No products in the cart.

Early Motocross, Maico

Early Maicos in the United States

While it could be argued from several standpoints, we can say with reasonable evidence that Maico produced the first two-stroke, purpose-built dirt bikes to reach North America. They didn’t come in great quantities at first, may have had lights installed, and didn’t (at least in the mid-1950s) resemble our modern idea of an off-road motorcycle, but they were indeed machines bred for dual-purpose use. And, due to Maico’s experience producing motorcycles for the German Army, the bikes not only appeared to be rugged and dirt-worthy, but certainly were. Maico did much to perfect expansion chamber design (not to take anything away from East German MZ), and built a strong, tune-able, lightweight, and easily modified machine–one built by enthusiasts for enthusiasts. Here is the story of these machines.

Maico and Motorcycle Innovation

To comprehend another culture, an understanding of the material objects central to that culture may be required. Just as a student of surf culture should thoroughly understand the physics of the surf board and surfing, or the student of early American life possess a command of colonial housing and barn construction, anyone examining motorcycling culture must understand the motorcycle. American Studies scholar John Kasson recognizes that Americans, in particular, have always had a special connection with technology, and much can be learned about them through analysis of their industrial objects.[1] In the case of motorcycle culture, this analysis of an industrial object is necessary if we are to understand and decode both the language and the motivation of the motorcyclist. The motorcyclist’s language and his desires are inextricably linked to the technology of motorcycle power and speed. This technology is critical in the case of the motorcyclist, as technology is the catalyst through which the rider is enabled to realize his or her aspirations of performance.

The story and some details of the early model Maicos in America—that period from roughly 1955 to 1970—will equip the reader with a reasonable knowledge of motorcycle design and will set a foundation for the understanding of important technological innovations affected by Maico and Maico riders, presented in later chapters. This chapter will also introduce the critical split in the evolution of the motorcycle from the early general-purpose motorized two-wheeler to the more singularly-purposed modern motorcycle; specifically, the creation of the off-road motorcycle. Finally, this chapter and the associated pictures will serve to introduce the common language and shared references which allow us to understand how the American off-road motorcycle community—often opaque to outsiders— defines itself.

This technical history owes much to Jim McCabe, an early Maico enthusiast originally from Markle, Indiana, who raced motorcycles in a variety of events in the American Midwest from the mid-1950 through the 1970s.[2] Before his death in December, 2009, McCabe was recognized as a pre-eminent authority on not only Maicos, but on late-1900s North American motorcycle racing. McCabe was a largely self-taught engineer, and possessed an amazing degree of mechanical prowess. His level of interest and understanding of mechanical objects was reminiscent of the generations of American males before the 1980s, when mechanical knowledge was an indicator of manhood in American culture. Jim McCabe was that typical young American male, smitten by the power and thrill of motorcycles, when the unusual German Maicos first appeared in the United States.

In the Beginning…

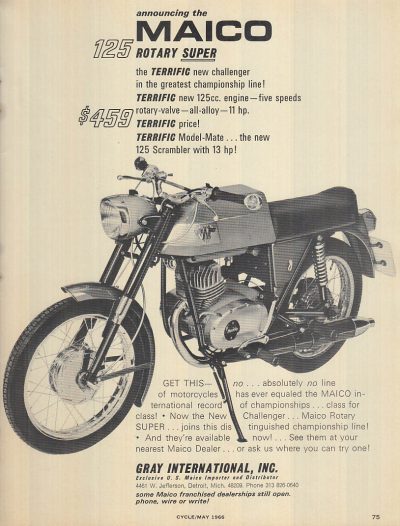

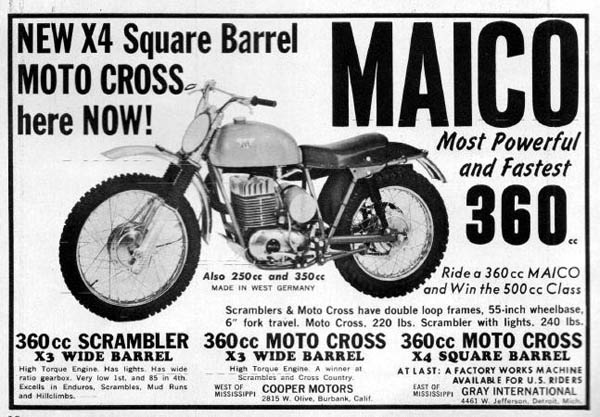

The Whizzer International Corporation, based in Pontiac, Michigan, first imported and distributed Maico motorcycles in America. Whizzer International was also the distributor of the Whizzer motorized bicycle, which was very popular in 1940s and 1950s America. At this time, Michigan was at the epicenter of world motor culture. Whizzer, owned by the Gray brothers, first imported Maicos in 1955, and initially sold directly to buyers while they worked to establish a dealer network for the new product. In 1958 Nick Gray left Whizzer to found his own importing and distributing company in Detroit, Gray International, and took the Maico brand with him. The Grays functioned as the Midwestern Maico importers through these years, and also dealt with other brands and products.

The early imported Maicos were 250cc and 175cc four-speed “Scrambler” (implying they were built for racing) models with close-ration gearboxes and Earles forks.[3] Being specifically designed for competition, these models had immediate appeal to performance-oriented American motor enthusiasts. The cast-iron cylinders on the Scrambler were ported for maximum power output, and the peppy, lightweight machine stood in great contrast to the much heavier British and American motorcycles of the period.

The other road riding and Enduro models were available with more sedate power-output characteristics, sharing the same basic frame design, seats, and gas tanks. Maico Scramblers apparently gained popularity very quickly in the Midwest; Jim McCabe recalled being on the start line of eight-bike Ohio heat races as early as 1956, with four of the motorcycles being Maicos.[4] This recollection is evidence of the immediacy of Maico’s penetration of racing culture. The 250 Maico Scramblers claimed horsepower ratings of around 18 horsepower—impressive for a 250 cc motorcycle of the time—and were capable of staying ahead of just about any other motorcycle in their class (with the exception of another German import, the Adler two-stroke twins, a design later copied by Yamaha). The Maico Scramblers were equipped with 3.25 x 19 inch front and 3.50 x 19 inch rear wheels, resulting in a large motorcycle similar in dimensions to British machines. The rims on the Scramblers were steel, with two attractive red painted pinstripes and heavier spokes than the road-going or Enduro versions. This use of stouter spokes where needed is indicative of Maico’s attention to detail among the other manufacturers, who would have simply used one size spoke for all applications. Later Enduros utilized a lighter rear wheel assembly to help lesson their weight in the woods. The forward part of the frame was made of oval steel tubing on the Scrambler (for optimal strength), compared with the round steel tubing used on the other versions; again showing Maico’s willingness to indulge performance riders with truly high-performance equipment. Ignition was by Bosch generator and battery, with the option of using the generator to power lights, if needed. The generator utilized an automatic spark advance, actuated by rpm increase, and fired a single spark plug. Both the Scrambler and Enduro versions shared a high exhaust, with the road version using a low-mounted street-type exhaust. All machines utilized a round 3.3 gallon chromed steel gas tank. Carburetion was via German Bing units, with a choke that worked by closing off the opening on the back of the rather ineffective “gravel-strainer” air cleaner.

The 250cc Maico, compared to the 500cc and 650cc British four-strokes it often competed against, gave remarkable performance and quickly cultivated a reputation for high quality and power. Only a decade removed from World War II, Maico’s German identity apparently presented no problem for its buyers. If anything, the motorcycle benefited from the perceived Old World, German reputation for engineering excellence. And, in the case of racing motorcyclists—interested in power and reliability—its performance in competition, not national origin, was what mattered. In light of the period marketing practices of other motorcycle manufacturers, it is interesting that Maico produced the three versions of the same motorcycle as early as 1955, marketing not only the standard road version, but also pure racing (Scrambler) and on-/off-road version (Enduro). While other manufacturers might produce a “factory racer” for North American buyers—generally, a street bike with no lights and a higher-performing engine, such as the Triumph and BSA versions—Maico stands out because the company extensively and early-on tailored their products to meet the buyer’s end use, producing an “out-of-the-crate-ready” tool. Until the early 1960s, in fact, Maico was one of very few companies producing versatile “race-ready” motorcycles as the rule, rather than as an exception to their prevailing product line.

Maico made its reputation through purpose-built off-road performance machines in the 1950s, and also exported excellent, purely road-going motorcycles to America, which were again highly praised. This practice of purposely building motorcycles for specific applications—particularly racing use—was, of course, different from the majority of other manufacturers, who made, simply, motorcycles. An English BSA, Triumph, or most any other import had to be made into what the owner wanted. To do this, the owner could buy competition engine parts, remove lights, or change tires—but the onus remained on the owner, and not on the factory. Maico approached the needs of the consumer differently. The Maico owner could start with any of three versions of the same basic motorcycle—competition, off-road/on-road, or purely on-road—and could either use the motorcycle as intended or modify it to taste, using readily available factory parts. If the buyer chose the 250cc Maico Blizzard, the road-going variant of the three machines previously discussed, it could also be easily modified by using parts from the other two versions—and likewise be placed back in road-going trim easily. This company policy was an excellent selling point for performance-oriented Americans. The Blizzard, in fact, produced with conventional telescopic front forks in 1956, and eventually equipped with a larger 280cc engine, became the pillar of the Maico mid-size trio through 1962, and no doubt many were used as part-time competition models.

Scootering on your Maico

The Maicoletta scooter, though never very popular in the United States, was still an excellent and innovative motorcycle. Available in 175cc, 250cc, and 280cc sizes, it was rather large—at least when compared to the popular Italian Vespas—and powerful and robust enough that it could even be fitted with a sidecar. The Maicoletta abounded with new technology, from its back-and-forth “rocking” engine starting, to its leading-axle front forks and high-performing engine. Another scooter, the Maico Mobil, was equipped with large front bodywork, and used the 175cc and 200cc engines.[5]

Maico also produced lighter 49cc mopeds, and 175cc, and 200cc road-going motorcycles during these years.[6] These machines were periodically imported to the United States, but like the scooters, did not gain popularity. The rationale for scooters and mopeds was one of efficient urban transportation—different than the motivation of off-road riders and racers, where utility was not at all the point. Furthermore, owing to cheap fuel and greater travel distances in the United States, very small motorcycles did not appeal to American motorcyclists at the time. (Later, in the 1960s, small motorcycles like the Honda would appeal to predominantly non-motorcyclists, for different reasons.)

[1] John F. Kasson, Civilizing the Machine: Technology and Republican Values in America. (New York: Penguin Books, 1977), passim.

[2] Jim McCabe provided much of the factual data and images in this chapter. The bulk of this data is extracted from a letter that McCabe wrote to an acquaintance for the purpose of “clearing the air” of incorrect information about early Maicos. In his letter, McCabe spent considerable time describing racing in the 1950s American mid-west, and in completing the record on the technology of early Maicos where no information currently existed. He had competed in scrambles, short track, and enduro events since 1956, beginning and finishing his riding on Maicos. McCabe was a noted amateur competitor, having finished in the top thirty riders in the famous Michigan Jackpine Enduro on a 500cc Indian. Like Charles Schank (whose remarks appear in chapter 2.3), McCabe competed in the days when one rode one’s motorcycle to an event—often a state away—completed perhaps 100 miles off-road in the most arduous conditions, and then rode the motorcycle home in order to get some sleep before getting up for work on Monday morning. McCabe, who passed away before the completion of this work, was a pre-eminent authority on all Maicos and was one of the very few experts on pre-1970 machines. He was also a long-time observer of the sport and a master mechanic who tinkered with any object housing an engine. His personal stable of projects included a vast number of Maicos as well as many other European motorcycles, and extended to airplanes—which he both repaired and flew. McCabe was most recently known for his creation of a three-cylinder 1500cc Maico—made from three 490cc engines— and was deeply involved at the time of his death in the construction of a very-large capacity single-cylinder engine, using Maico and KTM parts. He had been working to overcome the design challenges of such a motor, and hoped to build it for no other reason than to show it could be accomplished. His insights and also his contribution of many early promotional pieces and period photographs were critical to the portions of this work addressing early Maicos in America. Source: Interviews with Jim McCabe by David Russell, January 2008 and February 2009, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here. It just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

[3] Earles forks. Derivation of the front suspension designed by Englishman Ernest Earle, utilizing twin shocks and a pivot-point aft of the front axle to absorb front-end bumps. Also known as the “leading link” suspension.

[4] Interviews with Jim McCabe by David Russell.

[5] McCabe, a motorcycle expert by any measure, considered the Maicoletta scooter one of the most innovative motorbikes he had ever encountered.

[6] “Mopeds” are step-through bicycle/motorcycle-like machines, popular throughout the world to this day. Their engine capacity—usually 49cc—figured into legal regulations in both Europe and North America which permitted their use by unlicensed riders and often negated the need for registration fees. “Moped” is a contraction referring to the motor and the presence of pedals (the Moped is pedaled to start the engine, and can, with some effort, be pedaled like a bicycle).

Excellent article on early Maico history. My earliest recollection of the Maico brand was a mint green Maico enduro that my school teacher would ride to work in about 1957 i would have been in the seventh grade. It was a 250, had a high exhaust pipe, and a red dual seat. I remember the popping sound of the exhaust and the smoke from it. I have had a history of scrambles and desert racing in Illinois and California but regret that I only rode a Maico once, a 400 low pipe on a scrambles track in Illinois that belonged to a friend. Thanks for the memories the article brought back.

David–must have been a “cool teacher” (like my 6th grade teacher with her boat-window red T-bird)! Glad you found us and we could re-kindle some memories!

My 1957 Maico Scrambler was rather advanced. It had ‘up-side down’ single shock forks with upswept expansion chamber and all alloy chrome bore Mahle cylinder. Much of those type components were not generally available until the 1970s on Japanese machines.

Mr. Petty–it’s an honor to read your comments. Jim McCabe certainly agreed! Yes, well ahead. Moving forward into the future another decade or two, Selvaraj Narayana maintained that Maico essentially invented the proportions and geometry of the modern dirt bike, in 1980. v/r, Dave

Mr Russell – you say “This practice of purposely building motorcycles for specific applications—particularly racing use—was, of course, different from the majority of other manufacturers, who made, simply, motorcycles. An English BSA, Triumph, or most any other import had to be made into what the owner wanted. To do this, the owner could buy competition engine parts, remove lights, or change tires—but the onus remained on the owner, and not on the factory.”

That may have been true of British bikes imported into the US, but I can assure you that it was NOT the case elsewhere. British makers had been building and selling over the counter bikes for all sort of competitions at least as far back as the early 1930s. If you wanted an OHC four-stroke for road racing in the ’30s, you could get them from Norton, Velocette, Rudge or New Imperial; trials bikes with high ground clearance, wide ratio boxes, engines tuned for a broad spread of power from BSA, Norton, AJS, Matchless and Ariel; speedway bikes from Rudge-Whitworth, Douglas, Sunbeam, and J.A.P.; and by the early 1950s – long before there were any Maicos in Britain – there were two-stroke, purpose-built, off the shelf scramblers and trials bikes from Cotton, D.O.T, James, Francis-Barnett, and (most successful of all) Greeves, taking over dominance of the 250 class from the purpose built four-strokes, and challenging the four-strokes from BSA, AJS, Matchless and Royal Enfield in the 350 and 500 classes.

If these bikes were not being imported into the US, that was purely a choice made by your importers, and NOT because we weren’t making such bikes in England. This is a picture of an AJS 500cc scrambler, Model 18CS (1951-55), as sold to the general public by dealers.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-tXENQSnf2io/TcD-tTZW9TI/AAAAAAAAKd0/AWXXzYE-P4g/s1600/662329.jpg

With best regards,

Jack Enright, Buxton, Derbyshire, England

Mr. Enright–thank-you for the fascinating and well-reasoned reply. It’s very interesting to hear of the many competition models available, “off the shelf,” during the early-mid-twentieth century in the UK. While this market wasn’t the subject of my inquiry, I would respond with several points (essentially echoing your supposition). First, British bikes appear in North America in real numbers following World War II, and continue to populate the landscape into the fifties and sixties. Second, our imports were largely limited to Triumph/BSA/Norton, with some Royal Enfield dealerships and a smattering of some of the others you mention. I can’t account for the business choices of distributors (but will inquire, as I still have links with a former New Jersey Triumph import employee), but it does appear that dealer offerings were limited to the “street” line, along with the Triumph 650 TR6 (“desert sled”) and the small BSA Bantams and Triumph Tiger Cubs.

In North America, the changeover from four-strokes to two-strokes occurred in the very late fifties and early sixties, as two strokes with expansion chambers (ala MZ, vice simplistic exhaust pipes, such as were fitted to early Cotton/James/Francis-Barnett machines, to my understanding) such as Bultaco, Maico, and CZ made an appearance here.

A beautiful photo of the AJS!

Most sincerely (from an alumni of the dear–and now defunct–Eaton Hall College, Notts.),

Dave Russell

Many thanks for your detailed reply, Dave.

I’ve dug out some more information which may be of interest. I quote from an article written by an American dealer, the late Frank Conley (based in California). His company has been taken on by Nicholson’s Motors (California), which still supplies parts for Greeves, and for some other British makes which also used the Villiers two-stroke engine.

———————————————————————————–

“Bert Greeves believed competition improved the breed and could provide valuable exposure of the company’s name to potential buyers. In 1957 he went racing with a highly regarded motocrosser at the time, Brian Stonebridge. Stonebridge enjoyed considerable success in Britain, and the small company’s sales began to grow. In 1958, the pair traveled to the European continent to compete in the newly established FIM 250cc motocross class. In traveling Europe, Bert was shaken to discover that the British were “regarded as rather a second-rate race in sporting spheres”. This revelation caused Greeves to redouble the company’s racing efforts. The commitment paid off quickly, with Stonebridge garnering two second place finishes in the championship standings in the ensuing two years. Following the tragic death of Stonebridge in an auto accident, the company hired Dave Bickers as their rider. With a new motorcycle punched out to 246cc, Bickers won the European championship in both 1960 and 1961.

It was about this time that Greeves motorcycles began to show up in western states desert races. The little silver and blue Hawkstones began to change peoples ideas about what kind of hardware was needed to win. Before the Greeves, lightweight bikes were a joke. They were unreliable and had difficulty even finishing. Greeves changed all that. They not only finished, but were often beating the large bore desert sleds of the day. For a ten year stretch, from 1959 to 1969, Greeves motorcycles became the ones to beat.”

—————————————————————————————————–

Through this period, it’s worth noting that, by a hefty percentage, the majority of Greeves production was exported to the US. From memory (I was a keen follower of off-road sports in England at the time, and particularly of the lightweight two-strokes), my impression was that by far the bulk of Greeves exports to the US went to the west coast.

Here is the link to the article in question:

http://www.greevesguru.com/history.html

This passage from the same article may also be of interest, in showing how far advanced Bert Greeves’ thinking was at that period:

———————————————————————-

“Shortly after introduction of the Griffon line, a collaborative engineering effort began between the Greeves company and Dr. Gordon Blair of Queen’s University, Belfast. This collaboration resulted in the last significant bike to be sold by Greeves, the Griffon QUB (Queen’s University Belfast).

Driven by the market and competitive demand for greater horsepower, Greeves turned to Dr. Blair to help squeeze more ponies out of the Griffon 380. A highly regarded expert in two stroke theory, Dr. Blair and his staff re-engineered the ports and exhaust system, bumping horsepower from 38 to 44.”

———————————————————————–

Dr Blair was the brilliant engineer entrusted by Yamaha with the design and development of the RD.250 and 350 two-strokes with the Power Valve variable port-timing.

With best regards,

Jack Enright

Buxton, Derbyshire, England

Marcioletta, close I came here to see ‘the 2 wheeled car” a 197cc Maico Mobil from the whole ’50s decade:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maico_Mobil

I have a 1959 maico run what should I ask for it ?

Penny, good question. Value depends on many things inherent with the machine (not to mention economic environment). First, a running bike in excellent condition–no matter what it is–is always of some value. For all the bikes that are not in near-perfect condition, it’ll come down (again) to its condition, what the machine is, and how many people want the bike. As someone who’s no longer a youngster, I’ve seen some commodities go from valuable to not-so-valuable (e.g., Model-Ts, Cushman scooters, and Whizzer bikes). This isn’t because the machines have changed, but rather because the demographic that wanted them is passing away, or no longer in an acquisition mode. A Model-T that commanded perhaps $15K in 1990 dollars might now be driven off the lot for $10K in 2021 dollars; the reason is that their are far fewer folks who know them and want one. That said, your ’59 Maico is kind of in a special category for a special buyer; it was a quality motorcycle with a certain timeless quality for the right person. Value will also depend on which model. If you wish, email details (and pics, if possible) to ramber59@verizon.net and I’ll provide my ideas.

I’d like an opportunity to buy this if it’s still available. My uncle used to race and win on Maicos back in 58 and 59. He competed on a 175cc and is featured in many ama Publications as the winning driver in his class