No products in the cart.

motorcycle resstoration, Uncategorized

Preservation and Restoration Part 1

Motorcycles as Artifacts

In the course of this article installment I have used the Maico motorcycle as the lens through which American sport motorcycle culture was examined. Now, looking back to this motorcycle—material culture, art object, utilitarian racing machine, or however else we may wish to think of it—what are we now to do with it? There are many Maico motorcycles in the United States, most held by collectors. We know these have value historically, culturally, and as a monetary commodity; but, how does an owner best maintain and extract that value? This chapter will examine the maintenance of these machines in several applications, and suggest potential courses of action for owners.

What will be done with the motorcycle/artifact is largely dependent upon what its use will be. Traditionally, in the case of artifacts, be they art, devices, applied arts, or adornment, historians and collectors understood the role of the item to be one of display; the “museum piece.”[1] These items were cleaned up, put on display in the public space or at home, and made available for further study or enjoyment. The artifact was then ready to perform its function of telling a story, being beautiful, or both. Considering devices (tools or weapons, for example), the object was probably not actually used again for its originally intended purpose. The thought of re-using a stone axe or bow-and-arrow from antiquity was an anathema to the owner/curator; it would break and thus be useless.

The advent of rugged or industrial items—machine-made tools, motor vehicles, or even homes—brings a reconsideration of potential function. These objects can perhaps be used again as they were originally intended, and in doing so, enhance understanding. An old Victorola can play records just the way it did for our grandparents, so that we can enter their aural experience; an old coffee-grinder can still grind beans with the smell and feel of decades past; and the antique automobile can still carry passengers. These devices, in continued use, help to convey a glimpse into their eras, surpassing or at least supplanting what we read in books. The owners of antique automobiles and motorcycles, in particular, often desire to use these devices for their own enjoyment, and not simply exhibit them. This re-use of vehicles presents new considerations for owners, which I will address after a short introduction of the idea of the “antique.”

The creation of “antiques” in the United States

The very idea that old items have any value at all is a fairly new concept in the United States. Americans from the first defined themselves by their very newness; an “indifference to tradition” and a rejection of those confines of their history which served only to remind them of their humble or precarious pasts, in the servitude of European (or other) overlords.[2] For most inhabitants of this country from the late 1600s to the mid-1800s, to place any loving notions on old stuff was preposterous; America was a land on the cusp of a new age, and romanticizing the old was not done for the first two centuries of our nation’s history. Moreover, as Tocqueville noted, Americans were tinkerers, always eager to improve and better adapt the implements with which they worked.[3] This fondness for innovation meant that older items, instead of representing the best version of a device, were seen as antiquated and inferior to newer ones.

In the years immediately following the Civil War, some Americans began to embrace a new (and healing) identity: “post-war pluralism,” as Michael Kammen labels the idea, created a need for a common culture and a collective memory. The United States did, leaders decided, have its own unique rich history and culture. And, they felt, it was a fresh, forward-thinking culture at least the equal of the tired European past; even superior to it. The country possessed a heritage, that once identified and celebrated, would serve to unify the more settled multicultural American sectional identities with the various other heterogeneous elements—not to mention the new waves of immigrants still coming. And our things would be part of this new cultural appreciation, helping to identify and locate this rich American past and giving the country a unifying cultural armature around which to come together.[4]

This newfound appreciation of American antiques flourished in the post Civil War decades. First Lady Grace Coolidge furnished parts of the White House with native antiques in 1902. In 1909 the Metropolitan Museum presented its first curated exhibit of American antiquities, opening its American Wing in 1924. With a major American museum now “legitimizing” the collecting of a specific item of material culture (a practice I will soon address, with special reference to the Guggenheim Museum) the American antiques movement was off and running. Antiquities, formerly the “old stuff” and detritus of American farmsteads and homes, were soon being sold by northeastern dealers to energetic collectors. The items usually fell into one of two categories. Briann Greenfield describes these two as either “historical” antiques, or as “aesthetic” antiques.[5] Historical antiques were important to owners and collectors for their historic content: Andrew Jackson’s quill pen, a musket used in the American Revolution, one’s mother’s comb set. The drawback to historical antiques was that there were only so many historically-significant items in a sea of other old things; furthermore, proving provenance to a buyer was problematic, at best. Aesthetic antiques, on the other hand, were valued for their visual qualities. This was something far easier for antiques dealers to assess, made saleable items vastly more plentiful, and further provided the buyer with a “promise of permanency”[6] (of value) for their purchase. Buyers could assemble collections of aesthetically-selected furniture, flintlock rifles, and pottery; categorized by maker, geographical area, or style.

Sellers and buyers of antiques soon had decisions to make, as to the care of their artifacts. Should a faded or worn old chest be repainted or re-varnished? Should broken parts be repaired? In many instances a case could be made that the aesthetics of an item would be better appreciated if it was refinished to as-new condition. Yet, the attraction of originality was also a strong incentive. There would be, ultimately, no absolute answers to these questions, and the same questions continue to be asked. For the collectors of antique furniture and other wooden items, though, there tended to not be a rush to refinish. The knowledge that the gleam of an old armchair may have taken one-hundred years to be burnished or faded the way it was, invited caution.

Motor vehicles as antiques, and the eventual debate over restoration

At the precisely the same time as these “traditional” antiques were garnering interest, the automotive industry had taken flight. As more vehicles were produced, the older motor vehicles, still retaining real or potential utility, like an old gun or tool, were often set aside, but not discarded. By the 1930s, these surviving early automobiles were technologically far-removed from the relatively advanced, aerodynamic, V-8 powered cars of the 1930s, and were being rescued by mechanically- and historically-minded enthusiasts. In 1935, the Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) was formed. Old motorcycles were likewise kept around and tinkered with, and the Antique Motorcycle Club of America (AMCA) incorporated two decades later, in 1954.

At the precisely the same time as these “traditional” antiques were garnering interest, the automotive industry had taken flight. As more vehicles were produced, the older motor vehicles, still retaining real or potential utility, like an old gun or tool, were often set aside, but not discarded. By the 1930s, these surviving early automobiles were technologically far-removed from the relatively advanced, aerodynamic, V-8 powered cars of the 1930s, and were being rescued by mechanically- and historically-minded enthusiasts. In 1935, the Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) was formed. Old motorcycles were likewise kept around and tinkered with, and the Antique Motorcycle Club of America (AMCA) incorporated two decades later, in 1954.

(Before continuing, it is necessary to define two terms, as they relate to antiques. To “preserve” is understood as retaining, as much as possible, the original features, coatings, and condition of the item or vehicle. To “restore” is understood as returning the vehicle to the state of condition it was in, when new.[7])

The founders of both the AACA and the AMCA avowed their purposes as being the preservation (in a general sense), continued operation, and enjoyment of the great vehicles of yesteryear. Members devoted themselves to keeping old cars and motorcycles around and running.  They organized “field meets” where they could enjoy the company of other hobbyists, share techniques and swap parts, and examine their fellows’ workmanship. In due course, both clubs established competition show programs and rules for the judging of old vehicles. These vehicles were separated into two major categories: original condition (preserved) and restored. To restore was the natural inclination from the beginning. After all, there were plenty of the old machines (cars, in particular) around, and who would not prefer a new-looking old car or motorcycle to one showing its age? One writer captures the simple, primal inclination to restore, when he states “Enormous pleasure can be gained by turning what appears to be an unattractive piece of junk into a beautiful antique.”[8] A machine operated in public was thus much more likely to be re-painted. “Like new” was good. The appreciation of natural ageing and “patina” in industrial (automotive and motorcycle) finishes had yet to achieve the level of sensitivity of the other antiquities movements, most notably the furniture collectors.

They organized “field meets” where they could enjoy the company of other hobbyists, share techniques and swap parts, and examine their fellows’ workmanship. In due course, both clubs established competition show programs and rules for the judging of old vehicles. These vehicles were separated into two major categories: original condition (preserved) and restored. To restore was the natural inclination from the beginning. After all, there were plenty of the old machines (cars, in particular) around, and who would not prefer a new-looking old car or motorcycle to one showing its age? One writer captures the simple, primal inclination to restore, when he states “Enormous pleasure can be gained by turning what appears to be an unattractive piece of junk into a beautiful antique.”[8] A machine operated in public was thus much more likely to be re-painted. “Like new” was good. The appreciation of natural ageing and “patina” in industrial (automotive and motorcycle) finishes had yet to achieve the level of sensitivity of the other antiquities movements, most notably the furniture collectors.

As time passed and original machines became scarce, the acceptance and appreciation of un-restored and unmolested vehicles evolved, echoing that of the antiques movement in general. As fewer and fewer vehicles with their original finishes were available for purchase (and to serve as examples), the vintage enthusiasts further reappraised their rush to restore. At present, both the AACA and AMCA highly value originality, and urge members to consider this option when contemplating the rejuvenation of a vehicle. The AACA strengthened its encouragement for members to consider preservation over the powerful inclination to restore, creating in 1979 the “Preservation” class. In this judging class, the cars can be driven and receive awards, while not being denigrated for incidental road wear and tear. Since there were fewer motorcycles made than cars in the United States, motorcycle collectors confronted the problem of scarcity of original antique machines earlier. To their credit, antique motorcycle owners embraced preservation (over the immediate impulse to restore) years before than their car brethren. To place the antique motorcycle community’s collective attitude in context, it is interesting to note that original antique American motorcycles in 2014 are often valued at two or three times that of a precisely restored similar machine.[9] The AMCA, for its part, notes in the “A Final Word” postscript to the AMCA Judging Manual, that:

“The AMCA judging system emphasizes the importance of keeping original motorcycles as such. These are truly the rare and priceless jewels of any collector, for they maintain and show with clarity and without any doubt, the true picture. When these all important machines are sacrificed unnecessarily to restoration, we have experienced a tragic loss. Therefore the AMCA strongly encourages the preservation and judging of original condition motorcycles.”[10]

The Motorcycle as Art

Thus, we can see, most motorcycle collectors agree that, given a vehicle in reasonably-sound mechanical and cosmetic condition, it would be generally preferable to not erase the vehicle’s patina forever, and to bequeath it to coming generations as a preserved, un-restored and original artifact. Yet this is not the end of discussion on the issue. The waters were again muddied in the early 1990s, with an acknowledgement by museum curators and commentators around the world: the motorcycle can be “art.”

Many motor vehicle collectors had for decades had no problem with internally considering the automobile or motorcycle as art, and not just artifact. Outside the circle of collectors, however, this was not a universally-held elite view. The vehicle-as-art proponents did have a good case. Ornate, ornamented or simply beautiful functional objects (weapons, armor, table services, and the like) had long been accepted in general history museums and some art museums prior to the industrial age. These objects, however, were hand-produced.[11] The advent of the industrial age and mass- and factory-produced objects involved different processes than the traditional hand-made, artisan techniques that had characterized the making of things since the beginning of history. As industrial manufacturing merged with major design movements in the early 1900s, art museums such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited industrial objects and design, granting legitimacy to those who believed useful objects could also constitute art.

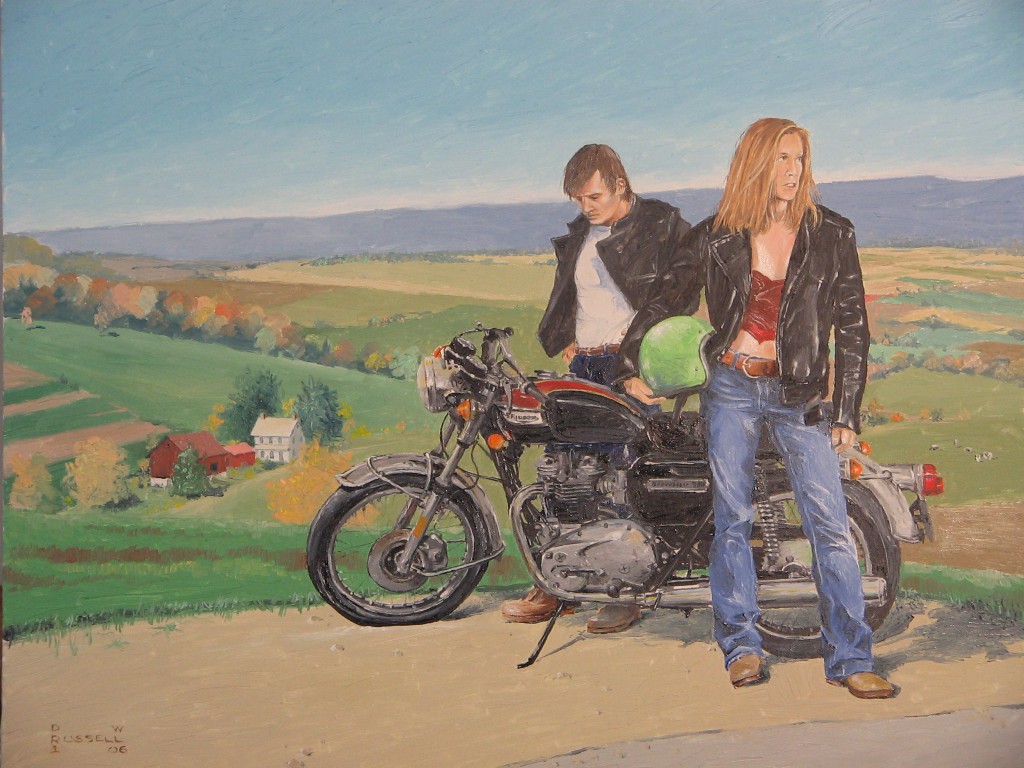

Art is described in dictionaries along the lines of the “quality, production, expression or realm of what is beautiful.” Classic representational visual art had, traditionally, two aims. First, it aimed to synthesize or reinterpret natural beauty (or, those aesthetics occurring in nature); this being inherent in the work’s composition, form, line, color, and skill of execution. Secondly, good art expressed an idea; that is, it conveyed meaning. Focusing on the motorcycle as industrial art object, I wrote in 1994 that, in reference to the quest for the beautiful, “The motorcycle is a symphony; a wonderful mural of line, shape and form embellished with color and texture. . . . The design of the carburetor; the glimmer of brass against alloy, of rubber against steel . . . The way the lines of the gas tank picked up the silhouette of the engine finning; the way each little cure and corner and edge and shape seem so perfectly designed . . .”[12] In regards to meaning, of course, the motorcycle’s suggestions of power, freedom, speed, and sexuality are noted here and elsewhere. Also, if interested, please view The Vintage Motor Company’s preview article, “The Motorcycle as Art”.

“Industrial art” had begun to be accepted as such for several decades, when the Guggenheim Museum began planning in 1991 to produce an exhibit of purely motorcycles, from an aesthetic perspective. This aesthetic emphasis was critical to the Guggenheim’s plan, as previous exhibits of industrial objects had tended to arrange the artifacts as part of a technological progression, emphasizing engineering lineage and importance first, and aesthetic aspects second. Taking an industrial object out of its usual home in the history/technology museum as the Guggenheim curators did, and placing it with a whole lot of its peers, stressing aesthetics in an art museum, was not looked upon favorably by some. Both motorcycle historians (who still felt that technological progression should be the primary unifying concept) and art critics (who were suspect of the subject, the curators, and, it seems, the presumed gruffly-attired attendees) had reservations. Typical of the latter was New York critic Hilton Kramer. According to the Wall Street Journal, Kramer decried the soon-to-open exhibit as a “bald-faced ploy to bring in money and whatever attendance might come rolling in on motorcycles.”[13]

“Industrial art” had begun to be accepted as such for several decades, when the Guggenheim Museum began planning in 1991 to produce an exhibit of purely motorcycles, from an aesthetic perspective. This aesthetic emphasis was critical to the Guggenheim’s plan, as previous exhibits of industrial objects had tended to arrange the artifacts as part of a technological progression, emphasizing engineering lineage and importance first, and aesthetic aspects second. Taking an industrial object out of its usual home in the history/technology museum as the Guggenheim curators did, and placing it with a whole lot of its peers, stressing aesthetics in an art museum, was not looked upon favorably by some. Both motorcycle historians (who still felt that technological progression should be the primary unifying concept) and art critics (who were suspect of the subject, the curators, and, it seems, the presumed gruffly-attired attendees) had reservations. Typical of the latter was New York critic Hilton Kramer. According to the Wall Street Journal, Kramer decried the soon-to-open exhibit as a “bald-faced ploy to bring in money and whatever attendance might come rolling in on motorcycles.”[13]

The curators at the Guggenheim were soon vindicated by, at the least, sheer popular approval. The museum’s Art of the Motorcycle exhibit broke all previous attendance records, was praised by most critics, and re-wrote the guidelines for exhibits of “industrial art.” Ignoring both the motor technologists and many art critics, the museum set an entirely new precedent for what an art exhibit could be. And, as the Metropolitan Museum had done in 1909 with its exhibit and “legitimization” of antique American furniture as art, so had the Guggenheim now legitimized the motorcycle as art.

The difficulty that this overall very positive turn of events presents (from our prior discussion of whether to preserve or restore, for more historical reasons), is that an art object is usually better viewed and appreciated in excellent condition, as when the artist/builder finished with it. Reviewing the Guggenheim’s catalog of 114 displayed motorcycles, we see that only a few are un-restored, and even these are in absolutely excellent condition. Motor museums tend to prefer to display restored machines; as a past curator of several motorcycle exhibits at the national AACA museum, I can attest that museum staffs often must be gently persuaded to allow the display of un-restored machines, in less than very-fine condition (as was the case with a rough Triumph “bobber” in the AACA Museum’s British Invasion exhibit of 2013).

[1] Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1982), 1-19. Prown places artifacts into one of five categories; those four listed here, with modifications to the landscape being the fifth. This categorization is basically in line with the breakdowns given by other material culture authorities, into which human material creations can be placed.

[2] Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 40-52.

[3] Alexis de Tocquville, Democracy in America (New York: Bantam Dell, 2004), 366.

[4] Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory, 106-45

[5] Briann Greenfield, Out of the Attic: Inventing Antiques in Twentieth-Century New England (Boston: The University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), 5-6.

[6] Ibid, 25.

[7] The AMCA describes “restored” condition as that of the vehicle on the “dealer’s showroom floor.” This description provides a small bit of allowance for wear (from transit), as compared to the seemingly obvious conditional description: “as new.”

[8] Albert Jackson and David Day, The Antiques Care & Repair Handbook (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), 6.

[9] Conversations between the author and Indian motorcycle owners at the Indian Nation motorcycle exhibit at the AACA Museum, Hershey, Pennsylvania, 2014.

[10] Antique Motorcycle Club of America, AMCA Handbook of Judging (Antique Motorcycle Club of America, Inc., 2010), 23.

[11] Many of the device-objects traditionally displayed by museums were celebrated for their ornamentation, however, and not necessarily for a singular aesthetic design.

[12] David Russell, “The Motorcycle as Art.” Classic Cycle Review, Vol. 3, No. 4 (1994), 17-19.

[13] Eileen Kinsella, “Guggenheim in Rare Tie-In With BMW for Bike Show,” The Wall Street Journal, May 22, 1998.