No products in the cart.

Maico, Motorcycle Culture

The History of Maico Motorcycles and American Sport Motorcycle Culture – Part 1

By David Russell

Introduction

Most Americans would profess to some basic knowledge of the culture and history of motorcycling in this country. Some among them have likely encountered Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga , and may have at least attempted to absorb Robert M. Persig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance ; surely the most-referenced text, ostensibly having something to do with motorcycles (even if few people ever actually read it). And, when Americans think of a motorcyclist in visual terms, they likely picture black leather, a certain display of “attitude,” and a big, loud street bike. Most of us over the age of fifty have also seen two seminal “biker” movies: 1969’s Easy Rider, starring Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper on the road and “looking for America;” and 1954’s The Wild One, showcasing the young Marlon Brando in the first major movie about anti-social motorcyclists in the United States. From this short list of motorcycle popular culture and their own observations, Americans would probably attest to several basic beliefs about motorcycling in the United States. Several of these assumptions might include:

- Motorcycle people are tough guys—and occasionally girls—who sometimes get into trouble with authority, but are really just non-conformists; or,

- Motorcycle people are usually socially-deviant bums.

- Riding a motorcycle is about freedom, in various ways, and showing one’s individuality.

- Motorcycles are good because they are cheaper to operate than cars. This makes motorcycles the transportation for the working class.

- Motorcycles are dangerous. One must be crazy to ride one.

Cultural Beliefs

These and other be liefs about motorcycle culture in the United States tend to be based on a montage of popular media products and from what we see on our public streets. Often these beliefs are highly opinionated; some are simply incorrect. Further considering stereotypes, we discover a default visual image of the motorcyclist as a black-leather-clad street rider. More often than not, the motorcyclist in this image is male, and the motorcycle is of course an American-made Harley-Davidson. In fairness, there is good reason for all these impressions: the primary vantage point for observation of motorcyclists is, of course, on the road; there is nothing wrong with thick leather (between you and the street); the majority of motorcycle road riders are quite obviously male; and Harley-Davidson now sells roughly half of all new street motorcycles purchased in the United States. Still, this composite image leaves out a vast and ever-present group of American riders. Since the motorcycle’s appearance as a mass-produced item in the United States (the period 1902 to1903), motorcyclists have done much more than cruise down public streets. For many Americans, competition was the natural application of the motorcycle. As a former professional racer interviewed for this dissertation said about Americans and motorized vehicles, “Whenever two vehicles with engines are involved, there’s gonna be a race.” It is these competitive “sport” motorcyclists, off the public roads and largely invisible, that we generally overlook in the motorcycle world.

liefs about motorcycle culture in the United States tend to be based on a montage of popular media products and from what we see on our public streets. Often these beliefs are highly opinionated; some are simply incorrect. Further considering stereotypes, we discover a default visual image of the motorcyclist as a black-leather-clad street rider. More often than not, the motorcyclist in this image is male, and the motorcycle is of course an American-made Harley-Davidson. In fairness, there is good reason for all these impressions: the primary vantage point for observation of motorcyclists is, of course, on the road; there is nothing wrong with thick leather (between you and the street); the majority of motorcycle road riders are quite obviously male; and Harley-Davidson now sells roughly half of all new street motorcycles purchased in the United States. Still, this composite image leaves out a vast and ever-present group of American riders. Since the motorcycle’s appearance as a mass-produced item in the United States (the period 1902 to1903), motorcyclists have done much more than cruise down public streets. For many Americans, competition was the natural application of the motorcycle. As a former professional racer interviewed for this dissertation said about Americans and motorized vehicles, “Whenever two vehicles with engines are involved, there’s gonna be a race.” It is these competitive “sport” motorcyclists, off the public roads and largely invisible, that we generally overlook in the motorcycle world.

The Sport Riders

The prediction of two or more engines necessitating a race appears to have truly been the case in the motorcycle’s early years in the United States, as competition is recorded virtually simultaneously with the first motorcycles. Indian motorcycles are on record as winning organized competition events in 1903, the first year of substantial production. In just a few more years, the company was sponsoring its own racing team. Many Americans competed on motorcycles from their first exposure, and these ranks have always constituted an important part of the riding population. This performance-oriented component of American riders (which I will call “off-road,” “competition,” or “sport riders;” these terms will be discussed in chapter 1.1) was and remains much less observable than the visible community of riders sharing America’s highways with the rest of us. We do sometimes get a glance at them; on the highway as they haul their dirt bikes or road-racers to weekend meetings, on trailers or in the backs of pick-up trucks. Perhaps we note them swilling a Gatorade at the gas station, recounting the day over muddy motorcycles; but that is the limit of the interaction most Americans have with sport motorcycle riders. Examining this group more closely, we find that it includes recreational and competitive riders who specialize in varied activities. The competition venues nowadays include natural-terrain (motocross, trials, endure, and hill-climbing), paved surfaces (drag racing and closed-circuit “road”-racing), and manicured gravel outdoor courses (mile and half-mile “dirt track” or “flat track” racing). Non-competitive sport riding includes off-road riding, anywhere. Of fundamental importance is their engagement in some sort of competition, or in challenging their own physical abilities and limitations riding the motorcycle (as opposed to the act of riding a motorcycle on the road, which is the use of the machine as transportation). Thus, these two groups differ at a most basic level: one is competition and physically oriented, and the other is largely transportation oriented.

Considering the types of riding engaged in by these sport riders—and I will discuss specific details of these venues, later—an important assumption can be inferred about them and their relationship to transportation motorcyclists. This is, that although the sporting riders are not as visible or (sometimes) as luridly interesting as the on-road bikers, their skill levels and dedication to the act of riding must signify something real and substantial about their credibility as motorcyclists (given the fact that they take their machines to the limits of their own physical and mechanical abilities). The riding skill level of a sport rider is usually substantial; this may or may not be the case with the road rider. Yet it is the black-leather-and-dangling-cigarette biker who is considered the epitome of a motorcyclist. Furthermore, he (or she) is accepted as not only the symbol of motorcycling in the United States, but also a sort of barometer for the American condition; particularly emblematic of the angst and alienation of the individual within the greater society (which in turn is seeking to conform and depersonalize the biker). The biker is envisioned as a reflection of American attitudes, identity, and values. This implied proximity between the Harley-Davidson motorcycle (in particular) and America can be seen in titles such as Travels with Harley in Search of America by E. Michael Jones , and Outlaw Machines: Harley-Davidson and the Search for the American Soul, by Brock Yates . The Harley-Davidson and Philosophy collection, meanwhile, suggests an even deeper meaning; promising an enlightening draught from the wellspring of Harley mystique and wisdom.

The Outlaws

The outlaws and Harley bikers do have a story that warrants examination, and their symbolic status is undeniably worth study. Yet theirs is not the only story. Sport riding in America, largely passed over by scholars, deserves inquiry as well. In this dissertation I propose that the off-road and sporting riders are just as much, if not more, a bastion of American masculinity and individualism as the on-road, black leather, transportation bikers. Sporting riders live by and espouse the values that Americans have traditionally considered their own. Even when masculinity and individualism were cast suspiciously at times following the 1950s, their acceptance within motorcycle racing subcultures never wavered, as I illustrate in succeeding chapters. While sporting riders share bonds with on-road biker culture—living close to physical danger and the joy of riding, at a minimum—they also differ in fundamental ways; most ways, actually. Examining them through the lens of one particularly elite motorcycle’s popularity in the United States, at the highpoint of motorcycle interest in the country (primarily the 1970s decade and several years on either side), I will describe this group. I will show that the sporting riders tended to be male and to arise from working-class roots; that they were often apolitical, prized individual courage and personal responsibility, and held a generally conservative cultural outlook. I will also illustrate that sport motorcycle culture was and is a shared one, with commonly-held values and behaviors, and that the individualist nature of the competitor allowed him a true sense of “freedom” within this fraternity. This last characteristic, in particular, differs greatly from that of some road-riding communities, where often rigid adherence to requisite manners of dress and behavior is mandatory.

Maico

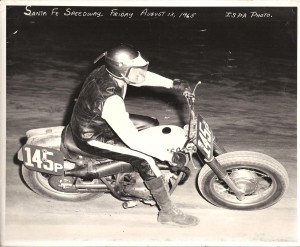

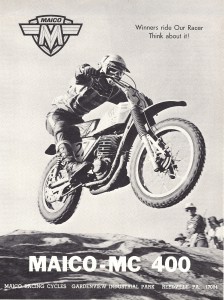

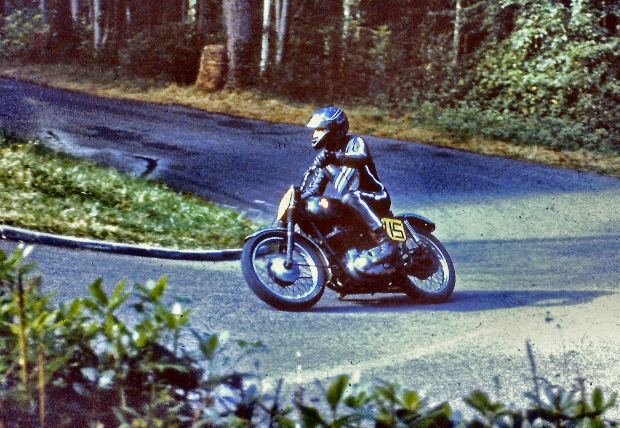

The motorcycle/object/artifact by which the both the individual and the community will be examined is the Maico competition motorcycle. The Maico reached its pinnacle of popularity in the late 1960s through the early 1970s, and was no longer produced after 1983. My analysis of the object follows commonly accepted processes of material culture inquiry. Several of these methods, along with my chosen hybrid approach, are described in chapter 1.1. Driven by the artifact’s dates of use, this dissertation focuses on the late 1960s through the early 1980s, but the findings are relevant today. Looking back to these years and the “motorcycle boom” in sales around the world, the sporting and off-road aspect of motorcycling was particularly vibrant. To place this sales boom in perspective, purchases of new off-road motorcycles alone in 1970 (165,000 units) were more than four times greater than the total number of all motorcycles sold in the United States, fifteen years earlier in 1955. Of all new motorcycles sold in the United States during these peak years, more than one in six was never built to be ridden on the road. Furthermore, many more street-legal bikes had their lights and road equipment stripped off by owners; these saw little or no road use, likewise becoming off-road play-bikes or racing machines. The increased popularity of sport riding and racing was brought on by a combination of excellent machines, an (initial) unfettered access to riding areas, and a renewed general interest in motorcycles. Another instigator of off-road riding was the arrival and popularity of the new sport of motocross. Motocross—competition on a closed-circuit, rugged natural terrain course—had recently made its way from Europe to the United States, and was replacing the more sedate amateur scrambles racing and professional flat-track racing that had dominated American motorcycle sport for two decades. As Ed Youngblood notes, motocross and the availability of the new, lightweight two-stroke motorcycles significantly altered the nature of motorcycle sport in the United States: in 1965, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) sanctioned fifteen motocross races; in 1975 it sanctioned 1,500, a one-hundred-fold increase. At the center of all this activity were the most serious racers, and their motorcycle of choice was often an expensive, pure-bred, German, and sometimes unreliable and frustrating racing machine, with unique aesthetics. This motorcycle was the Maico.

To view one of David’s hand designed Maico T-shirts, click here

David,

I am one of the sport riders from the 70’s. I rode sport bikes before I rode street bikes. I did own three Harley’s toward the end of my riding. Several accidents and back surgery and the doc said no more riding if you want to walk.

Great read on your article, many memories. Went to many flat track races at the Duquoin Mile in the 70’s also. Still have my dads kidney belt and nylon helmet from the 40′ when he rode his Harley. He rode into his 70’s.

John

Hi, John,

Thanks for the note. As you can see–and probably agree–we sport riders got something of the short end of the stick regarding our stance in the sport in the United States. Of course, the important thing was that we were able to ride and enjoy ourselves when we did. I still putt around on some old trail bikes and the Triumph street bike. Nothing like when we were kids, but we sure have the memories! Sincerely, Dave PS–this essay was the beginning of a longer writing, using Maico motorcycles in the 1970s as the touchstone; you might like the subsequent chapters, as they’re posted.

I really enjoy you site and think that it is very

interesting to learn about the history of

motorcycles. I think that a lot of the

assumptions about motorcycle riders

that you mentioned are true and I liked

how you gave more of an explanation for them.

What kind of motorcycle do you think

is the best?

i really like this article because i love motorcycles i think they are wonderful machines and learning about the history of them fascinates me

I would like to know what your thoughts are on BMW bikes compared to Ducati bikes, I may considering purchasing one in the future

I really liked how you said motorcycle guys are tough guys

BMWs and Ducatis are both wonderful bikes. The newer ones can, however, be expensive to maintain. Just like with an aircraft, high-tech doesn’t mean low-maintenance!

Hi David,

Well done with this article, I started looking back over old college notes and began reading up on the development of harley davidson and the HOG. I stumbled across this piece and particularly enjoyed being able to see the more romantic cultural side of biking. Keep up the good work. Thanks!

Thanks for the encouragement Paddy, glad you enjoyed the article…I’ll have to write a piece in the future on the development of Hog and Harley Davidson. Thanks for the inspiration 🙂

Hi,

Pretty awesome article. I’m always searching the internet looking for websites that I can follow that pertain to motorcycles and that’s how I found your website.

I was wondering what you think about the endure motorcycle class?

I know that there are a lot of enduro riders out there these days that are all about adventure riding. The whole adventure riding culture has a huge following and specific bikes even have a big following.

The two that stand out the most to me are the BMW Adventurer and the KLR 650.

These two bikes are on the oposing end of the enduro world and there are a whole lot of others somewhere in between.

The KLR is the one of the most affordable enduros on the market and not only that but they are almost bulletproof. With the simple design and the fact that they’ve barely changed in decades it makes them a super practical choice. Not to mention there isn’t a whole lot of terrain they can’t do.

Then the BMW Adventurer is on the other end of the spectrum. Very expensive with high performance and all the fancy gadgets.

They are awesome bikes and very popular but I wouldn’t want to break down with one id a developing country because good luck fixing it yourself.

Cheers,

Robert

A tip of the hat David Russell on your insightful look into the racing history of Tim Hart, truly one of American Motocross’s founding fathers. Your article was telling, historically accurate, and captured the true essences of Tim Hart. I can make this claim being one of his closest friends since we were doing wheelies on Stingrays on Loftyview Drive. Because of Tim shyness and quiet demeanor, he is often overlooked as one of American Motocross’s true legends. You did an excellent job of pulling his accomplishments out of the shadows and giving his contribution the credit it so richly deserves. Bravo. Steve Urgo

Thank-you again, Steve, for the kind words. Tim Hart was indeed an icon that a host of formerly-young-boys-looking-at-bike-magazines will never forget. His image is unforgettable, and we’re all grateful for it. It’s been an honor! Most sincerely, Dave