No products in the cart.

Uncategorized, vintage handlebar grips

A Short History of Motorcycle Handlebar Grips

In the beginning

The covering of the end of a motorcycle’s handlebar, allowing the rider to “grip” the metal bar and prevent his or her hands from slipping off, has been made of rubber and known by its function since motorcycling’s beginning.[1] The handlebar grips on early motorcycles were a rather hard natural rubber sheath. As motorcycles entered the second-hand market—and became the possessions of sometimes lesser-affluent owners or perhaps racers—home-made grips, built up by wrapping tape around the bar ends, appeared. Still, the basic original-equipment manufacturer (OEM) grip style remained standard for the first decades.

By the 1950s, manufacturers had added rubber material to the inboard end of the grip, helping to keep the rider’s hands from moving too far in that direction. Aside from this improvement, there seems to have been little change in grip design until the 1960s and the world-wide motorcycle “boom” (in sales) of the early 1970s.

Fig. 1. (L to R): Magura, double-wall street bike, Japanese “waffle” OEM, Magura-Doherty style hybrid, Petty “hex-grip”, Doherty-style copy, early Oury, Gold Belt soft rubber “Tacki-Grip” (Roger DeCoster signature), Camco latex rubber, OEM-style reverse-block.

Standard practices, circa 1960s and forward

As motorcycle riding and competition became more wide-spread, creative minds looked at ways of making the motorcycle a better conveyance. On both street bikes (which tended to vibrate and “buzz” through the handlebars) and off-road competition bikes (which exerted enormous stresses on the rider’s hands and forearms), motorcycle owners sensed that something could surely be done to improve this critical rider/machine interface. At the time, factory-provided grips fell into basically three types:[2]

- Thick, double-walled (hollow) grips for street bikes

- Thin, hard rubber (Magura-type) grips for dirt bikes

- “Waffle” grips on most Japanese bikes

While all three varieties functioned “good enough,” a close examination of the Japanese waffle grip offers us a micro-study of that growing industry, and why the first Japanese off-road motorcycles sometimes fell short. In the 1960s, the Japanese were beginning their conquest of the world motorcycle industry. They were expert copiers and made innovative, economical, and truly well-engineered products. In some ways, however, they still occasionally failed. For example, in theory, their “waffle grips”—fitted to all the Japanese dual-purpose motorcycles of the era—should have been perfect. The pattern held fast to the hand, the plastic would survive a bomb blast, and there was some element of cushioning. In testing over gentle trails by smaller Japanese test riders, the grips likely functioned innocuously and attracted no notice. When ridden hard, though, the grips caused blisters and proved tiring. One imagines the Japanese wondering just what was wrong with their foreign buyers—not understanding how to use their product! The Japanese, however, did soon recognize these and other shortcomings, even moving testing and research & development offices to the United States, where their key market lived and rode.

There must be a better way!

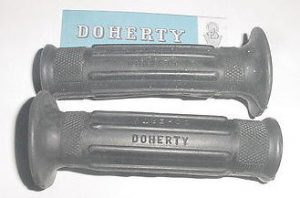

While early European motocross experts apparently used the thin, hard West German Magura and similar grips without issue, the “rest of us” tried different ideas, seeking to ease the cramped muscles, blisters, and torn skin. The first advance is said to be the English Doherty grip, which, in its sporting form, was a softer grip equipped with longitudinal ridges to help the rider hold on. In the early 1970s, aftermarket manufacturers experimented with other new shapes, among them the hexagon and other designs conforming to the shape of the clenched human palm and fingers—both intended to aid the hand in grasping the grip and reducing the muscle energy required of the rider to maintain control (American 1970s plastic bodywork innovator Preston Petty produced the “hex grip” shown in Fig. 1). Beyond shape, makers also experimented with softer compounds. These softer compounds sometimes resulted in grips that tore easily and had to be replaced every other race, but competitors did not seem to mind this. In the search for softer materials, one compound that saw service was one that many riders had seen—or would see, in the course of their predictable hospital visits—“surgical” latex rubber.

Natural latex rubber grips

Latex rubber is a substance made from (usually) rubber plants. While over 12,000 plants emit latex as a defense mechanism in response to physical damage, the latex produced by most of these plants is not conducive to the creation of commercial rubber. Natural rubber latex is non-vulcanized (that is, not heated and infused with sulfur, to create a harder and more durable rubber).[3] Latex rubber is known for its soft, somewhat viscous “stretchy” character—so much so that it is commonly used in surgical tubing, condoms, and slingshot bands. Having experienced this gummy natural latex rubber in other situations, motorcycle accessory manufactures suspected it might be a good material for grips.

And, the material was ideal for grips; its only drawbacks were a tendency to tear (like any soft rubber grip) and decomposition of some brands over time, from exposure to ultraviolet light and atmospheric gasses.

The Oury grip, made by the Oury Company (originally in Colorado, and still made in Imboden, Arkansas), was another step forward for grips. Oury grips were soft, impervious to light, the atmosphere and petrochemicals, and sold in a variety of jellybean colors. The original Oury grips were molded in a sort of “reverse brick” pattern—with the “mortar” between the “bricks” extended; modern Oury grips are molded with the “blocks” themselves extended.

1980s forward: the modern era

By the 1980s motorcycle manufacturers such as Honda had settled on a basic grip style, featuring a black rendition of the Oury reverse-block pattern. These OEM grips were soft enough, resistant to tearing, and performed very well, overall. This pattern (Honda’s CR grip is shown below) remains a very popular item.

Grips are currently made in a vast array of patterns, colors, and rubber combinations. Modern molding technologies further allow combinations of differing hardness and colors of rubber within the same grip. Street and dual-purpose motorcycles can even be equipped with electronically heated grips. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Husqvarna and accessories dealer Scott Fetterolf notes that, if he stocked all the styles his customers request, he would have more than 150 different styles in the shop! (He settles for about 30.)

Vintage Motor Tees invites you to experience a Blast from the Past by trying a pair of our original Camco latex rubber grips. These grips were recently discovered in a cache of period motorcycle accessories in a Midwestern warehouse. They have not deteriorated, and look and feel like the day they were made.

[1] “Grips” became the standard name for this item around the world. Owing to the throttle grip having a slightly larger-diameter hole then the grip fitting to just the handlebar, grips were also differentiated as “left” or “right,” and sometimes “throttle” or “dummy” grip (in the case of Austrian manufacturer Puch).

[2] Note: since this website primarily deals with off-road motorcycles, the majority of emphasis will be on off-road grips. As regards street bikes, suffice it to say that manufacturers and owners tried several ideas—among them softer, wider grips, made of everything from double-sided plastic to foam. Modern street bike grips are essentially the same as off-road grips, and use similar soft rubber compounds.

[3] This is the vulcanization process attributed to American Charles Goodyear in 1839, who used vulcanizing to make his rubber products more durable.

Insanely comprehensive 🙂

Thank you so much,

Now I have something to read during the holidays. This will take a while but well worth it like always

You can read another one here the motorbiker