No products in the cart.

motorcycle resstoration, Uncategorized

Motorcycle Preservation and Restoration Part 2.

MOTORCYCLE PRESERVATION AND RESTORATION

And so, given our discussion of the motor vehicle as both historical/industrial artifact and art object (our last article: Preservation and Restoration), what should we do with that old motorcycle in our possession? Preserve it for posterity, or restore it as art? In earlier times, contemplating simpler (non-industrial) objects, the task was less complicated: museum curators might simply pick the dirt and extraneous material out of the pores of a stone axe, catalog and label it nicely, and put it on display. But what of the more advanced, man-made object, the motorcycle? What of faded or missing paint and broken mechanical parts—should these be replaced? Is it “too nice to restore,” or must it be restored to be truly appreciated, aesthetically? If it is to be placed on display, is it necessary that the engine run? (And, is it the case, as a more radical element of the motorcycle collector community would have it, that it is a cultural crime to not run it?) Do we restore or not restore antique motorcycles, and should we ride a machine or not? Finally, how does an old dirt bike—like the Maico racing motorcycle—fit into this discussion?

‘Ride ‘em or Hide ‘em’: The same for all classic motorcycles?

The answers to these questions vary with a number of factors. Principally, these variables are: 1) the machine’s physical condition; 2) its rarity and/or value, and 3) its owner’s intended use of the motorcycle. With regards to operating the machine, we realize that a motocross bike was built primarily as an off-road and highly tuned competition motorcycle, and riding this type of motorcycle in the off-road environment is physically hard on both the rider and the motorcycle. Driving an antique car or street motorcycle in a parade, under ideal conditions, is one thing; it is quite another to ride an antique racing motorcycle in a competition environment, where some wear and damage to both motorcycle and rider is likely. The casual riding of a racing motorcycle is generally not practical. This is just a reality, and the same logic could be applied by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, if they were to respond to visitors asking, “Why don’t you take your 1950s jet fighters down from the ceiling and fly them more?” Fortunately, from a standpoint of historical context and “living history,” antique racing motorcycles can be appreciated in their intended environment at vintage racing events. At these meetings, specially-prepared versions of the antiques are ridden, with, we can presume, adequate reserves of spare OEM parts put away, and replaceable aftermarket parts installed where damage or wear is predictable (such as fenders, rims, and tires).

Conversely, if we’re considering the preservation or restoration of a street motorcycle—and the owner is a rider—it would seem silly to not preserve or restore it to riding condition, in most cases. Not only will riding your old Triumph in the annual Memorial Day Parade and harassing the Shriners in their miniature clown cars be fun, but it will allow many others to see that historic vehicle. (Note that I’m not suggesting it remain gassed and full of oil; just that the basics be done during the preservation/restoration process, when such major work is best accomplished.)

In the following pages I’ll be taking the reader through the preservation/restoration of an off-road motorcycle. Since the two courses of action are not entirely mutually-exclusive, I’ll discuss them both, together. (In fact, I suggest that even a “full restoration” often includes much that would more correctly be called preservation, as restoration implies a significant altering of deformities and existing surface finish. Restoration will include many surfaces and parts that are merely cleaned.) I’ll be using a Maico as the example—since I am most familiar with this area and many readers may be solely interested in Maico and/or dirt bike restoration—but will also bring street motorcycles into the narrative.

End use: What am I going to do with this thing?

The Maico is certainly an excellent vintage racing mount, if that becomes its intended purpose. Its handling and power continue to make it superior to its peers in such events. Replacement parts are available (though often expensive) and its peculiarities may be worth the extra enjoyment of riding a thoroughbred. Still, it is a Maico, and a Maico’s need of mechanical preparation and attention has not subsided in intervening years. Riding a Maico—and, really, just about any other old dirt bike—in vintage racing activities will require many maintenance-man-hours per riding hour, if the motorcycle is to be kept operational, safe, and competitive.

As I have mentioned, in regards to the riding of highly-tuned old racing motorcycles, the owner may choose to display, rather than ride, the finished motorcycle. Even if the decision has been made to not ride the motorcycle when complete, at least for the present time, the owner will still have to decide whether to preserve or restore (or some combination thereof). If the owner elects to preserve, he is not consigning himself to living with each and every fault or defect the machine begins with, indefinitely. As the AMCA encourages preservation-minded owners to do, broken and clearly worn-out parts may be successfully exchanged for appropriately-worn (but better condition) other parts, as the owner locates them. The fitting of superior used parts to a machine (to include fasteners) can produce over time a more visually-pleasing and operational preservation. Although obvious, a good cleaning (to include possible high-pressure water or even minimally-aggressive wet-media blasting) can work wonders in exposing the best visual qualities of the motorcycle. Modern metal preservatives, leather and plastic treatments, wax, and discrete polishing will also reveal hidden beauty.

Let’s get sensitive: Why you should love ‘patina’

Vintage motorcycle preservation and antique furniture preservation share much in the way we view paint remnants and surface patina. Antique furniture writer John T. Kirk believes that the surface of the antique often represents a “large part of the total personality” of the object, and again cautions that once paint is removed for the good intentions of a restoration, it is nonetheless “gone forever.”[1] This “personality” of a motorcycle’s surface finish—in the paint, its cracks, runs, the presence of over-painting or hand-writing, and its peculiar fading, discoloration, and changes; and in all other plating and metal finishes—are part of the visual history and tactile personality of the machine which cannot be replicated.

If possible, within the context of the owner’s plans for the motorcycle, good patina should be preserved. Wooden antiques, of course, have a great advantage over metal artifacts in that wood does not rust. Rust on metal, more accurately called oxidation (the corrosion resulting from the metal’s reaction with oxygen) must be halted to avoid eventual total substance breakdown. Furthermore, surfaces which are excessively oxidized may be either too weak or frankly so unattractive as to make restoration preferable in the eyes of the owner (as is the case with the above picture).

“When contemplating preservation of a vintage motorcycle, the degree of paint loss or damage and metal corrosion will often be the deciding factors in swaying the owner either way.”

Moderately damaged surfaces can often be surprisingly “brought back” from their present state with careful touch-up paint, keeping the best of the original surface’s patina while improving areas that are excessively damaged. Most every component on a motorcycle can be repaired, given requisite time and finances. Maico motorcycles in particular can be excellent candidates for preservation, owing to the factory’s use of fiberglass and aluminum. Fiberglass is easily repairable in the home shop, and takes paint easily. Aluminum, while probably requiring expert assistance to repair, responds well to repair and is less likely than ferrous materials to be badly corroded. Aluminum does, however, oxidize, and in the right circumstances will reduce to a powdery-white material.

Yeah, but it’s just too far gone: Reasons to Restore

Having described the positive reasons for preservation, I will now discuss restoration. Restoration should by no means be considered a dirty word, and it is routinely practiced by the most reputable owners, conservators and curators in the motor history world. Although restoration may carry a negative connotation in antique furniture circles, even the most ardently pro-preservation furniture conservators would concede that sometimes, even furniture must receive major repairs to be exhibited or be useful. Sometimes, the antique is just too far gone. (The “before” photo of Travis Agle’s square-barrel Maico at the intro to this essay adequately illustrates a motorcycle in this ‘too far gone’ state.) Curiously, the work of art restorers seems to not involve the any negativity, and we look at a “restored” painting as a positive thing. In fact, the traditional use of removable dammar varnishes to protect paintings reminds us of the idea that fine art is expected to require at least periodic manipulation by conservators.

The reasons to restore a motorcycle are, like preservation, many and laudable. One reason, as I have noted, is that technological/mechanical items are generally best viewed as art objects when in as-new or close-to-new condition. Art and technology museums generally prefer as-new machines to exhibit (but often have to content themselves with the fully restored). As-new machines best convey to the viewer the aesthetic intent of the designers, and also show exactly what the object looked like to its first owner. A clean, new-condition machine better allows the acquisition of information expected to take place by art/technology museum visitors, from the object. An examination of institutional restoration shops at The Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum, The Barber Museum, and any other technology museum confirms this practice. (History museums, conversely, convey other ideas, and might prefer a preserved example.)

Another valid reason for restoration is more a function of historical interpretation, and this is to be able to ride the machine (in essence, “re-enacting” with it). Using a motorcycle as it was intended (in the case of the Maico or other old off-road motorcycles, for off-road riding/racing) best conveys the sights, sounds and smells of the time.[2] Vintage competition in the past several decades, sponsored by the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) and local clubs has allowed onlookers and participants to experience and relive the great days of American off-road riding. Riders dressed in period attire—leather boots and pants, open-face helmets, and mouth guards—maximize the historical experience. This activity would not be possible without the restoration of these motorcycles; it is a rare old dirt bike that is operable, decades after its introduction, without needing major work.

Another benefit of restoration is the learning that takes place for the owner/restorer. For any restorer, conducting extensive work on the machine may be the best way to fully understand the motorcycle and extract its meaning. Just as beginning medical students spend their first year dissecting a body in order to understand human anatomy, the most comprehensive way for the motorcycle enthusiast to understand a motorcycle is to take it apart and re-assemble it. This protracted, demanding, often-frustrating, and intense process of repair and re-assembly is the opportunity for a unique and highly-personal learning experience. The restorer relives and imagines the machine’s meaning and history to the fullest and deepest extent. It is the mechanical equivalent of anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s admonition to look into a culture or activity in the deepest way possible; to seek “thick description” in order to arrive at real understanding.[3] While many enthusiasts are not capable of doing all the work themselves (for instance, boring a cylinder, truing a crankshaft, or reassembling a transmission), their oversight of such work, passed on to professionals, is the virtual equivalent to doing the work themselves. They will have forced themselves to fully understand these processes, whether doing them personally, or in conversation with the specialists and experts regarding work they cannot do. The level of understanding brought about by conducting a hands-on restoration far exceeds other means of learning about the motorcycle.

“Restoring a motorcycle is all about possibilities.”

Finally, conducting a restoration is simply fun. The fascination and enjoyment in seeing an object progress, as Jackson and Day describe, “from junk to beautiful” is an undeniable pleasure. The restorer is satisfied in an altruistic way, as well; he is “saving” an object for posterity, as well as seeing first-hand the transformation from rusty and dirty to clean and beautiful. He or she is filled with hope conferred by “possibilities.” Fred Haefele writes about this peculiar facet of the restorer’s motivations in Rebuilding the Indian. Haefele observed that, in the case of his antique motorcyclist friend Chaz, it was “the possibilities that move Chaz, not the fact [of his machine’s real and decrepit present condition]”[4] Restoring a motorcycle is all about possibilities, even if imagined, as we envision ourselves “wheelying into the sunset” on our rejuvenated, beautiful, one-of-a-kind creation, admired by all who look upon us.[5]

Getting started: General preparations for a restoration

First, arrange your work area. We don’t all have the advantage of a great garage, but you should attempt to locate a workspace with good lighting and some vertical storage. (Both these needs can met with an inexpensive trip to the hardware store. Buy a hanging fluorescent light and a metal storage shelving unit, if you don’t have them.) You’ll also want your work space to be a place that can remain undisturbed for the duration of the project, if possible; having your family pack and move your piles of parts to get to the washing machine is a sure way to lose things. Of course you’ll want the right tools as well. The basics include: a 6-point socket set including deep-well sockets and some extensions; a good, comprehensive screwdriver set; pliers; cushioned mallet; a couple adjustable wrenches; and a hand impact-driver.

Next, before you succumb to the temptation of taking your motorcycle apart, take digital reference pictures. Any picture is good when you’re in a bind about how something went together, but the beauty of a zillion digital images, on your laptop, beside you, and capable of being zoomed-into is something I’ve just recently enjoyed! Plus, digital is cheap. Take more pictures as you dig deeper into the disassembly and expose new, hidden areas.

“While you’re eagerly pulling off parts, you may think you’ll surely remember that the dark green wire, here, connects to the green and yellow wire, there . . . well, trust me that it’s best to write it down.”

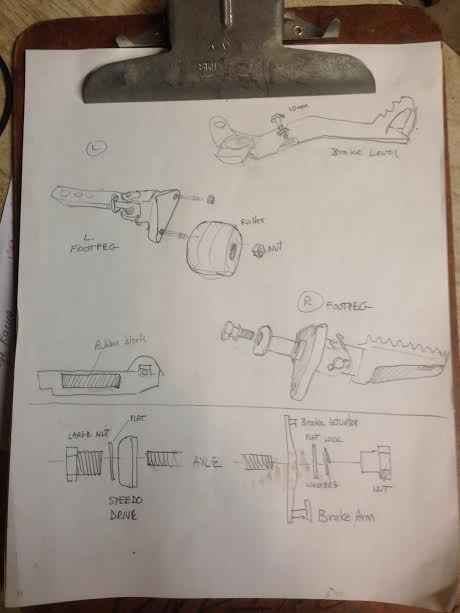

While we’re considering the advantages of being able to put it all back together again, using photos, remember to label extensively. I have masking tape and a pen standing by to note what connects to what, and also use clipboard & paper to draw how more complex assemblies go together (e.g., the sequence of spacers and washers on the front and rear axles). From my own experience, while you’re eagerly pulling off parts, you may think you’ll surely remember that the dark green wire, here, connects to the green and yellow wire, there . . . well, trust me that it’s best to write it down.

Whatever motorcycle you’re restoring, buy a manual. Whether an owner’s manual (like that provided with the bike, when new), a factory shop manual, or an aftermarket maintenance manual (such as those by Clymer or Haynes), such a reference is good to have.

Maico Restoration

Restoring a Maico motorcycle is not fundamentally different or more demanding than the restoration of any other brand. In fact, Maico restoration is often easier than some others, owing to the crudity of original factory surface finishes—assuming originality is desired versus the condition known as “over-restoration.” As previously mentioned, fiberglass parts are easily repaired and painted (unlike ABS-type plastic, which cannot easily be sanded to remove bumps, and can be difficult for paint to adhere to). An added bonus for the Maico restorer is that the original factory paint application was so mediocre (that is to say, crappy) that the restorer—or one looking for originality, at least—can nicely emulate original paint with a spray can in the back yard, if the correct color can be obtained.

Factory Maico paint often contained “bug’s eyes,” runs, and many other imperfections, so if the restorer is seeking an original look, a good facsimile is easily obtained in the home shop. Maico frame paint was likewise unremarkable and came in black and silver colors. Spraying a clear-coat on top of commercially available silver and aluminum colored paints gives a result very like the original silver frame paint used on Maicos and many other European dirt bikes. (Automotive-type non-acrylic paints, which are impervious to gasoline, should be used.)

Used OEM parts and newly manufactured replacement parts are currently available for most every detail on Maico and other classic racing motorcycles. Digital technology has made the reproduction of stickers and emblems an easy task as well, and what can’t by purchased commercially can often be reproduced quite satisfactorily by local sign makers. Restorers will need to make decisions about whether to seek OEM parts or use easier-to-obtain modern equivalents (especially in the case of “consumable” parts, like tires and chains). This choice is often finalized by the type of use the machine will see. Motorcycles placed in running use will benefit from modern (and often cheaper and better) tires, chains, and levers, while statically displayed art-object motorcycles may be more accurately interpreted by obtaining original equipment items (which are often too valuable to be placed in danger on a vintage competition machine, or may be too brittle or fragile to use reliably).

A requirement on most old Maicos will be the replacement or refurbishment of fork tubes. Maico tubes, for whatever reason, easily rusted and most are especially pitted in the exposed area, between the upper and lower triple-clamps. Fork tubes may be either re-chromed or replaced with new facsimile items; either option will be expensive. Defying the old stereotype of cheap Spanish steel versus high-quality German steel, Spanish fork tubes—such as on the Betor units common on Ossas, Montesas, and Bultacos—seem to never rust. Nor do Spanish spokes.

Another common problem with Maicos is that the swing-arm pivot bolt may be difficult to remove during disassembly. Lack of lubrication over time causes the pivot bolt to seize on the swing-arm inner metal sleeve, and it may be that no amount of hammering or heating will loosen the bolt. Access to a hydraulic press will be needed to extricate the bolt without bending the frame. (To prevent this happening again in the future, a Zerk-type grease fitting can be added to a swing-arm with minimal effort.)

Maico’s design for attaching the engine to the frame was somewhat under-engineered, especially for the bigger engines, and vibration would loosen the bolts and elongate the frame mounts and engine cases. The engine mounts on the frame and the engine case attachment areas will both likely require repair. When the engine is to be re-mounted into the frame (especially in the machine is to be run), the restorer should consider the use of American-made Grade-8 bolts. These high-strength hardware items—easy to recognize because of the “brassy” like plating—are less likely to vibrate free, are an authentic period upgrade, and will enhance the look of the motorcycle, whether it is to be ridden or not.

Fitting the engine back in the frame can be a headache, and in many cases it only goes in properly from one side or the other. You don’t want to discover this as you put another scratch on your previously beautiful, shiny black frame, or after you drop the engine—fragile fin side down—on the garage floor. Write down how it came out, or consult a manual for instructions on how to replace the engine. You may also want to use a hydraulic hoist or have a buddy to help you, for heavier engines (a twin-cylinder four-stroke, for example). Place rags on the frame to avoid scratching it as the engine is worked into position.

Test-fit any part that is custom-made or substantially repaired (like an exhaust pipe that’s been cut and re-welded) to make sure it fits before you have the parts painted.

“Buy yourself that hand tool called an impact driver . . . It will allow you to remove those butter-soft, stripped screws from your old motorcycle without getting so angry that you hurt somebody.”

Returning to the subject of fasteners, many period bikes used nuts & bolts which were inferior. Japanese motorcycle screws—always incorporating a Phillips bolt head that at least partially stripped the very first time you tried to remove it—were said to be “made of butter,” back in the day. Replace them with good quality American-made fasteners during your rebuild, and consider moving to Allen-head-type screws if the retained part is going to have to be removed often. Finally, remember to buy yourself that hand tool called an impact driver, mentioned earlier. It will allow you to remove those butter-soft, stripped screws from your old motorcycle without getting so angry that you hurt somebody.

The restorer should consider saving small metal pieces and having them cleaned and re-plated for future use. Some bolts and nuts are specific to the Maico and other machines, and not easily obtained, so the restorer would be wise to save and label all removed parts until positive they won’t be needed. Small fasteners, especially nuts, may not be re-usable even after re-plating, and comparable metric items can be purchased in local hardware stores. If the motorcycle is to be raced and presently has a fiberglass fuel tank, consider fitting an aluminum fuel tank or even using an aftermarket plastic tank. This will preclude an array of problems, notably breakdown of fiberglass resin and clogging of fuel filters and taps, and breakage/leakage of the fiberglass tank. Paint the old one and put it on your shelf as a decoration.

On other motorcycles with metal tanks, you may be able to have dents removed by specialists. If the tank is painted, dents are much easier to hide. If you’re painting yourself and not taking the tank (and anything else that gas touches, for that matter…like the frame), be sure to use gasoline-resistant engine paint. (You can buy this at automotive supply shops.)

Maico engine parts are likewise expensive. If the engine is to be restored and run, expert assistance during the rebuild will help insure that the engine operates properly and lasts; ruining hundreds of dollars worth of top end rebuild in the first few seconds of running, because you failed to fit the piston circlip correctly or put the rings in wrong is not fun. Maico engines are designed around precise tolerances, and proper shimming of the transmission gears is especially critical. As of this writing, Maico experts are still available to assist with engine restoration. I advise any restorer to obtain the assistance of such an expert, or at minimum a proficient motorcycle mechanic. The restorer of a motorcycle for display-only purposes may elect to delay or not restore the engine internal parts. I can’t say that this is wrong; if you just want to look at your piece of bike art, why spend $2,000 on an engine rebuild? However, if the owner plans to show the machine in AACA and AMCA competition, he should note that both organizations’ rulebooks require that a motorcycle engine be proven to run for several seconds before being permitted to be judged.

I can assure you that the slushy feel of a $250 kick lever destroying its splines, as it simultaneously reduces the splines on a $275 kicker gear to metal shavings, in one heavy stroke because I failed to tighten the ten cent bolt, is nothing I hope to relive. Check your work.

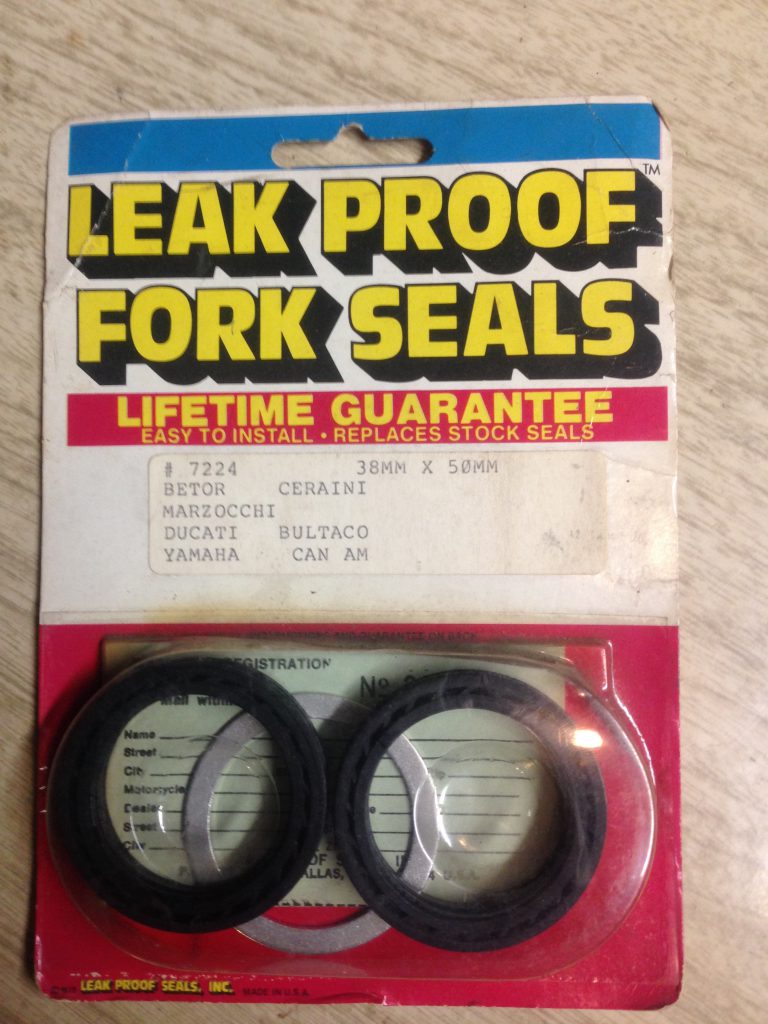

Maico primary-drive chains, endless twin- or triple-row industrial chains originally made by Renold of England, are not easily available from industrial suppliers, and will likely have to be purchased from Maico specialists. The restorer should beware of purchasing very old NOS rubber and fiber items (particularly seals and engine gaskets) as these items may harden and shrink over the years. Thus, buying your fork seals on eBay will probably get you a set of rock-hard, 20-year-old units that won’t do what they’re supposed to do. Individual gears for bikes that are to be ridden can be the hardest part to source, as they have not yet been remanufactured, and the only sources of replacement gears are the few remaining NOS items and from donor engines. An expert mechanic should review replacement gears for a motorcycle that will be ridden, as nearly-imperceptible wear can significantly affect operation. Maico kick-starter gears and levers were designed with extremely fine intermeshing splines, and these damage easily (if they are not already ruined). Before kicking-over an engine, the owner should ensure that the kicker lever is properly tightened on the kick-starter gear output shaft. (After attempting to start a 450 Maico I had for sale—to someone who was never really planning to buy it, anyway—I can assure you that the slushy feel of a $250 kick lever ruining its splines, as it simultaneously reduces the splines on a $275 kicker gear to metal shavings, in one heavy stroke because I failed to tighten the ten cent bolt, is nothing I hope to relive. Check your work.)

Rims and spokes on Maicos and other old motorcycles undergoing restoration will likely need to be replaced. If you plan to replace the rims using other used rims, ensure you match the angles of the holes exactly, as you don’t want the spokes to bend in the final assembly. Both new rims and spokes can be sourced through specialists, who in turn likely order from Buchanan’s Spoke & Rim in Azusa, California. Waldridge Motors in Ontario, Canada can source chrome OEM Radaelli chrome rims.

These, then, are the principal decisions facing the restorer: to preserve, to restore for static display, or to restore functionally, for use. Each choice has its valid points and will be best pursued in certain circumstances, after thorough consideration by the owner. The owner should enjoy the process in any case, knowing that something is being saved that is historical and beautiful.

Hey vintage bike fans, if you enjoyed the article, ‘like’ us on Facebook or leave a comment below. We’d really appreciate it!

[1] John T. Kirk, Early American Furniture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1979), 192.

[2] The unmistakable aroma of burnt pre-mixed natural oils in the old two-stroke engines is one aspect of creating the reminiscence of 1960s and 1970s motorcycle riding.

[3] Clifford Geertz. “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,” from The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 412-54.

[4] Fred Haefele, Rebuilding the Indian: A Memoir (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998), 134.

[5] David Richardson, email to the author, January 24, 2000.

Like you said, to restore a bike you would need to know all of the parts needed to make that bike. Because restoring a bike means that you are working with old parts, you would have to have a place to buy used bike parts. I know that a lot of salvage yards have older bikes and allow you to buy parts. It would be a good idea to check a salvage yard before starting a restoration project to make sure that you can get most if not all of the parts that you need.

That can certainly be a challenge on a more obscure machine. On the less obscure bikes–a Norton, a Triumph, Harleys, etc–most everything can be found from one source or another. A restoration yard would be great, though!

I AM CURRENTLY RESTORING A VINTAGE MAICO. LET ME TELL YOU THEY ARE A PAIN IN THE ASS!! EVERYTHING HAS TO BE EITHER SHIMMED TORQUED TO SPEC AND MEASURED FOR PROPER TOLERANCES. BEST BIKE FOR ME RESTORING WISE IS WAS A SUZUKI TM 400 CYCLONE. YOU COULD PUT THAT THING TOGETHER BACKWARDS IF THATS POSSIBLE AND IT WOULD STILL RUN. MAICOS WILL NOT RUN IF THE ENGINE CRANK AND TRANSMISSION IS NOT SHIMED AND TORQUED TO SPECS. MAICOS ARE EXTREMELY EXPENSIVE AND DIFFICULT TO BUY PARTS FOR.

Really like your stuff man, thanks for sharing

Thanks, Chris!

Really like your stuff, thanks for sharing