No products in the cart.

Part 2: Harley-Davidson enters my life

Harley Davidson were having problems marketing their entry into motocross during the late 70’s. They produced a 250 two-stroke, designated the MX250. This was Italian, designed by Aermacchi. The project started well, winning the 1975 Baja 500, and having the most powerful engine (barring the Can Am 250) of that time. It was, however, expensive, heavy and difficult to ride, and wasn’t selling well. Harley-Davidson felt that it would be a good idea to see if the motor could be used in other branches of motorbike sport, to offset poor sales in motocross.

Jon on the initial effort, powered by a tuned SS250 engine, 1979. (Photo: the author)

I was approached in 1978 and asked whether I’d like to try one of these engines in grass track racing. My eldest brother happened to be in charge of motorcycle engine design for an international engineering consultancy. They had a tie-up with HD involving the big V-twins (Note: This is probably sacrilege, but I remember at that time being distinctly unimpressed with HD engineering, when I saw the effects of a few hours spent on a rolling road, causing exhausts and oil tanks to fall off and frames fracture!). He spent some time in Varesse, Italy, in discussions, and the requirement to find other uses for the MX250 engine was raised. My services were volunteered! As I recall, the SX 175/250 and SS 175/250 motorbikes were sold in the UK either badged as HD or Cagiva, but as far as I know I have the only MX250 variant in the UK. The conventional big-bore Harleys had a big following in across Europe then, as they do now. All the parts I required were provided free, although I had to pay import duty on some. They were either imported via the engineering consultants, a UK HD dealer, or AMF International, Ltd. There was surprisingly little follow up from the factory; I think they had probably already given up on continuing manufacture of the bikes and just wanted rid of parts—although they did send me a set of close ratio gears in about 1981. HD was apparently still working on the bike, even then, to try and make the engine more manageable.

The prototype MX250 goes into the initial chassis, later in 1979. (Photo: the author)

My two elder brothers had made a name for themselves designing and constructing left-hand grass track sidecar outfits in the 70s, prior to making road race outfits in the 80s. I’d started racing in 1972 (aged 16) driving a 850cc Saab three-cylinder, two-stroke-engined sidecar outfit: a hand-me-down from my elder brother. The use of this had been conditional on my spending the previous year tied to the workshop/lathe, producing bearing housings, spindles and intricate tube shapes for the outfits my brothers engineered. (Until very recently my brother owned a company designing and manufacturing motorcycle gear boxes, both for classic bikes and current FIM world superbikes. I don’t know if classic bikes are raced in the States, but if they are and gear ratio changes are allowed, then this factory can provide them! https://novaracing.co.uk/)

The hand-me-down, Saab-powered sidecar outfit. Note double back wheel to try and get grip from the two-stroke’s smooth power output. This was first raced in 1967 by my brother, with input from Saab. Designed and manufactured by us; clean, rugged construction. (Photo: the author)

I changed to racing solo machines in 1974, finding that the costs of racing a sidecar outfit (whilst attending college)–plus the rapid turnover of passengers—too constricting. The solo was yet another hand-me-down from my brother, who had by then fancied his chances as a speedway rider. It was an Elstar 500cc (BSA powered) which he used a couple of times, before he decided solos weren’t for him! I’d never ridden a solo grass track bike before, but filled with youthful enthusiasm I entered an event with both the sidecar and solo. Having only had about 10 minutes practice in a friend’s small paddock, when called out for official practice at the meeting, I couldn’t even get it to start! Luckily, a fellow rider obliged and helped me. My excursion into racing a solo produced much interest from my fellow sidecar competitors, with bets being taken as to when I would fall off. The answer was every sodding corner!

1974: First solo race, first corner—but not last time of kissing dirt! BSA 440cc (Photo: the author)

Initially Harley-Davidson supplied only the engine, a bastardized experimental SS250 (street-trail) version. This had been used to test different gear systems to make the power more useable and as such had a Perspex see-through inspection cover fitted, to allow visual inspection of the gearbox. Both engine crankcases are stamped RE3 (Research Engine 3?). It was fitted into a Ford-Dunn frame that had previously housed a BSA 441 Victor motor, modified to 500cc with a B50 head fitted, and running on methanol. Using this test sled with the Harley engine, it was soon apparent as to its flaws. The engine was so vicious, letting it come off the pipe and then its subsequent return to the rev range, that it could certainly be described as “interesting”.

Just to show the calibre of riders which I was up against: here’s multiple Long Track World Champion, and World Speedway runner-up Simon Wigg at one of my races. (Photo: the author)

HD were impressed enough by photos taken whilst practicing, that they offered to supply any parts we required from the MX. They provided different gear ratios to try and make the power-band more useable, but with the gear change being on the left hand side and unreachable whilst cornering (left turns), staying on the pipe was extremely challenging. A handle-bar-mounted gear change was tried, which allowed for just Up changes in preparation for exiting the corner. Unfortunately, the power surge was so fierce that after a couple of times being high-sided, this idea was abandoned.

Raced in the above mode gave pretty poor results, and it was decided to change tack. The 250cc class in the late 70s was still dominated by 250 BSA four-stroke engines running on methanol, augmented by a sprinkling of new generation two-stroke machines powered by Bultaco and Montesa engines, etc. Unlike 500cc bikes, none of these 250s seemed to have the power to sustain a full corner drift; there appeared to be a fair bit of “paddling” involved to get round corners. Also, about now, some of the moto cross guys started turning up at grass track meetings in the Southeastern centre UK with Suzuki RM250s and Kawasaki KXs, which were embarrassingly more than a match for our traditional grass bikes. They also adopted a different riding strategy: flat out up the straights, ride the corners, then flat out again. I thought a bike utilizing the best bits of both types would be the way to go.

The result was my next Harley-engined bike. It was very light at 88.5kg (195lbs, ready to race), with a large MX rear wheel; plus brakes front and rear and essentially grass track front end and steering geometry with less suspension than a MX bike. Did it work? No! If the MX tyre (I’ve since found that the tyre provided by HD was notorious for its very poor characteristics) lost traction going into a corner it would “float” and instead of going round the corner would continue in a straight line—rather off-putting!

The final HD grass tracker. As this engine is an experimental prototype, it does not have the separate production ignition cover on the left. OEM MX250 rear wheel and tire (Cheng-Shin!), Girling shocks, Suzuki silencer, early Honda CB125 forks. The frame was fabricated by the Ford-Dunns. (Photos: the author)

At this time I was also racing a 500cc Weslake four-stroke Long Track racer, competing in the Expert, Grade A category. Riding this quirky 250c two-stroke wasn’t doing my 500cc racing any favours, and after yet another frightening outing it was put in the back of the garage and forgotten, in about September 1981. I don’t have any photos of the Harley in action in its last version as my father, a keen photographer, took most of photos I have, but he sadly died before this bike was built. I’m sure photos were taken by press photographers but it was before the days where the desire to document every second of one’s life was the norm.

The 500cc Weslake in action, 1980 (left) and 1983 (right). (Shades of Evil Knievel in those leathers?—Editor) (Photos: the author)

Early this year I needed to cut some long grass and remembered I had a large four-stroke Flymo (brand of lawnmower in the UK –Editor) mower in the garage, which had last been run 12 years previously. To my amazement–along with a bit of encouragement–it started. Previously, during COVID, I’d also started on a bit of a garage clear-out, and had got rid of a couple of old speedway machines that I’d always meant to do up. This meant that the last of my racing motorcycles–the little Harley Davidson MX250 engined grass track bike—now appeared at the front. Mindful of my success getting the Flymo to work after so long, I had a burst of enthusiasm for getting the 250 started. After filling the cylinder with GT85, followed by oil, I managed to free the piston (chromed bore). Then I managed to get a spark. The clutch remained seized. The carb was still full of a dangerously luminous, green-looking fluid. So, I stripped the carb; carb cleaner just wouldn’t touch the manky deposits, but petrol worked much better. All the jets were badly blocked, but using brass wire I got them clear. The fuel tank, which is the frame top tube, was luckily dry and fairly rust-free.

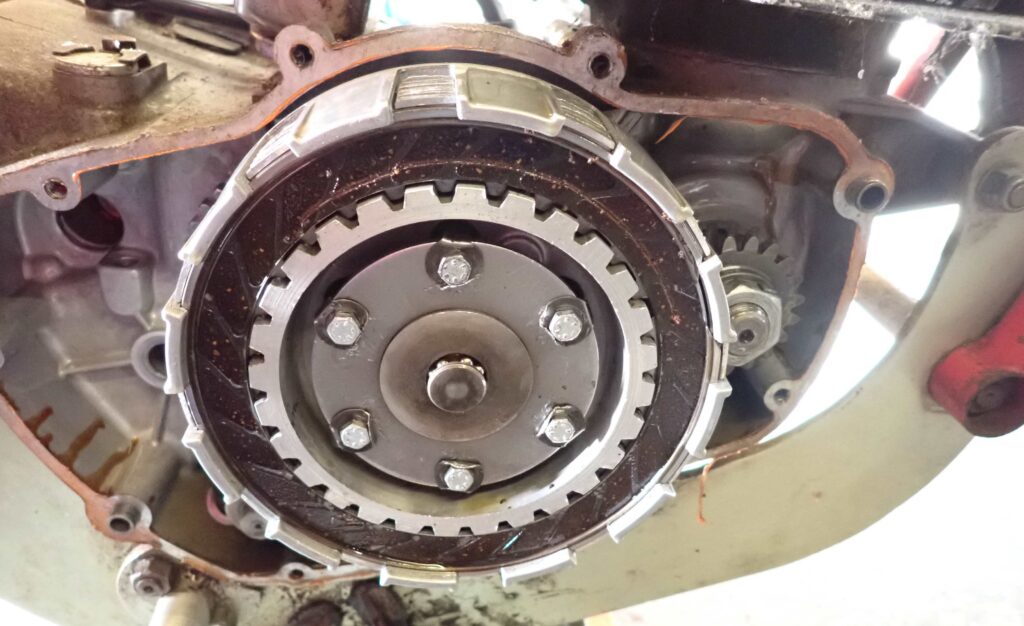

Left: stock Harley rear wheel assembly. Right: Perspex (clear acrylic, trademarked in the UK) inspection cover for the prototype MX250 gearbox. (Photos: the author)

Fueled it up, and after a few kicks it burst into life! Since then, I’ve rebuilt the clutch and had the carb ultra-sonically cleaned. Otherwise I’ve left it in the state it had degenerated too, complete with mud from its last race!

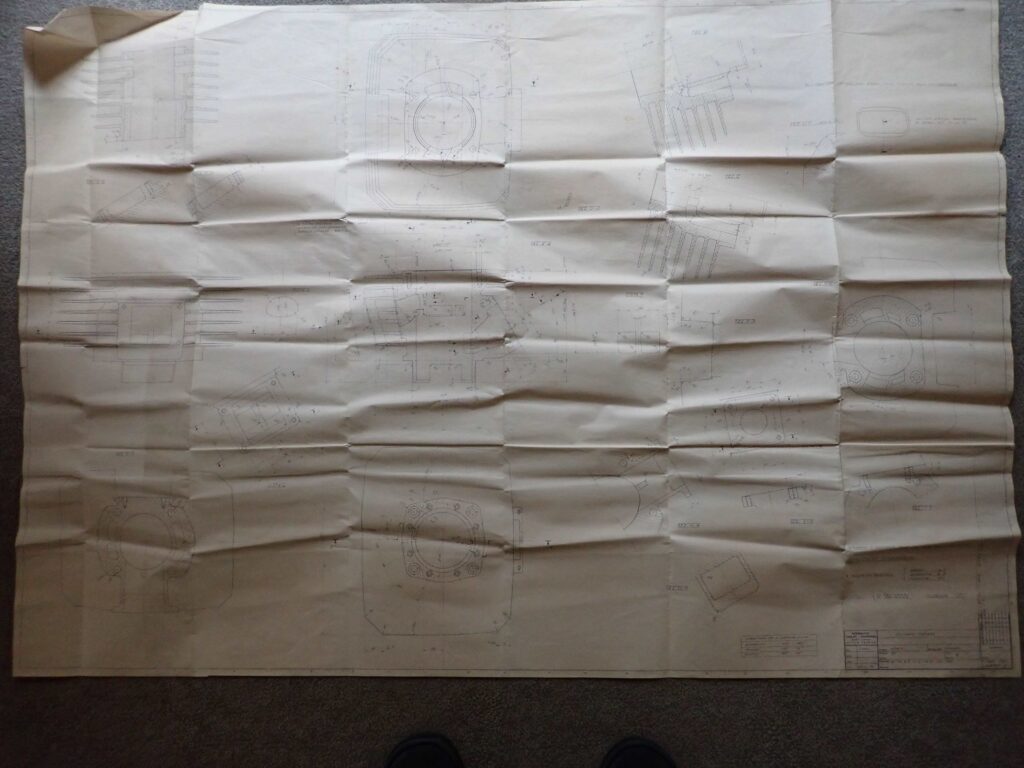

The factory drawings I have show that the MX barrel was designed in 1973. The general arrangement drawings were produced in 1975. As far as I can tell, the engine (apart from the barrel, head and carb) was identical to that in the SS250 road bike, but sprayed black and with the tachometer drive omitted and blanked off.

MX 250 engine drawing furnished to Jon by Harley-Davidson. (Photo: the author)

MX250 prototype clutch. (Photo: the author)

I retired from grass track in 1983 after 11 seasons of throwing myself at the ground, mainly due to fear and a new romance, and moved on to building and flying aircraft.

I’ve no idea what to do with the bike, I imagine that engine spares have become rare, so I wouldn’t like to run it too much. We all get to that point in life when you just have to de-clutter; I’ve had too many interests, which have all necessitated copious amounts of gear being purchased.

Jon Ford-Dunn

Editor’s note: Jon does indeed have many interests! Among them are: triathlons, building and flying his own airplanes, fishing, and travel.

Addendum: the components used in the Harley 250 grass tracker:

Harley Davidson MX250 experimental engine with Perspex gear inspection window.

Del Orto 38mm PHM Carb with K & N filter

Harley Davidson MX250 exhaust system, fitted with Suzuki RM250 silencer

Harley Davidson MX250 right and left footrests, plus brake and gear change

Harley Davidson MX250 rear wheel, complete with brake stay

Harley Davidson MX250 original OEM tyre (Cheng Shin 4.00/4.5 -18)

Chain tensioner (HD?)

Girling gas shock absorbers

Honda CB125 (1970’s) modified front forks

Renthal handlebars

Front wheel hub (Hagon?)

Seat (Hagon?)

Front & rear mudguards (Beamish Suzuki)

Ignition coil (Lucas Powercoil 6v)

Frame & Swinging Arm (Ford-Dunn)

Tommaselli HPS throttle

Tommaselli control levers

Throttle cut off

Weight (wet) 195.75lbs (88.5kg)