No products in the cart.

Early Motocross, Early Motorcycle History, German motorcycles

SMALL MAICOS: THE 125s (Continued)

A continuation in our investigation of 125 Maicos; the first part of the series you can find here.

Preparation: Getting Ready to Ride

The 125 Maico was a dichotomy. On one hand, it used a superb, unbreakable, fine handling frame. It had excellent suspension. It was light, and the engine produced the most horsepower of any other 125 at the time. On the other hand…there was that engine and transmission! When Charles Schank prepared for competition, he first ensured that several basic maintenance tasks were accomplished on his 125s. As previously mentioned, Schank disassembled the engine of every 125 Maico he obtained—new or old—and ensured that the outer left crankshaft bearing was properly adjusted. With this issue addressed, Schank’s 125 engines lasted for years, even when ridden hard every weekend. The external shifter selector mechanism needed to be greased after every use. Ignition points were cleaned with emery cloth before being set, then cleaned with paper. The use of a Delco automotive cam lubricant on the breaker and crankshaft cam helped to keep the cam from wearing down the breaker composite material too quickly—and also helped to keep the cam itself from wearing. “I’ve noticed that a lot of used engines have the [cam lobe] chrome completely worn off,” Schank remembers.

Now…making it even faster

Schank competed in both motocross and enduro events, and was not above looking for extra horsepower from his 125s. He went about his quest this way: First, he cut the rotary-valve disc on his motocross mount down to timing specifications “in-between” that of the highly-tuned road-racer and the stock MC/GS model 125s. Then, he moved to the cylinder. For both his motocross and enduro motorcycles, he cut the stock cylinder ports exactly like those of the road-racer. Seeing that the road-racer’s low-end torque was not sufficient for his needs, he added length to the first section of exhaust pipe, coming from the cylinder (called the “header pipe”).[1] Schank used the stock muffler for noise reduction, but usually “opened up a hole in the middle.” This entire process, for the enduro bike, resulted in a machine which “. . . had a nice broad power-band, which, when I needed speed on the road, would rev like a road-racing machine! It definitely had extra power, when wide-open.” Thus, like many 125 Maico tuners, Schank used 125 Maico road-racer porting. But he did so with two key actions: First, he corrected the bearing issue which affected early 125s, and, second,he added to the exhaust header, to keep some low-end grunt.

Gig Hamilton, a Pennsylvania Maico dealer and racer who depended upon racing winnings to support his family, was—unlike Schank—not content with moderate engine performance increases. Desiring still more power from his 125, used in both flat-track and motocross events, Hamilton, also used road-racer porting and rotary-valve timing. Hamilton, however, incorporated extreme factory road-race specifications; he estimates the power output of his modified motorcycles as being in excess of 32 horsepower. This was phenomenal power from a 125cc engine—especially a single-cylinder one—and was equally hard on the engine’s dynamic components. In due time it dawned on Hamilton that the regularity of twisted, broken crankshafts—brought about from careening around dirt tracks with the little engine screaming in excess of 12,000 rpm—negated any practical benefit from the extreme power. Within several years he removed the 125 Maico engine and replaced it with a 125 Yamaha engine—admittedly slower, but infinitely more reliable. Hamilton raced the hybrid Maico/Yamaha for years after, with great success.[1]

Engine lubrication for two-stroke engines is critical, and is often debated by riders. Schank used regular organic (non-synthetic) two-cycle oil, mixed at 24:1 (parts gas/oil). He feels to this day that non-synthetic oils, though relegated to primitive “back-in-the-day” status when compared to today’s advanced synthetic lubricants, provide perfectly adequate lubrication. He also contends that mixing at higher ratios—such as the 40:1 or leaner mixtures now recommended by synthetic oil producers—tends to develop crankshaft wear on two-strokes. On older iron-barrel Maicos, Schank mixed oil at a richer 20:1.

Schank’s other modifications to his 125s were minimal. Dry air filters were changed to wet, oiled filters. On the front end, he ensured that the forks had the new, longer-length damping rods. Schank notes that early Maicos from 1968 to 1971, and all the 125s through 1973, came equipped with the earlier rods, which yielded only six inches of travel. The later rods allowed a full seven inches or more of fork travel. No other modifications to the forks were made, and Schank used a home-brew fork fluid mixture of half ATF (automatic transmission fluid) and half Marvel Mystery Oil (a commercial lubricant reputed to have near-fantastic qualities). Schank concurs that the Maico factory would have used up all existing parts before fitting newly-designed ones, where possible, and the lower-performing and less profitable 125s would have been natural recipients. “You know, they made so many of these parts and they just used ‘em up. They probably said, ‘Those 125 guys won’t know the difference!’”

Schank addressed the under-performing Maico front brakes by often replacing the whole wheel with a Yamaha unit. He believes the reason for the lack of stopping ability was one of excessively-hard lining compound in the Maico brakes. Maico parts creator and marketer Greg Smith would eventually discover another reason: that the drums and shoes were bored out-of-true during manufacture. Later, after Schank noticed long-travel suspension on Maicos being raced in Canada, during the 1973 Trans-AMA series, he began to modify his rear suspensions as well. He performed at least 20 of these modifications to his and friends’ motorcycles.

125 model differences

The exterior and interior case dimensions of the five-speed and six-speed 125 engines are identical, as are the bearings. And, six-speed gear clusters will fit, in older five-speed cases. This procedure requires fitting the six-speed shifting mechanism and shift shaft. All five-speed cases and the very-early six-speed cases were a heavier sand-cast aluminum—a laborious, costly procedure. Later cases were a more easily-produced die-cast aluminum. In 1973 Maico changed the shift pull-key (the part which locks the rotating gears) from a “straight-across” design to a cross-shaped key. This later key makes for a more robust shifting mechanism.

I asked about the presence of the numerals “1-2-5” on some 125 Maico forks. Schank responded that he was not aware of any such markings, in his experience. He has seen varied numerals such as “1-2-3” or “1-2-4” on upper and lower aluminum fork clamps, but recalls this marking being a confirmation of simultaneous line-boring at the factory, to indicate matching units.[2]

Maico frames are generally identical across all models. The only major differences between 125s and larger Maico chassis are the locations of the motor mounts and the rear wheel design. Prior to the 1977 Adolf Weil (AW) model series, frame dimensions and tubing diameters among all off-road Maicos are absolutely the same, despite a common belief that 125s utilized lighter-weight tubing. Beginning in 1977, though, according to Schank, Maico 125s do incorporate slightly thinner diameter tubing. This practice is believed to have been followed through 1983. The factory used the 1950s-era symmetrical rear hub with cush-drive assembly until 1975, when a conical, non-cush rear hub was incorporated on the 125 Maico. These conical hubs differ in size from those on the larger Maicos, but use the same brake linings as are used in front Maico conical hubs.

Engine outer cases were redesigned with more streamlined contours in 1972. A larger aluminum access plate replaced the small steel plate on the left (points and timing) side, with the right side being given a form-fitting case. Both sides feature the “MAICO” imprint.

The 125 Maico received radial-style cooling fins on the cylinder and head in 1974. With the introduction of the redesigned Maicos of 1976-1977 (the Adolf Weil, or “AW Replica” line, although 1976 models were not yet referred to as AWs), the 125 engine was likewise refined. The carburetor was removed from under the right outer case and mounted outside the engine on an alloy tube. This allowed the carburetor to be serviced and adjusted without removing either the outer case or the carburetor itself, when altering jetting. Another modification incorporated into the 125 that year was the replacement of the old “adjustable” ball-type crankshaft bearing with a roller bearing, similar in design to the larger Maicos.

The earliest (1968) 125 Maicos came with the original small fiberglass tank finished in blue, according to Schank. Aluminum-alloy fenders were used, along with the black ABS-type plastic air-box. In subsequent years, paintwork and fender/air-box material followed that used in the rest of the Maico line.

The mystery of the 125 Maico

Schank provided several observations and conjectures about the acquisition and fate of many of the 125 Maicos. “I found that after a 125 Maico sat on the showroom floor for a couple of years, you didn’t have to pay the suggested retail price. The 125s didn’t sell well . . . and the dealer would want to get rid of them. The suggested retail price on a 125 Maico was $1000. You could buy a Kawasaki for $650—that was about the price difference. And the 125 really wasn’t that much less than the 250 or 400 Maicos; the 400 was usually $50 more than the 250, and the 250 was $75 or $100 more than the 125. . . Basically, everybody who was buying one, was buying one for their fifteen- or sixteen-year-old, and buying a 400 for themselves. Most of the 125 riders were younger. Perhaps they weren’t as careful. I’ve seen kids destroy one in a weekend. . . .The rest of [ the 125s I bought] were used ones with the engine problem; mostly the transmission linkage. One had been disassembled for more than 20 years.”

These observations convey some interesting insights. First, Schank brings out a universal fact in motorcycle marketing: a smaller-capacity motorcycle is not necessarily any cheaper to manufacture than a larger-capacity one, but the consumer still expects to pay less for the smaller-capacity, lesser performing machine. Thus the 125 Maico—which, given its complex engine and lower production figures, may have actually been more expensive to build than the larger-capacity machines—still had to sell for less than these larger bikes. The product was thereby forced to carry a lower retail price tag than all the larger Maico motorcycles—but still at a price that ensured profitability—even as ever-higher-quality and far less expensive Japanese motorcycles caught the consumer’s eye. Schank further notes that 125s tended to be owned by younger riders. These young men likely had the machines purchased for them, and maybe felt less personal responsibility for the motorcycles. Thus, we might assume, these younger riders would have also been less likely to properly maintain a motorcycle or ride it in a manner that would have preserved it (and we all know that a Maico absolutely needed maintenance, between rides). We could thus expect this situation to result in more of these motorcycles being put out of operation, earlier in their service life.

Lastly, we see from Schank’s statement that many of the 125s he purchased were non-running machines, likely incapacitated by the common transmission problems. In terms of the preservation of such a rare machine, this design weakness may have actually helped to leave Maico 125s to posterity. Occasionally, mechanical devices of high cost will incorporate a mechanical weakness in a sub-system which can prematurely incapacitate the entire machine. This early failure may put the device out of commission before the overall item is considered worn out by the owner—as we might imagine in the case of a Maico 125 which would not shift gears. The problem may have been too expensive to fix or too annoying for the owner to continue regularly riding the bike. For various reasons, dysfunctional high-end machines, like the example of a relatively new but troublesome 125 Maico, tend to be retained by owners while cheaper machines are discarded. The reasons for owners’ retention of old industrial objects vary, but might include the initial cost of the item (such as an expensive motorcycle or watch); perceived future value, including both financial worth and utility of the item (such as guns and old tools); aesthetic qualities (attractive objects), and the relative ease of storage (such as a small item or a lightweight bicycle, easily hung in the rafters). An expensive, exotic, shiny-yellow but broken Maico 125 might thus have been more readily retained, shunted to the rear of a dusty garage or shed, but at least spared the junkman.[1]

When those owners elected to save an old motorcycle, did they then plan to ride it again someday? Or was the machine meant to be a trophy to some good times and former youth? Any broken motor vehicle can be brought back to life, with sufficient investment of time and money, and any competent motorcyclist of the day was enough of a mechanic to know this. Most likely, however, the motorcycle served the owner as a monument to his achievements and times then past. Like a mounted game animal, an old sports object, or a war trophy, the item is symbolic of the circumstances in which it and the owner were one. In the case of a motorcycle, the object likely recalls not only fun and competition, but also an element of danger, and the sacrifice and taste required to purchase a bike as expensive as a Maico. Most riders—usually not wealthy men—could not afford to keep their old motorcycles, and sold them in time to help finance their next mount. Whether proportionally more Maicos were saved by their owners than other makes is not known—though this does seem to be the case with other high-performance motorcycles.

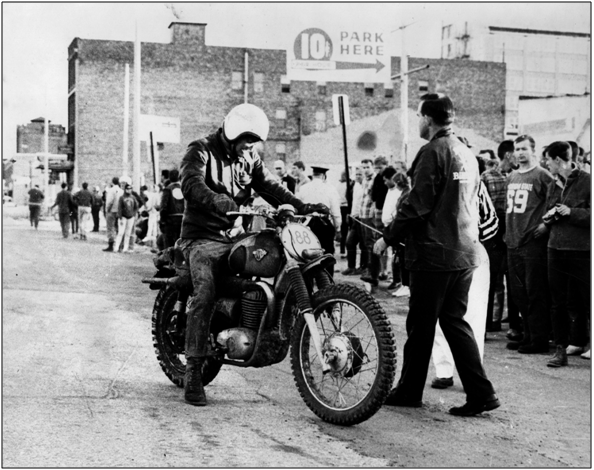

(Photo: Charles Schank)

[1] I once purchased a non-running Maico 125 from New York. The seller told me he got the bike from the family of two boys who never maintained the machine. When they smashed the stinger shut on the expansion chamber, one day, and it wouldn’t start, they simply pushed it into the barn and forgot about it. I thereby had a Maico with relatively low wear; simply one disabled by a problem the owners didn’t choose to deal with.

[1]Interview with Gig Hamilton by David Russell, November 14, 2013, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[2] A set of forks removed from a 125 Maico by the author in the 1990s had the numerals “1-2-5” stamped on the alloy fork sliders. While the assumption that the numerals were applied at the factory to mark 125 units—perhaps using up stocks of older, shorter-travel internal parts—is a reasonable assumption, Schank’s recollection suggests that Maico historians should stop short of designating this assumption as a fact.

[1] Adding length to the header pipe is a traditional method for improving low-rpm performance (while decreasing high-rpm power output)in two-stroke engines.

I own a 77 Maico MC125 and virtually no parts interchange with my larger Maicos of a similar vintage, the gas tank , frame and hubs are all different, the gas tank being much narrower.

Yes, that one’s REALLY different, Carl. I don’t currently have one, but was told that the frame tubing is indeed slightly lighter gauge, though the same geometry as the other bikes. And Maico tanks are always a mystery.

I have a late 60`s complete but rough. I would like to find a new home for this machine. Too many other projects. knobbyridge @aol.com. Maico`s storied history has always been interesting.

I raced in Northwest Illinois all through the 70’s and I only remember once seeing a 125. Tons of other Maico’s, including mine. Raced the first generation KX 250 for a local shop and against a 4-forker Harley. Looking back we went through quite a time of experimenting. Bent and broke my fair share of attempts to go faster.

I saw a four forker at Red Bud ,where the rider got his leg caught in the rear fork leg and the tire. They had unbolt the shock to get him un stuck. I am from South Bend and my neighbor was Howard Miller, who raced in 250 A with a 74 Macio and then got a 75 that had a lot of tranny problems . You might remember him ?He started racing motocross at 39 within one year he was a contender in 250 A ,and was a freight train comin through the woods in HS. I was 13 and raced 100 class from 74 through 76 . Raced all year in Hare Scrambles . Howard was state champ a couple of years in HS.I aced Red Bud , Lakeville, North Webster , K&R ,Gary Stroud’s racetrack . I think I only saw 1 125 Maico in my whole motocross experience. I bet they are big money now . I had a 1972 Yamaha mini enduro . Brand new $299 now, $5500 plus . My 74 TM 100 was just under $600.00 when motocross was affordable to most

What about the 1979 maico 125?

I myself can’t speak as to how incredible these little machines were as I rode/raced Rickman’s & Pentons in the early 70’s but I did occasionally see a rear tire of one in the 125 class?

Haha! Well, it must have been a Maico 125 that was still shifting & running, Paul–so that’s good!

I have had the pleasure to ride one what a piece,later on in years I became a factory maico mechanic for my brother Carlos Serrano on the 250US Nationals truly refined bikes by then,any way you put it the maicos,were worth every penny they cost.

Marti, would love to hear more about the bike you maintained for your brother. What year was that? What were the more challenging aspects of keeping a 250 competitive? Thanks! Dave

Great article! Thanks for posting! I have what I believe to be an early modified frame 125 Maico. It has a square barrel motor and the frame is in a GP design. I believe it’s an early frame modification kit possibly? I’m trying to research my motor and frame; however, I can’t find any reference to any early, if not all, Maico 125 engine serial number or frame serial number information. Any help or direction would be greatly appreciated. Thanks again, Mike