No products in the cart.

Uncategorized

The History of Maico Motorcycles and American Sport Motorcycle Culture – Preface, Part 3

The Motorcycle Bug Returns

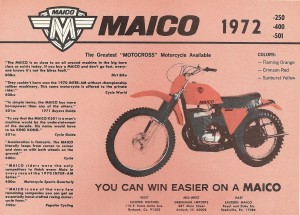

In 1986 I was a twenty-eight year old Marine captain in steamy Jacksonville, North Carolina, preparing to leave the military and get on with life. I was stationed at Marine Corps Air Station New River, across the brackish New River inlet from Camp Lejeune, whose thousands of Marines we supported with our helicopters. Perhaps from too much time thinking about where I had been, or where I might be going next, an idea took hold. I had, over the past few years, enjoyed restoring an old 441cc BSA and a Triumph 750cc triple. Now, I wanted a unique dirt bike. I decided to search for a 501cc Maico. Around the time of its construction, I knew the 501 Maico to be the largest-capacity single-cylinder two-stroke production motorcycle engine ever built. I also knew 1974 to be a special time for dirt bikes, and the pivotal year for motorcycle suspension evolution. I set this year as the target for my as-yet-to-materialize Maico.

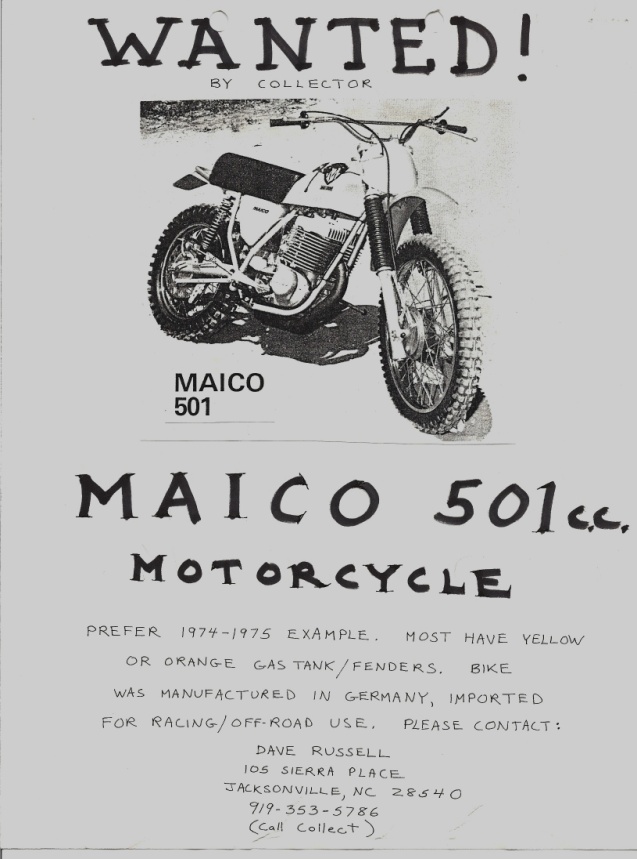

From an old issue of Cycle Guide Magazine, I cut a picture of a 1974 501, produced a crude flier, and copied it. I posted a copy on every Squadron and Group headquarters bulletin board I could find: “Wanted: 1973-74 Maico 501cc Motorcycle.” I waited, without response.

A year or so earlier I had met a part-time motorcycle dealer nick-named Mouse, who also worked as a welder for the Department of Defense, up Highway 17 at the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station. I learned Mouse had been a small Maico dealer years back and he told me of being champion of the sadly now-defunct New River Motocross Track. (“Don’t let’em tell ya otherwise, either!” was his warning. Apparently the title remained disputed after all those years, though no doubt existed with Mouse.) Apart from Mouse, however, I saw precious little interest in dirt bikes, old or new, in the coastal Carolinas at the time. A dealer in Wilmington had a couple old CZs on his lot, but aside from that, the Carolina coast appeared devoid of old motorcycles. The Maico eluded me.

Hemmings Saves the Day

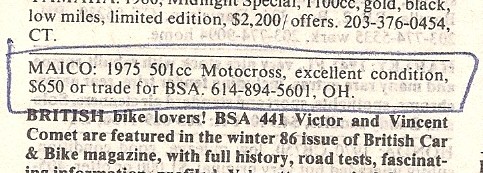

I had nearly given up on the 501, when in the late fall I happened to read the anemic MOTORCYCLES FOR SALE section of Hemmings Motor News. Much to my surprise, I noted the listing of a “1975 501 MAICO” in South Point, Ohio. It apparently was not such a desirable item at the time, for it remained unsold for another month before I could travel from Jacksonville to my in-laws’ home up north in Washington, Pennsylvania, to retrieve it. Once there I borrowed a pick-up and made the six-hour drive down through West Virginia to the extreme southern tip of Ohio, where sat South Point and my dream Maico.

Before finalizing the deal, I recall sitting at my mother-in-law’s kitchen table, haggling with the seller, who I would come to know as Jeff Willis, a restorer of some renown of early American motorcycles. The $650 asking price seemed excessive, this being 1986 and a 1975 Maico at that time little more than a mildly-interesting, wildly out-dated old dirt bike. I thought such a machine should bring no more than $400. After coming very close to forgetting the entire affair on principle, I managed to get Willis to agree, over the phone, to a meet-in-the-middle price of $525—only if, I stressed, it ran.

By nightfall the next day I was clanking through the arm-stretching manual four-speed transmission and pointing the heavy-duty old F-250 snow-plow truck back north from South Point, Ohio. Towards southwestern Pennsylvania I went, now proudly displaying in the truck bed a well-used, flat-tired (and non-running) old German motorcycle. The yellow fiberglass tank with the “M” shield decals peeked at me in the rearview mirror. I was a Maico owner at long last. I wondered if the West Virginian pedestrians, plodding face-down through the snow and greying slush, had even the vaguest realization how exotic and transformative the machine in the back of this truck was. I did, I reminded myself, and it felt good.

The Rebirth of a Maico

The 501 sat for a decade before undergoing the restoration process, joined in its basement parking soon after by the slightly younger 250 Maico, a duct-tape-cocooned 247 Montesa, and the home-turf camaraderie of my faithful and better-dressed first bikes: a 1971 Kawasaki G3TR-A and 1974 KX125. Although career changes and family obligations kept me from delving into the restoration for years, I did make frequent visits to the 501’s basement home to admire the machine’s functional beauty and construction, and to imagine its history in the coal hills of West Virginia. I enjoyed gazing at its perplexing squared-off gas tank, marveling at how the flat panels joined together to achieve the form. I wondered why anyone would attempt such an unusual design in the first place, being surrounded then by the convention of rounded and more easily molded “jelly-bean” style of automotive bodywork. I absorbed its aesthetics; the beautiful ways in which the air-box echoed the lines of the rear frame loops; the sculpted shapes of the fenders, interspersing curvature with abrupt horizontal line; and the Prussian severity of the flying “M” tank emblems—all reminiscent of some medieval military coat-of-arms. And that engine, with its huge cooling fins bulging out and visible on either side of the narrow little yellow gas tank when looking down from the saddle; the traces of hammer marks on the head from some detached German factory worker; the contoured, crudely-finished cases holding the mysterious motor-innards which produced the legendary power. I had never heard the words “material culture,” and did not realize that what I was doing actually had a name. I was interpreting an object. I was analyzing it, studying it, and learning from it . . . though to others I was just staring at an old and broken motorcycle.

The gas tank on the Maico particularly fascinated me, and at first appeared to be a perfect example of “form following function.”[1] The tank certainly was narrow, and its shape allowed a low center-of-gravity; both positive qualities for a motorcycle. Or, was the unusual form dictated by cost, wherein the squared gas tank and course engine castings were simply cheaper to manufacture, for reasons relating to materials or assembly time? Another possible reason for the shape could have been (as American Studies scholar Jeffrey Meikle suggests of the American motor car), that since its function was to be sold, the object’s appearance could in fact be “following function” if the distinctive aesthetic design helped it sell.[2] Were the Maico’s war-like looks only a marketing tool? In any case, I marveled at and enjoyed the Maico’s appearance. Perhaps it is true that the wealthy collect fine art, while men of more modest means are left to admire their motor vehicles.

Years later I would again ride restored Maicos, the first time since trading-off my Kawasaki to a high-school friend, one afternoon back in 1975. Running a few laps on his homemade motocross track around a Pennsylvania farmer’s corn field, I had experienced the long-travel, painfully-slow-revving but wondrous handling of his little Maico 125. Many years later, it was rewarding to ride a variety of Maicos, as well as other premier off-road motorcylces, a generation after we young boys dreamed of such an extravagance.

For the past thirty years I have restored and collected Maicos, and, more recently, have begun to learn the history of the irascible, ultimately self-destructive little company that made them. Given their reputation of producing the finest off-road motorcycles in the 1970s, beginning the modern long-travel-suspension era, and creating the 1981 MC490 (a motorcycle many would consider the single best motocross bike, for its time, ever made), I remain astounded at what little written information on Maico is available.[3] Among younger motorcycle enthusiasts, the Maico is recognized only sporadically, and in a folkloric manner, relating to its alleged power and speed and old racers they know who had one, “back in the day.” This lends the Maico’s story a certain ongoing power, as it resides in the border between memory and myth. And the myth deserves a forthright explication.

Throughout my research I was impressed to discover unexpected connections among the many individuals I contacted. Recalling Michael Kammen, I found my own “mystic chord of memory” binding together the old Maico community, even today. This connecting web may not appear unusual when considering any other activity involving a group of intimate, like-minded characters. But when applied to an era and a culture spread across continents, I found it significant. For example, [parts maker] Greg Smith grew up with [racer] Tim Hart; who is lined up on the starting gate in a famous photo with [editor and racer] Gunnar Lindstrom; who of course knows fellow Swede [and champion racer] Ake Jonsson; who spent time with [engineer and Maico employee] Selvaraj Narayana; who remembers giving a particular motorcycle to [sponsored rider] Denny Swartz, and who fixed [local racer] Brian Thompson’s transmission at [importer] Dennie Moore’s; whose first or second dealer franchisee was Gig Hamilton; and so forth. This cross-continental familiarity amongst cultural members was surprising. I was entertained at every turn to find an uncanny, “Yes, I knew him!” connection with the other participants in this unique brotherhood, spread across time and space. In all cases, these men respected one another. This is not to say that they always agreed with each other, however, with respect to their past relationships or (most significantly) the events leading to and following Maico’s failure.

Maico’s decent into bankruptcy in the years leading up to 1983 carried with it considerable financial hardship and personal tragedy for several of the contributors to this work, and some retain strong feelings and divergent points of view on this subject. Maico’s story is more complex and controversial than a simple nostalgic recollection. Not all the contributors agree about several key assertions made by one another, and their narratives do not all conveniently align. (One allegation is so strong that it was deleted at the speaker’s request, for fear of retaliation from a former Maico employee in Germany.) I have included these sometimes-disagreeing first person statements, along with my impressions, but the reader can make his or her own judgments. In comparison to the rich story of Maico’s successes, I believe that the latter years of Maico’s collapse are, while essential to understand, ultimately less important. Of course, for businessmen who lost money, the company’s failure remains bitter. In any case, had the Maico company survived and not disappeared in the circumstances that it did, the mythic power of the machine would not be what it is, today.

This work places the Maico within the context of 1960s and 1970s culture in the United States. For some, this will refresh old memories. For scholars of American society during the late twentieth century, it will hopefully convey something of the culture of racing and riding in the glory years of the dirt bike in America, and describe the men who rode and gathered it. And, for those to whom motorcycling remains foreign territory, this dissertation will explain how much it all meant to so many people, and hopefully complete a small bit of the historical narrative of this period in United States history. Once, there was Maico, and the word carried meaning.

Riding versus racing

Throughout this dissertation, I refer to the action of operating a dirt bike as both riding and racing. Racing is of course also riding, but is further used to communicate riding in a context of formal competition. The Maico was designed as primarily a racing motorcycle.[4] While Maico off-road motorcycles could be simply ridden off-road and not formally raced, the machine was very much designed and marketed for the latter use. To ride and not compete with a Maico was entirely reasonable and not unheard of; but, considering the relative cost and the required maintenance and upkeep demands, this would be tantamount to purchasing a Porsche to deliver the mail. This “thoroughbred” quality is part of what helped to make the Maico an icon. Foremost, it was a racing machine; the decals on the gas tank, the identification plate on the steering head, and the first pages of the owner’s manuals proclaimed as much. Maico’s self-identification as a racing-specific tool meant that it was intended to be the right bike for serious racers. Thus, the Maico enthusiasts interviewed and contributing to this book are all doing so from mostly a racing perspective; motocross, for the most part.

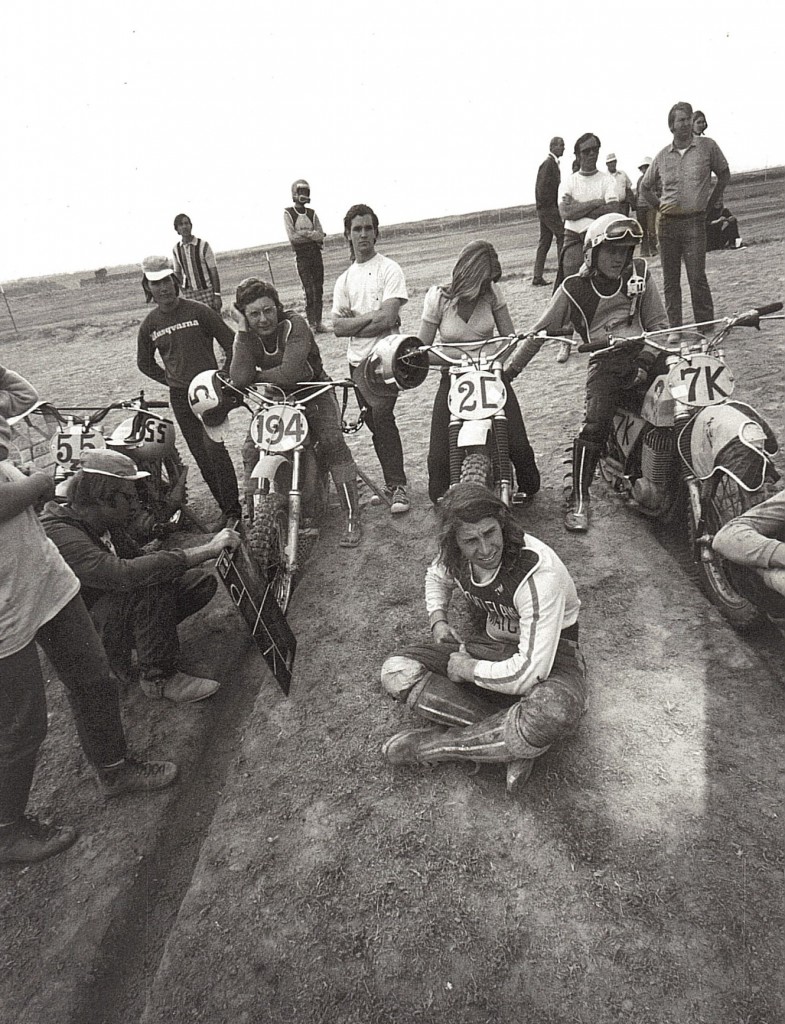

Motocross, the Maico’s primary application in the 1970s (although scrambles and flat-track saw significant Maico participation) is defined as an outdoor competition over a closed-circuit course of natural terrain features, usually less than two miles, and with the ultimate score being the resultant of numerical finishes in two heat races, or motos. Moving to this level of commitment to organized racing indicates a person who differs in significant ways from those of us who, for example, were content to trail-ride or were unable or not interested in organized competition. Motocross racing was expensive (I estimated the costs to be about $70 a week in 1974) and competition past the high school years often implied a conscious choice of selecting racing over college (or other career choices). These young men made deliberate decisions, sometimes with considerable costs, in order to race.

Boys who loved to go fast

When considering these men (there were very few women; off-road motorsports in the latter part of the twentieth century was predominantly a male domain and continues to be a gendered environment), let us consider several statements of fact. First, motorcycle racing in the late 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s was not an especially viable career path or profession from which these boys and men could realistically hope to extract a life-long living wage (given the very few paid professionals and their short racing careers). Granted, most of them dreamed of racing professionally at one time or another (much like a little-league baseball player imagines playing in the pros), and a many actually enjoyed some form of “sponsorship” by a local shop, which helped to enable their racing. While a minority, however, did contemplate the possibility of earning any sort of substantive living during their prime wage-earning years as a motorcycle racer, most did not. Hence most of these men were knowingly devoting a lengthy portion of their lives to passion they knew would probably not “pay off” in any way in the future, and would in fact cost them.

Next, motorcycle racing in nearly all its forms is still very much an activity embraced by a blue-collar to middle-class socio-economic group, with a common culture, background, and value system. The demands of racing caused participants to be diverted from some professions requiring higher education, possibly from high school sports and other school activities, and also (possibly) from traditional religious services. In the United States of the 1960s and 1970s, prevailing social norms meant that a large percentage of individuals generally attended religious services on Sunday: the day most motorcycle races were and are still held. With Saturday often being a “travel” day, even Saturday worshippers would have had problems. Thus, a boy beginning racing would, very generally speaking, be a young person given substantial personal freedom and not required to attend church by his family. Also, the family’s tolerance of the potential danger awaiting their child, entirely foreseeable in a competitive motorsport, is worth consideration; not every teenager is permitted to engage in a “dangerous” sport. Indeed there is a paradox apparent to the outsider: before most young people can even legally drive (age sixteen), these young teen racers were allowed to operate motor vehicles in a racing environment. Anecdotally, motor racing (and other potentially dangerous activities such as hunting) appear to be more accepted in non-elite socio-economic familial conditions.

Finally, a boy and his family may have had to negotiate the negative connotations of the motorcycle image itself—even though riding a dirt bike shares nothing beyond two wheels and a motor with actual outlaw/socially-deviant biking culture—which had certainly permeated much opinion in the United States by the 1960s. Of course, for families already acclimated to motorcycling, this was no big deal. However, a young boy, new to motorcycle racing culture and from a non-motorcycling family, could expect concerned (but uninformed) adults to associate his riding with that of lawless men who wore black leather and appeared threatening. This was the dominant motorcycle image of motorcycling, although it had nothing to do with off-road riding or weekend racing.

A Generation Grows Older

As these young men grew older, and if they wanted to continue racing, they often sought work as mechanics (a profession with obvious advantages) to facilitate their sport. Racers also tended to be in the trades, since their prime racing years were exactly those when college and training for a profession would have occurred. Many serious racers then and now had families who operated motorcycle dealerships, with, again, clear benefits.[5]

They sacrificed and made these decisions because they loved the sport and could not allow themselves to not do it. They made a choice to pursue racing in spite of the costs, at least until injury, family responsibilities, or funding caught up with them. Motorcycle racing in general was (and is, even while being the cheapest and most popular of the motor-sports) expensive, modestly dangerous, and tended to keep one from other social activities. These men recognized there would be a cost, but pursued their passion none the less, while they could.

A number of the men whose stories are found in the articles to come did make the jump and successfully constructed careers in motorcycling. Others left motorcycling and followed different careers. Either way, for those of us who also loved motorcycles, we desire to know the rest of their stories. We, who sometimes wonder what would have happened if we also had stepped out and taken the chance that they did— but instead rode at the local racetracks, around little towns, and on strip mines across the United States—need to know how it worked out for them. They were us, before we drifted away.

In later decades, professional career racing would become feasible for a great many more young men. As sponsors attached themselves to the excitement of motorcycle racing, the sport became lucrative for young men in ways it never was for most riders in the 1970s. Denny Swartz illustrated this change when he tracked down the campsite of a young national AMA #31 racer (the double-digit AMA #31 signifying the rider is at a minimum one of the top 100 pro-level motocross riders in the county at the time), decades after he himself carried that same number as a Maico factory-sponsored rider. Rather than an old cargo van like Swartz nursed around the United States, a $500,000 RV rests at the new #31 rider’s campsite.[6]

While few of the rest of us achieved in motorcycling what these men did, whether they were highly paid for it or not, we at least knew enough to admire them for it. We felt that same passion, too. After all, they were like us; just faster.

These writings provides an in-depth artifact analysis of the Maico motorcycle and also illustrates the American off-road culture at its pinnacle. While I feel it is necessary to include technical and cultural details, I have tried to balance the technical with the subjective. This combination will hopefully offer the reader or scholar the best opportunity to view this overlooked motorcycling community. In the end, I hope this text is at once enjoyable, informative, and stimulating to readers. For some, I hope that it causes us to look beyond that rough old motorcycle moldering in the shed or basement, and perhaps understand more of the complex and changing period in United States history in which it once operated. Perhaps that old motorcycle carries a message for us. Or, for others, a window might be found into the nature of that father, brother, or boy-down-the-street, who we all admired in some way, because they raced motorcycles. Optimistically, this article and many to come will fill some of the void which presently exists in the history of this unique motorcycle, of the competition culture in the United States with which it intertwined, and of its role in rehabilitating the German image in post-World War II American consciousness. It begins with a careful look at an old motorcycle. As James Deetz noted of the opportunity for discovery that an old object affords us:

“If we could in some way find a way to understand

the significance of artifacts as they were thought of and used by Americans in the past,

we might gain new insight into the history of our nation.

[Things] carry messages from their makers and users.

It is the archaeologist’s task to decode these messages,

and apply them to our understanding of the human experience.” [7]

[1] Lous H. Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” Lippincott’s Magazine 57 (March, 1896), 403-9; and later published as “Form and Function Artistically Considered” in The Craftsman 8 (July, 1905), 453-8.

[2] Jeffrey L. Meikle, Twentieth Century Limited: Industrial Design in America, 1925-1939 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979), 11-13.

[3] Rick Sieman, “What Killed Maico?” Reprinted as “Maico Stories” at VMX Unlimited, www.vmxunlimited.com/pages/Maico-Stories.html, Accessed March 8, 2014. Sieman affirms Maico’s elite status in the 1970s, as well as the superiority of the 1981 MC490.

[4] Maicos were also used in enduro competition. Enduro, given its generally slower speeds over time routes, is usually referred to as “competition,” rather than “racing.” The same could be said for observed trials.

[5] Among racers who also were a part of family dealerships mentioned in this dissertation are: Gig Hamilton, Dennie Moore, Bond Way, and the Sidle family.

[6]Interview with Denny Swartz by David Russell, January 16, 2009, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[7] Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1996), 4.

first off, your site is AWESOME, keep with it. I never have even heard of Maico until today! All I know is about the more commercially seen brands today like harleys and Yamahas. So is this something you can ride on the road too or only in the dirt? obviously I don’t know too much lol

TheDopestMatrix

The Maico was essentially a competition-only bike. They DID venture into street bikes (to the despair of some managers) and were thoroughly outdone by the multi-cylinder, clock-work perfect Japanese machines. But…the off-road bikes were thoroughbreds! If you get a chance, hang in there till the final chapters of the Maico dissertation–they examine these business decisions! v/r, Dave

Can you plz call me I would love to talk with you I would like to try to find the owner of maico bikes 5705418245 i would like to try to make them again

Walter, check out the Maico facebook group. You’ll find all kinds of great Maico info, including bikes for sale!

Hi and thanks for your great article. Vintage motorcycles have always been a passion of mine and its amazing to hear from a like- minded person.

I’m especially impressed with all the info you have on maico. I’ve been able to learn quite a lot myself.

Thanks again and keep up the good work.

Hey, M–thanks. The vintage bikes can be a lot of innocent fun; fills our aesthetic needs and desire to take things apart at the same time! Dave

Your story intrigued me greatly i loved hearing about your early experiences with motorcycles

my brother recently bought a old bike that he enjoys riding greatly

I myself my consider getting one in the future as well

I was wandering what kind of bikes you would recommend to someone who is just starting out with motorcycles

I’d recommend a late-model anything, that RUNS, if you plan to ride. The nice thing about advances in technology is that modern motorcycles–like cars–are very well-made. No more leaks, early breakages, etc., for the most part. (Of course the downside to this is that–again, just like cars–it becomes hard to self-maintain the vehicle, and a “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” experience is pretty much history. (I can’t even change the tire on my modern Triumph, if it should need it, along the road, as it has no center-stand!) I’d also highly recommend riding (and falling-off) a small dirt bike, before venturing into a heavy, powerful street bike. Personally, skills I learned on little dirt bikes have kept me safe on larger street bikes, many times over. Have fun and be safe!

Do you have any info on what it was like in the factory during the good times? It would be awesome to hear about those days from the engineers standpoint! Great article, thank you!

Hey, Chris–YES, I was able to get a picture of life at the factory in the good times, through the kind interviews with several Maico company leaders. We’ll have those out in coming months. (And…since both my interviewees were engineers, their memories are very much flavored with Maico’s engineering triumphs. One was the idea of the 36mm OD fork tubes, that–without increasing wall thickness–resulted in much more rigid forks than the then-usual 35mm units, used by everyone else. Funny how much difference a millimeter made!)

Dave

Very useful information

Dave, this hits on so many memories, exactly like you’ve described. I call Northeast Illinois home, began racing in the spring of 1971 on an SL 100 Honda, was sponsored on an SL 125 by the local shop and then bought my first 250 Maico that fall. Was a glorious way to spend my time and money, and to enjoy it with so many people that I still consider good friends. Your comment on the overlooked segment of society and specifically motocross was further documented in “The Art of Moto” by Mark Homan. He was the little brother to a girl I was dating in 73 and is now based in the Los Angeles area, working in film making. Helped him with his bikes and getting to/from the races, stayed friends after the relationship ended. He had a “premier night” at the local movie theater and it was literally standing room only. It was easy to tell the guys who used to race, we were all leaning ahead in our seats and concentrating on the screen during a start scene. It’s a wonderful group of people to be associated with.