reasons. All three foreground riders are wearing the same brand of boot, which suggests that choices in good riding apparel were limited at the time. Another racer’s chest protector lies on top of Chaplin’s front fender. Given that several of the racers are not yet helmeted and otherwise ready, the start of the race must be more than just a few minutes away. Noting that three of the four motorcycles visible are Maicos, the claim that the brand was a common tool of professional racers, even in 1971 to 1972, is reinforced. Other details of period early 1970s dress and fashion are visible on the other figures. The flat, undeveloped background is obviously rural, but we cannot know where. Trees appear to be visible in the extreme background. Other than Tim Hart’s recollections of the persons in the photograph, we do not posses any further historical data with which to compare viewers’ immediate reactions. Gunnar Lindstrom did not recall the photograph being taken. Hart’s girlfriend Julie eventually married another racer, who has since passed away. Gary Chaplin, sponsored at the time by Dennie Moore in Pennsylvania, was not located. Jim Gianatsis, the alleged photographer, did not remember the photograph, although former Dirt Bike editor Rick Sieman believed Gianatsis to be the photographer.[xv] Our remaining questions must remain unanswered for now.

The Motocross Commandos

The third image, the circa 1974 Yamaha advertisement entitled “The Motocross Commandos,” ran in various off-road magazines briefly in 1974. The image is from an original drawing, taken in turn from photographs of Yamaha motocross team members Mike Hartwig, Pierre Karsmakers, and Tim Hart. The drawing has a comic-book quality, probably to enhance its appeal to younger readers. It is black and white. The primary frame in the ad pictures the three Yamaha team riders. Smaller frames picture the trio exercising in a sort of “motocross boot camp” environment, with Karsmakers characterized as a demanding drill instructor. Comments from the three characters are lettered-in, cartoon-style. The advertisement constructs a heroic struggle among the teams of racers, who race for the makers of their motorcycles against one another.[xvi] The struggle (motocross racing) is compared to military conflict, in that the three are “commandos,” elite professionals, united in a joint endeavor, and are undergoing military-type training. In the main frame, Karsmakers, the assigned team captain and trainer in real life, is pictured in the middle; confident and smiling, with arms crossed. The caption reads “Pierre Karsmakers is Pierre Karsmakers,” suggesting that the Dutchman needs no introduction; that he is a famous racer, and we all know it. Michigander Hartwig and Tim Hart cover Karsmakers from either side, slightly heads-down, in deference to Karsmakers, as the text describes their various accolades. The technique of the artist is reminiscent of a number of period and earlier styles. Certainly the overall feel conveys Superhero art, still very popular with young boys through the 1970s, though without the stylized physical exaggeration. The art itself strongly channels Robert L. Ripley. Ripley’s wildly popular “Believe it or Not!” cartoons, published in both daily papers and in book collections in the 1930s and beyond, used a highly realistic, representational black and white art, very similar to “Motocross Commandos.” Millions of Americans who read the cartoons each week in Sunday papers from coast to coast recognized Ripley’s work. Like Ripley, the “Commando” artist used stipple and hatching techniques to create mid-values without modern half-tone printing, and conveys both a sense of drama and a respect for his subjects. And, similar to a Ripley cartoon, the “Commando” art serves to pull the reader in, ready to share titillating information that the reader wants to know.[xvii] The advertisement can also be compared to Bill Mauldin’s Up Front cartoons of the late World War II years. Mauldin’s black and white renderings of his bedraggled infantrymen (primarily the two buddies, Willie and Joe) are less realistically drawn than Ripley’s subjects or our “commandos.” They are, however, engaged in very real combat, where people really are hurt and do die, and where innocents are abused. By combining a cartoon style and conveying the actual mortal consequences of war while posing moral questions, Mauldin created a comic genre with immense acceptance. The acknowledgement of danger in Mauldin’s vignettes is implicit, but this does not preclude humor. Instead, the danger sharpens it. The artist/observer/participant Mauldin served as an enlisted soldier in the Army’s 45th Infantry Division during World War II. His work confronted issues of class as well, often citing the tensions arising from the relationships between officer and enlisted status. In his heart, Mauldin desired a classless citizen-army. In motorcycle racing, the only class lines (if they may even be called that) are those delineations based upon skill and achievement. Here, Mauldin’s soldiers and our “commandos” share a key value: the non-acceptance of social class. For Hart, Karsmakers, and Hartwig, it does not matter that one is from Michigan or from California, or even that another is a foreigner. What matters is that they are all three warriors in the cause of speed, and their successes, not their upbringing or their wealth, constitute their rank in motocross land. Mauldin’s drawings were comics, but his subject was immensely serious; the scenes were humorous, but drew from the realities of war, privation, and suffering. He also illustrated the border between the mythic World War II soldier and the regular GIs who did the fighting. The Yamaha advertisement appeared in 1974, after most United States troops were withdrawn from Vietnam, but with the war very much in memory and the fall of Saigon yet to come in April, 1975. Without conflating riding and war, it is reasonable to note that there was a mythos associated with motorcycles that did not give adequate credit to the people actually doing the (often dangerous) racing—just as we sometimes glance past the suffering and sacrifices of real soldiers. While his artistic style is less realistic, a bit of Mauldin’s inherent believability carries over into the “Commandos” piece. Both artists suggest motifs of struggle. In the end, we want to believe the “Commandos” narrative as much as readers accepted Mauldin’s caricatures as unquestionably truthful.[xviii] We accept the riders’ star status, and look forward to the great potential for each rider, of which the writers assure us. But Hart’s star status in the rough, always-contested arena of motocross was fleeting. After his Maico period, Hart enjoyed three years of Yamaha support. Then, with his knees bad from years of “sticking them in the ground and twisting,” he was no longer able to perform to the company’s expectations. The twenty-six-year-old star and veteran of ten years of professional competition, now over-the-hill racer, was unceremoniously dropped. Hart then went to Canadian manufacturer Can-Am, salvaging partial support, but nothing like the arrangement he had had with Yamaha. Driving around the vast American landscape, racing in the 1976 series, he was once again on his own, paying his way, like in the old Maico days. Hart recalls that he “. . . just wasn’t able to remain competitive with my bad knee. I never did have it worked on. So . . . I quit. I didn’t ride a motorcycle for four or five years after that.” Like fellow Yamaha teammate Mike Hartwig would do when medical problems terminated his riding, Hart walked away from motorcycles entirely for a time.

Retirement

The fraternity of the travelling racers is a fond memory for Hart, and reestablishing relations with them is important to him, now. “I’d travel with those guys hotel-to-hotel, and got to know them all pretty well. We all went to the same places for the series; that’s when Edison Dye started the whole thing here. No one was a problem. Peter Lampuu . . . he was from Finland. I heard he was working for the movie industry, and passed away a few years ago; he was a neat guy and another Montesa rider . . . Tom Rapp . . . Mark Blackwell . . .[xxi] I just attended the Trail Blazer’s Motorcycle Club Banquet. You know, I’ve always been left out of these things! [Laughs] There were so many old friends and heroes there; it was a Who’s Who of motorcycling from the past. Ron Nelson, who first went to Europe with John DeSoto; Preston Petty; Dave Ekins; Stu Peters, who has promoted more motocross races than anyone; Kim Kimbel, who hired me to race Montesa; Sammy Tanner; Gene Romero . . . and many more.[xxii] I had the biggest smile on my face; it was great!” Hart remembers his Maicos as being capable racing machines. “As far as the old Maicos . . . they didn’t need much. They were pretty amazing bikes. The gearboxes might have given us a few problems, but like I said . . . I’d take my bike apart every weekend to make sure it was ready. I certainly did that for all the races in the 1971 series I won. We didn’t do any trick suspension, or trick anything, really. When they figured out how to lay down the shocks, about the year that I switched to Yamaha and the monoshock, that was an amazing thing that no-one had figured out till someone actually did it. Back then, we had six-and-a-half inches on the front and four inches on the back, and we didn’t know any better. But, it worked fine for us.” “That old photograph of me, jumping the square-barrel Maico . . . Well, the hair—that was a Seventies thing. Yamaha made me cut my hair when I started working for them. The full-face helmet, I got that simply because I didn’t want to bust my teeth out. At Ascot one time, I crashed really hard. I had my full-face helmet on, but the cross-brace of the bars went perfectly through the opening. Boy, it just busted my nose up! That was the first time that I ever went out in an ambulance; guess it didn’t save me that much, after all! And, you know . . . everybody crashed a lot back then. Nineteen years old in 1969. Those were the early days; how it began. Nowadays [parents] start them so early, three or four years old. When I was starting, my parents put me in a motocross school; it was taught by Torsten Hallman and Malcolm Smith.[xxiii] It was out in Riverside, California; a two-day school. And, I recall Malcolm taking me off to the side—I was one of the better riders—he took me off to the side and tutored me separately. That was kind of a neat thing. Now, every time I see Malcolm, I ask him if he remembers me! It was in the early days, when I was riding my CZ, my twin-pipe CZ . . . I was able to get together with Torsten Hallman, Malcolm Smith, Roger DeCoster, John DeSoto, and many more great racers a while back. When I got up to speak . . . I thanked Torsten, Joel, Roger and the others who started motocross here. I was so lucky to have been a part of it all.” In looking at Tim Hart’s images and career, we see the arrival of motocross as an amateur sports phenomenon, and the beginnings of professional motocross racing in the United States. Hart’s years in the sport came at a time of discovery; the sport was new, rules of dress were not yet dictated by large clothing manufacturers, and young men around the country could participate with relatively little financial backing. In the next chapter I will examine the career of another young American rider from Ohio, who began racing at the same time Hart stopped. Maico rider Denny Swartz’s career illustrates motocross in the United States for the many young men who grew up in the early 1970s, idealizing the image of the new sport, and who took to the road to pursue that image.If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here. It also just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

What a great story! I remember going to racing with my dad as a kid. It was so fun. Your are right how everything has changed in advertising. It funny we all hate it yet the sex is still there? I remember Tim Hart from that long ago. Takes me back to childhood memories. What do you ride?

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Perfectly written!

Thanks Jordan!

I started with a 92 Yamaha WR200. BEAT THE HELL out of it. Wrecked cotasnntly and bent frame. After about 7 months of aggressive riding, I bought a 09 250 XC-W. This was like heaven. My skills were where I could handle it (once I got used to the throttle). I now have both, but I worship my 250. I am glad I started the way I did, but I would advise a full year on old bike, as I thrashed the KTM still a little bit at the beginning. HAPPY RIDING!

Awsome story, thank you! I grew up racing at that time in NorCal on DKW’s. I remember watching all these guys at Nationals and Trans Am’s. My early hero’s!

Thanks Kevin, I write these articles because of the appreciation of guys like you!

Dave, that was amazing history of Tim you wrote AWSOME JOB!!! Tim and I grew up together in Torrance (Walteria) Ca. ,along with Danny Laporte which is my age.Danny and I rode a lot together when were young(Boy was he fast also) we went though school together and hung out .ButTim,Mike Pera, and I would run down to Torrance beach,then onto the sand,then down to the rocks(end of Torrance beach) and start using rocks as weights,then run back. One heck of one of Tim’s work outs. Just one short story of ONE HELL OF A GREAT PERSON

Hey, Bob–fascinating hearing of your experiences with Tim Hart. Though I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting him in person, he was absolutely the nicest guy to talk to over the phone! As the story indicated, Tim was the celebrity every young teenage boy I knew wanted to be: long-haired, from California, paid to race a Maico. He was quite literally the picture of who we were, in our dreams. Thanks!! Dave (PS–my wife was looking at the classic photo of Tim, Gunnar Lindstrom, and Gary Chaplin while I was interviewing Tim, and couldn’t help but exclaim, “Oh, he’s SO cute!”)

Great piece on Tim Hart. I was that kid – the kid that idolized Hart – I and my two older brothers grew up racing motocross – we rode Sachs and Maico – my dad worked with Preston Petty, he machined the first aluminum molds, and we made the first PP fenders right there in our garage in Simi. Preston was insanely fast and an early hero of mine but Tim Hart – damn he was fun to watch. We raced a few times at Ascot when they ran the Friday night races – Tim would fly through that big sweeper turn – Maico completely laid over, knee dragging, front wheel up and crossed – like a boss – he was the guy I wanted to ride like

Dave–what a great memory that all must be! My friend, Brian Thompson, recently saw a post from PP about some CZ intricacies, and we were of course all passing it around. I’ve been wanting to watch some old MX video of Tim racing…do you know of any?

Sincerely,

Dave

Great write. Thank You.

Mr. Russell,

Your piece on Tim Hart and the early days of MX was so exceptional and incredibly well-written. Tim Hart passed away today and with him passed a piece of all of us who raced during those early years of motocross in Southern California. Thank you for writing this factual, yet poignant article for Tim’s legion of fans and friends to savor and reflect upon in this sad time.

Steve, it must have been incredible to have actually been there, as you were! I hope Tim knew how many people he affected through both his racing exploits and his quiet, graceful, unassuming life.

Most sincerely,

Dave

Thank you for writting such a great article about my cousin Tim Hart. I know he would be so honored. He will be truly missed.

Kelley Cahill

Dear Kelley, It was truly my honor to be able to interview Tim and write the story. I’m amazed at the impact he had on so many of us younger boys at the time. Not that we didn’t think highly of all the other motocross stand-outs, but there was nothing like that LOOK that Tim had–the hair, the helmet, the boots, the Maico (and any other bike he was on). With all the interest, I hope to be able to release the transcriptions of Tim’s interviews–which capture better than I could, his irrepressible youthfulness and excitement about those times. And–he was one of the most pleasant people I’ve ever interviewed.

God bless you, and thank you, again! Dave

He was a cool dude, Lots of hard races with Tim

Pat DeBenedetti

Thanks!

Those were the days.

Yep, Tim Hart definitely helped usher in the golden age of motocross!

Just learning about all of this, I was there ,raced against Tim a few times in those days as I remember it was Tim

And Billy Payne we’re great rivals ,

The bike has all the earmarks of being plummeting; anticipating reconnection with the ground. The rider’s face is covered up, however the watcher takes note of that “TIM” is sewed onto the chest defender he is wearing. He wears massive cowhide jeans and boots. Long hair streams from under the rider’s protective cap, held straight by the slipstream.