No products in the cart.

Maico, Motorcycle Culture, Trail Bikes

The History of Maico Motorcycles and American Sport Motorcycle Culture – Preface, Part 2

The Maico – The People and the Culture

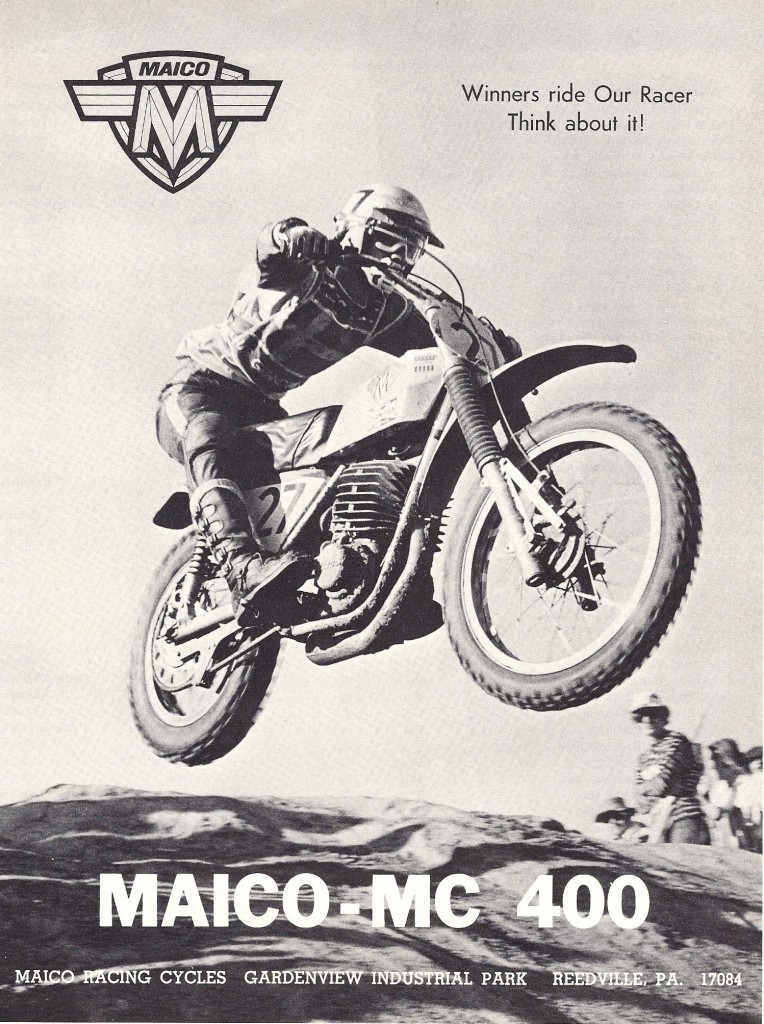

As the premier tool used by the most dedicated racers of the time, I see the Maico motorcycle as an excellent touchstone for this little-studied American group. By analyzing the motorcycle as material culture and studying the relationship between this machine and the people who interacted with it, we will learn something new about this driven and individualistic fraternity, as well as within the greater society. This rugged, unusual old foreign motorcycle is the nexus of an equally rough, independent group of American sportsmen. And this group, despite youth, long hair, and a passion for fast motorcycles, differed significantly from the 1960s and 1970s typecasts into which observers have tended to place all American youth at this juncture. For this reason, it is worth our study.

Minimal research has been done on the subject of sport and off-road riding in its most popular years in the United States. And virtually nothing has been written about Maico motorcycles in even the popular press. This latter point is surprising, considering the brand’s history in American riding and racing, and technical importance in the continuum of motorcycle development.[1] This dissertation fills both these gaps, as it extracts meaning from the motorcycle about its owners, and also helps construct a body of information about the motorcycle. Throughout this examination I will work to create a strong description of these largely dismissed American sport riders. For reasons likely related to the (sometimes) more titillating and sensational nature of other motorcycle cultures, what academic analysis has been done on 1970s American motorcycling tends to address these sectors exclusively, and ignores all others. This dissertation will focus missing scholarly attention on the neglected culture of off-road motorcycle riding, as opposed to the other, more frequently studied groups. Looking back to a pivotal work in the small constellation of motorcycle literature (Thompson’s Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga) we must accept that it is a book about a tiny faction of American motorcycling. While those who study motorcycle culture will draw conclusions between Thompson’s work and the larger American culture, it is a link which should not be overemphasized. The several thousand active members of all anti-social outlaw clubs of the 1960s and 1970s may in fact say no more or less about the American condition than several thousand members of any other popular group of the time—whether it be the professional bowling circuit of the 1960s or fans of the rock group Kiss in the 1970s. There is a much more representative group of motorcyclists that no one has yet addressed. This work will help fill that vacuum in contextual analysis of motorcycling in the United States.

A Boy and a New Generation

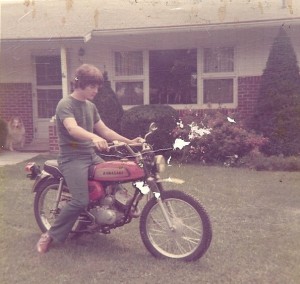

As a young boy growing up in this golden era (I was thirteen when I got my first motorcycle in 1972) I and others of my generation were there during the enormous surge in popularity of motorcycles and all the other seismic cultural metamorphoses of the era. It was a period of great change in so many areas, not just in motorcycling. Both the war in Viet Nam and the Nixon presidency were winding down, and the youth culture of the late 1960s was giving way to a more modern and even more confused 1970s. The “Me Decade” came into being, and American culture reeled with change from every side, as a new urge to attain personal fulfillment and a sense of unlimited personal choice gave people different priorities than that of their parents’ generation.[2] Many young men and women whose fathers willingly fought World War II and whose mothers raised nice future homemakers appeared to hold diametrically-opposed views of the future and their roles in it. We were still fighting the Cold War and accepted mutual nuclear annihilation as a real and foreseeable eventuality, as we embarked upon detante with the Soviet Union. The 1970s were the heyday of hedonism, we learned, with the Sexual Revolution and the arrival of mainstream drug culture. Aesthetically, the drive to be different and new led to some questionable ends: 1970s popular art, design, and philosophy were, in some cases, perhaps best left in that era. The legal framework of racial segregation in the South was finished, but the follow-on hard work of integration and the attainment of actual equal rights across the nation was certainly not.[3] The 1970s were particularly chaotic, and much of what came during the 1980s is seen by some as essentially a reaction to the previous decade’s excesses.

Boys and Their Trail Bikes

On another more microscopic level, the large Japanese motorcycle manufacturers were completing their domination of the former sales leaders at Norton-Villiers-Triumph in England and Harley-Davidson in the United States. Boutique manufactures, smaller and more flexible, flourished for the time being in Spain, Germany, Sweden, Austria, and Italy. Closer to home, in an age before computer entertainment, young suburban boys bought mini-bikes and small Japanese “trail bikes.” As previously mentioned, the sales of these primarily off-road motorcycles, along with the more exotic European dirt bikes, had burgeoned to 165,000 (of over 1 million total motorcycles sold in the United States) for the year 1970.[4] For these machines, young boys constructed trails and jumps and racetracks, eluding the local police as they made their way after school to the not-yet-NO-TRESPASSING gravel pit, farmland, or edge-of-the-neighborhood vacant lot, the next new suburban development over. When Dirt Bike Magazine careened onto the established motorcycle press landscape that same year, these boys quoted its articles with reverence, admiring from afar those mystical Husqvarnas, Bultacos, Maicos, and the other unobtainable Euro-motorcycles displayed in its pages. They took the lights and fenders off their Japanese trail bikes, put a knobby tire on the rear and a Bel-Ray Oil sticker on the tank, and pretended they were the stars in the magazine. In Lower Paxton Junior High School near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, we boys spent the last period of the day in Mrs. Turns’ stifling seventh-grade English classroom, daydreaming about exotic dirt bikes and drawing brilliant new engine designs on our yellow lined tablet paper, when we were supposed to be conjugating verbs. A few of us, with fathers either understanding and cool beyond all belief (in our own adolescent minds, at least), or absolutely irresponsible (in our mothers’ minds), got to actually race motocross or scrambles with the new Japanese YZs, RMs, KXs, CRs, or even hot little European 125s. We played baseball, rode our motorcycles in the vacant lots, and thought incessantly about girls . . . and motorcycles.

Then we grew up, and left our bikes behind. For a while, at least.

[1] Maico’s contribution to motorcycle suspension design and overall frame geometry will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

[2] David Frum, How We Got Here (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 351.

[3] Kelly Boyer Sagert, The 1970s (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007), 20-24.

[4] Ed Youngblood, “The Birth of the Dirt Bike,” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, July, 2007, http://ijms.nova.edu/July2007/IJMS_Artcl.Youngblood.html.

Well, you are quite right. This must a be little researched or talked about group because I have never heard or come across anything about the Maico motorcycles! This is an interesting and informative read about this culture and era. I appreciated reading this “slice” of history and even seeing how it relates to the motorcycle world of today. Thanks for sharing this information!

Thanks, Sal.

There’s nothing particularly special about the Maico, I should say. It was an excellent competition motorcycle–like many out there–and I simply chose it to be my ‘lens’ into the culture because of my attraction to the brand. More to come! Dave

Just desire to say your article is as astonishing.

The clarity to your put up is simply cool and that i could assume you’re a professional on this subject.

Fine together with your permission allow me to seize your feed

to stay up to date with approaching post. Thank you a million and please carry

on the rewarding work.

Glad you enjoyed it. Absolutely feel free to feed our articles!

Hi i am kavin, its my first occasion to commenting anyplace, when i read this

article i thought i could also make comment due to this good paragraph.

Glad you liked it Kavin! Stay posted, we’ll continue to write top notch articles examining the vintage motorcycle world. – Dave

Thanks, glad you like the site. Keep on reading!

The bottom line is that morstcycliot demographics show that riders are getting older. I’ve been riding bikes non-stop since the mid 70’s. Go to any of the big rallies like Americade, Bike Week, or a national BMW rally. Most of the participants are over 50.The younger folks just haven’t taken to bikes as the previous generations. Same with camping, horses, stamp collecting, and many other pursuits.

I believe the average age of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America is now 56. And, of course, as you note, the age of first-time motorcyclists has gone up, according to Gov stats.

That seems to be the case! And the question is why? Some authors have suggested that Americans don’t tend to cleave onto groups anymore. They tend to group onto individual things… could be the cost as well.

Hi! I’ve been following your site for some time now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from Humble

Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the excellent work!

Thanks for the shout out!

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to shoot

you an email. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might

be interested in hearing. Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

Sure, we have a Contact Us link at the top of the website. Or vintagemotortees@gmail.com. Thanks!