No products in the cart.

Uncategorized

The Shop Owner: Gig Hamilton Pt. 2

THE SHOP OWNER: GIG HAMILTON Pt. 2

Our second article in the examination of the unique business model of retail sales, as the “motorcycle boom” of the late sixties and early seventies reached the United States. This was a time when hardware stores, used car dealerships, individual racers – and, nearly anyone with a few hundred dollars and some extra space – could become a dealer. If you haven’t read the first installment, you can find it here.

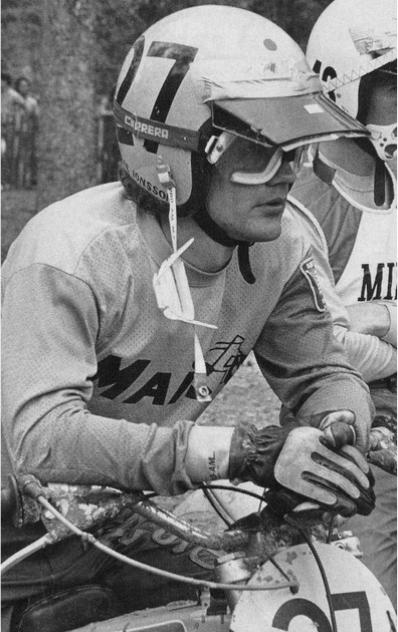

Hamilton ordered a 125cc Maico in 1969, racing in both the 125 and open classes in scrambles and “scrambles/TT” events. He was very successful as a racer, encouraged by the additional income (“I had to make money. I was driving to Ohio because they’d pay $50 to win in dirt track.”). Hamilton was awarded the #1 Plate (meaning the recipient had accumulated the maximum number of points in the past year) for six years in a row, in his home region, the western-Pennsylvania District-5 region. He never raced with the #1 plate on his bike, however, electing to stay with his original #37 racing number—and perhaps to bring undue attention to himself, which might not be for the best, as he learned in his snowmobile racing. Racing on weekends and back in the shop during the week, Hamilton achieved the dream of many motorcyclists: making a living, doing the thing he loved. His racing career spanned the years from 1964 to 1980.

AMERICAN SCRAMBLES RACING AND MAICO

American scrambles racing was also known as “TT” or “scrambles/TT,” and generally as “dirt track”—though the term dirt track also might imply other various oval-track events. Hamilton notes: “’TT’ and ‘scrambles’ were about the same thing: different districts would call the same type of course different things. They had to have the straightaway and the left and right turns. A jump wasn’t mandatory, but most [tracks] had it. This would be a high-speed, gradual, natural-terrain kind of jump. You didn’t go really high—about three or four feet—but you went really long. You’d usually hit this jump in third or fourth gear; it was really fun.” This type of racing, very dependent upon sliding technique, incorporating short heats over a smooth track, and requiring only moderate physical exertion, didn’t put the Americans in strong physical condition for motocross. When the more physically demanding sport of motocross and its European stars arrived in America about 1970, Americans riders would be on a steep conditioning and learning curve.

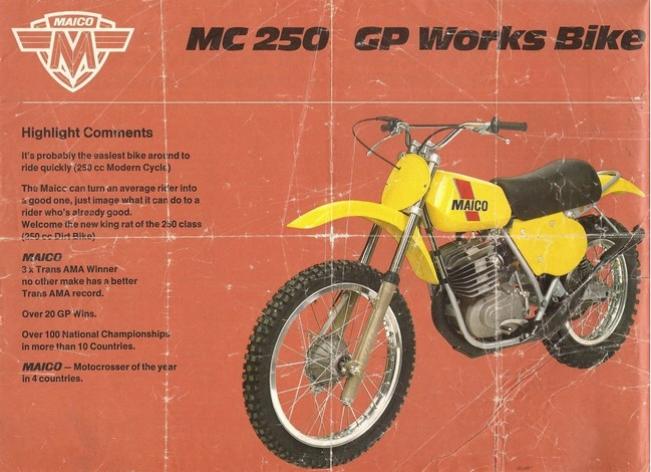

Awed by the little Maico 125’s excellent power output, but unimpressed by its almost complete lack of reliability (especially when hopped-up), Hamilton combined the best features of two manufacturers. He replaced the Maico 125 engine with one from a Yamaha 125, and now had a hybrid combining the best of two worlds; the solid and inexpensive Yamaha engine in the unsurpassed Maico frame; excellent-handling and very reliable! Racing as well in the open class, his other machine—the Maico 400—also served him well, until he obtained one of the very first 440s in the country, from Dennie Moore in 1972. Racing success verified Hamilton’s reputation as an expert mechanic, as well, and his mechanical work was sought out by other racers. He recalls that in addition to the local riders who he did work for, many other well-known riders frequented H&H Cycle. American riders Jimmy Weinert and Gary Chaplin would visit, along with the more famous European Maico team stars like Adolf Weil, Willi Bauer, Gerritt Wolsink, and brothers Ake and Tore Jonsson. Visits by Weil, Bauer, Wolsink, and the Jonssons occurred while these factory racing starts were passing through the area on the InterAm or Trans-AMA series races. Hamilton enjoyed all the international riders, and was particularly fascinated by Ake Jonsson’s professionalism and athleticism. The occasional personality differences, he felt, could have occurred in any culture, and he recalls most of the champion riders as being very unaffected by fame, and being humble and friendly to everyone they met. The European star riders would occasionally eat dinner at the homes of area dealers and racers, an event fondly remembered by the locals. Hamilton got along with them all, although the memory of his occasional disaffection with German attitudes (from the factory) does sometimes arise. As does Dennie Moore, he professes to having experienced a rare but nonetheless real harshness in the German psyche.

THE CHANGE FROM FOUR-STROKE TO TWO-STROKE

Hamilton’s biggest praise as a mechanic and tuner was his remarkable understanding of two-stroke engines, from the earliest days of the two-stroke’s rise to popularity, in the 1960s. Maico had, since their inception, utilized two-stroke engines in all their motorcycles, and Germans have long held a reputation for excellence in two-stroke engineering. The pioneering work of German motor company DKW in two-stroke design from the 1920s through the 1950s is particularly notable. For riders in the United States, long used to large four-stroke motorcycle engines like those on Harley’s and Triumphs, the practice of tuning two-stroke engines for racing was still largely a mystery the early and mid-1960s. Two-stroke design had previously been relegated to use in smaller, cheaper motorcycles in the United States and England, and it was not considered “proper” propulsion for a manly, full-sized motorcycle. Even Honda Motor Company founder Hirohito Honda reportedly loathed the noisy, oil-burning two-stroke engines, and refused for decades to have the Honda name attached to one. (The company finally broke tradition and entered the two-stroke market in 1973.) One cause of the rise of the two-strokes was that, following World War II, the rights to build German DKW-designed motorcycles were awarded to the allies as part of war-reparations compensation agreements. In the United States, Harley-Davidson interpreted the DKW design into their lightweight Hummer model, and in England BSA made a similarly low-end variant known as the Bantam. Still, the whining, smoking little bikes did not endear themselves to most Americans, whose open roads embraced the large, heavy four-stroke Harleys, Indians, and by then the bigger-displacement British imports. Further hurting the acceptance of two-strokes was the very limited understanding of their performance; specifically, that of cylinder porting and “expansion chamber” exhaust design.

The introduction of high-performance, larger-displacement two-stroke dirt bikes to America and around the world in the mid-1960s was transformative; it was a watershed development and afterwards the scene was forever changed. These motorcycles may have belched blue smoke and their un-muffled exhausts churned out excruciating noise, but they were undeniably powerful and fast. The CZs, Maicos, and Husqvarnas of the era weighed much less than all the then-dominant four-strokes, and put out not only greater, and more usable power. Furthermore, they were simpler and cheaper to build, operate, and repair than the four-strokes. Within just a few years, the large four-stroke singles and twins were completely supplanted by lighter, better-handling, and [at least] equally-powerful, two-strokes. Hamilton embraced two-stroke technology from its early introduction in the form of the small imported motorcycles that he first raced, and progressed into the maintaining and tuning of the larger Maicos. Maico engineers had, years before, absorbed the advancements made by earlier DKW engineers, and understood expansion chamber design—that is, harnessing the exhaust shock wave to help “pull” the next exhaust charge from the cylinder—and were building powerful two-stroke motorcycles since the 1950s. Hamilton tuned both his own motorcycles and those of his customers to the limit of reliability, extracting maximum horsepower and tailoring power output to the rider’s preferences. He was and still is known for his understanding of all the Maico engines, from the “Swiss watch-like” 125, to the big 440s and 501s. Hamilton was also one of very few Maico mechanics or riders who understood the design flaws in the early 250 radial engines.

THE STORY OF AKE JONSSON AND THE HALF-MILE RACE

It was in the course of his work with Maico and Dennie Moore that Hamilton met many of the Maico factory riders of the 1970s. In the early days of the Trans-AMA series, the Maico entourage, including the factory stars and local American racers, stopped in at Moore’s Eastern Maico Distributors location to prepare for the series. Since Hamilton was Moore’s first franchisee and was located within an hour’s drive, the factory riders would stop by Hamilton’s shop to convey the latest factory technical upgrades (part of the job description for the team), and also to go riding with Hamilton and Moore in off-hours. One weekend, Hamilton and Moore decided to indoctrinate Swedish motocross genius Ake Jonsson in the techniques of American flat-track racing—a form of racing quite foreign to the motocross-specialist, Jonsson. Hamilton recalled, “One of the neatest things was the night that Dennie and I talked Ake into going half-mile racing with us. It was a pea-gravel track in Gratz, Pennsylvania. Now, Gratz was a big half-mile; measuring half a mile on the inside of the turn, and probably three-quarters of a mile on the outside. We talked him into it.”

As Hamilton prepared the bikes, Jonsson watched in amazement as riders exceeded 100 mph down the straights, and then flung the motorcycles sideways in extreme, edge-of-control, two-wheel-drifting slides around the corners. “I’m getting this baby ready and we’re putting the sprockets on. And he keeps saying, ‘Oh, my, no . . . crazy Americans!’ But it was funny; we were all having a good time. He practiced, and then he wasn’t going to race, and then he was. Anyway, he decides he’s traveled all this way, so he might as well do it. He got a good start, not too far back; pulls ahead of several riders. But, then he enters the first curve, and he squares it off! Oh, my gosh! We thought the other riders were going to kill him! You know, you have to get in there sideways, but he squares it off! Oh, he hit a couple people, and it was bad. He made a lap, and then just pulled off and parked his bike, and said, “Crazy! Too fast—no good!’ And, that was it. We never talked him into going flat-tracking with us again!” Jonsson may have been the best motocrosser in the world, but in the traditional American venue of flat-track, even he had things to learn.

AKE AND GERRITT TAKE A RIDE

Another time, in 1973, Hamilton took Ake Jonsson and Dutchman Gerritt Wolsink riding in the local strip-mine area; what they locals called “Northy,” north of Philipsburg, Pennsylvania. He was duly amazed: “When they started riding, you just wanted to watch. It’s funny because they were so fast after one or two laps, that I didn’t even want to ride with them. One part was a really neat, long hill; you went over the top, and then you went down around a turn and off this hill. You had to watch your braking coming down this hill, because at the bottom were these two trees that you had to come down through, and you only had about six inches [clearance] on either side, so you had to be pretty precise. So . . . I watched them take a couple laps on this track. . . . They put in about three laps, and it wasn’t exciting enough for them, I guess. So, then they run this hill-climb, and almost at the very top they square off the top and make a left, and square again and made a ninety-degree turn right. So, they go up over this hill—that we can barely make it up, most of the time—make a left and then a right over the top! And then they make some little ‘S’ turns, and then they come flying down off the hill, where I was saying you had to be so precise . . . .like in third gear! They were so fast and so amazing. I was just glad to be able to ride with them . . . although I couldn’t have stayed with them at all on a motocross track.”

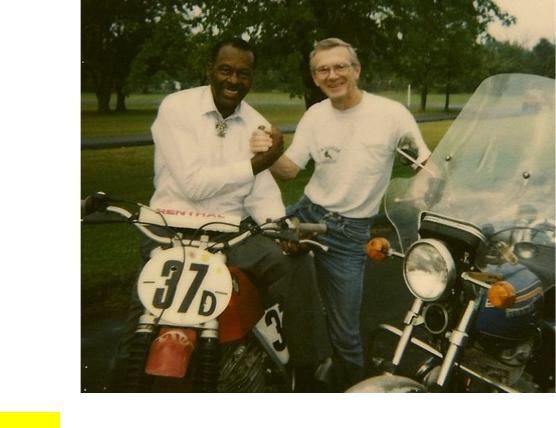

CHUCK BERRY—MAICO MAN?

Hamilton has a unique friendship with another humbly-born American who pulled himself up through similar hard work—and who also benefited from Hamilton’s motorcycle repair skills. Hamilton’s cousin, nicknamed “Sasa,” has been rock-and-roller Chuck Berry’s manager for many decades. Berry is one of the genre’s pioneering stars and an early inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. An African-American, his career started in the 1950s and continues today. Through Sasa, Hamilton came to know Berry quite well, and often stopped-in to the singer’s Missouri estate when riding to races in the area. Berry’s career was marked by legal problems and mismanagement at the hands of white promoters, and his encounters with police were many. The two men’s misadventures, undertaken while pursuing similarly unaccepted career paths (rock and roll, motorcycle racing) helped the two forge the camaraderie that they did. Hamilton recalls, “He has a place in Wentzville, Missouri, called Berry Park. . . . I used to go out every year and spend a week [with my cousin, Sasa]; most of the times, Chuck was there. He’s a real nice, straight person . . . for as much crap as he’s gotten in his life. He’s always treated me good. Once, he came to [play a concert near our winter home in] Silver Springs, Florida a few years ago. Called us up, and told Nancy and me to meet him back-stage. So, we went down on the bike. Of course, when we got there, the security didn’t believe us; I told them to go get Chuck. Me and Nance on the BMW, just sitting there . . . pretty soon I here, ‘What’re ya doin’ over there, Gig? Come on over; where do you want to sit?’ Spent the whole day with him. . . . Seventy-nine years old, and in great health.”

“And then, five or six years ago, I was racing at Peoria, Illinois, not far from Wentzville. Another cousin was with me . . . so, we stopped to see Sasa for the day. Chuck just happened to be there; remember that his offices and recording studio are right there at Berry Park. My cousin’s house is also there on the property. I went over to the studio where he was working, to say hello, and happened to ask if he still had that old Honda 400 we used to ride, back in the 1970s. He said, ‘Sure, let’s go find it.’ He was positive it was there, somewhere. Well, finally, in the fourth building we checked, there it was; that old Honda automatic with a couple hundred miles on it. He told me that that bike had never left Berry Park. He asked me if I wanted it. ‘You rode it, you worked on it—it’s yours. I want you to have it.’ He gave me a bill of sale that day; I still have it, with his name on it, along with a matching helmet. I bought it for one dollar! Chuck . . . he had an incredible, and not always easy, life. A hard-working guy. He’ll still do the Duck Walk, but he says he’ll do it only one time each show, now.”

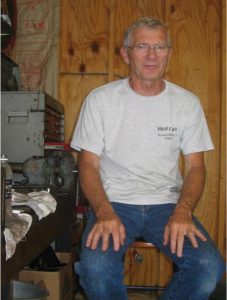

Hamilton is retired, now, living out in the country around Osceola Mills in the summer, and spending the winter months at his small home in rural Florida, where he hunts snakes, fishes, rides his old street bikes, and still works on an engine, if prodded. He remains proud of his work and cherishes his experiences. “The Maicos ran good from the 1960s when I sold them, and they run good today. . . . You couldn’t beat a Maico through the early seventies; after that, the Japanese really had a good motor. But look at DeCoster—he was on a $30,000 hand-built [Suzuki], and he couldn’t beat Ake [Jonsson] on a basically stock Maico.”

A LOOK BACK AT THE MAICO AND THE MOTORCYCLE INDUSTRY IN THE “BOOM” YEARS

Towards the end of Hamilton’s time as a Maico dealer, his relationship with the company soured. The old, casual understanding between the far-away German company that made excellent motorcycles, and the small, rural family dealers across the United States, deteriorated. Dennie Moore was pushed out of the business in 1973, and for Hamilton, relations went downhill from that point. “A funny part of my relationship with Maico is that Maico told me, in 1982, that I wasn’t selling enough bikes. I really didn’t like their bikes in 1981 or 1982. Maico really got on me and told me I’d lose my franchise if I didn’t stock eight to ten bikes. I thought this was a bit funny, since I was the second dealer set up in Pennsylvania, and had sold, serviced, and raced them for years, winning motocross, dirt track, and scrambles with the #1 plate. And Maico wants to pull my franchise? Do you know what they told me? ‘Times have changed.’ What kind of BS is that? One of the first dealers, putting out a good name, and here they are putting out bikes that needed to be improved upon—it was a proven fact—and they treated me like that? I really had a round with them; I told them that that was fine. They were making a bad bike, and I frankly didn’t need them. In 1982 I didn’t buy a single bike, because I was so mad at them. I got a letter that year, saying that they were going to pull my franchise in 1983; of course, that never happened [due to Maico’s bankruptcy that year].”

“Funny, too . . . right now, 1981 Maicos are so valuable; at the time, I didn’t think the [1981] bikes were that great. They were a really good motorcycle up until the 1980s, but that’s when problems started: breaking hubs and gears; you really had to watch it. . . . There were lawsuits and I really backed off. I sold quite a few Maicos; pushed them pretty hard up until the late 1970s. I think they were starting to go downhill even then. In 1981 I believe I only sold two bikes. And, my goodness . . . the price! Yamahas were hundreds of dollars cheaper. Things change. . . . I became a bit burnt-out . . . ‘Things change.’ Funny.”

“I had a great time. I had a blast. It was a lot of fun; but I’ve had friends killed, paralyzed; broken necks, broken backs . . . it can be bad. I was really fortunate. I once broke a bone in my foot; down near the middle. It was at Murraysville Raceway in the early 70s. Boy, it hurt; evidently I caught a foot-peg or something. Took the boot off and there’s that bone—not sticking quite through the skin, but you could see it trying to. Back in those days you just taped it up. In the 1960s the ambulance driver would just get rid of the blood, tape you up, and get you back on the track. I could tell you stories for a week. We had a blast!”

Hamilton’s business model, a small building with a one-man operation, was common in the 1960s and 1970s. In time, the industry did change significantly: less competitive and smaller manufacturers were pushed out, and the stronger surviving companies worked to create more compliant, efficient, uniform, and profitable dealer networks. The first casualties of this reorganization were small dealers. Other than a few businesses dealing with the remaining “boutique” motorcycle brands still in existence, the small Mom and Pop dealership is now mostly gone from the United States landscape. H&H Cycle remains, though no longer a dealer for new motorcycles, concentrating now on parts sales and mechanical work.

Had Maico remained viable, in the face of both its own missteps and the escalating competition from the Japanese manufacturers, H&H Cycle and other small dealers may have continued selling high-quality European imported motorcycles. But this was not to be, as the small manufacturers like CZ, Monark, Puch, and Husqvarna—suffering like Maico, from bad assumptions and increased competition—continued to lose market share. The modern era of off-road motorcycles is now one dominated by the Japanese factories, with KTM and Husqvarna surviving as the non-Japanese option.

It’s winter, now, in Pennsylvania. The little turtles are firmly in their muddy, dark hibernation, and the ponds are all frozen over. Time for Gig Hamilton to pack the RV and head to Florida, for warmth, fishing, street riding, and a few memories!