No products in the cart.

Maico

Like Nothing Before: The Maico 501, Part 1

“You don’t test a 501; it tests you.”[1]

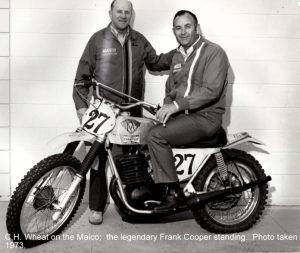

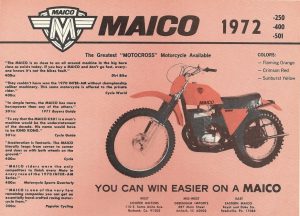

Maico was known as the company which made big-displacement motorcycles, the best. Though it produced smaller ones, it was Maico’s larger motorcycles that forged its reputation. During the company’s prime, as has been previously noted, over half the machines on the starting line of an American expert class motocross race in the 1970s were likely to be carrying “MAICO” decals. While the 400 was the standard for a decade, the 450 the “powerhouse of powerhouses when it appeared,”[2] and, later, the masterful 490 was the ideal of useable, perfect, massive power. But there was one more big Maico. In its day, the MC501 Maico—the “five-oh-one” in subculture parlance—was the largest single-cylinder, two-stroke-engined motorcycle ever made. Maico built the machine due to the urging of two imaginative Californians: Frank Cooper, the western United States Maico importer, and C.H. Wheat, a brilliant tuner, racer, and businessman.[3] That the company acted upon their suggestions reveals much about the communication and trust between the German and American ends of the Maico business, at least in the early days. At corporate headquarters, Maico knew the importance of their American market. On the other end, in the United States, dealers and racers justifiably felt a sense of ownership over their chosen motorcycle, and realized it when the Maico leaders and engineers were listening.

Why build a 501, anyway?

In American cross-country, scrambles, ice, and hill-climb competition events in the late 1960s, a “501cc to 750cc” class required motorcycles entered in this class to possess an engine displacement within this cubic-centimeter range.[4] The big British twins and singles, by virtue of being generally the only motorcycles having such a displacement, naturally dominated the class in these events. Cooper and Wheat were familiar with Maico’s superiority in every facet of off-road motorcycle design, and could plainly see that if Maico built a machine that met the displacement criteria, it would certainly outperform the old British Triumphs, Nortons, and BSAs—all of which had had cache in their era, but which had been stagnant for years. Cooper and Wheat also may have conceived of the machine as part promotional creation. These two master tuners, racers, and salesmen certainly had knowledge, earned through competition, behind their vision. Their expertise provided a basic idea to Maico of what this bike should be; a short-stroke, massive engine in the proven and strong Maico frame. The idea was novel and interesting, but the actual design and production would require significant resources from a small company like Maico. On the other hand, success on the track—and the faithful’s trust in Maico—was something the company took seriously.

Maico was in no way the exemplar of a company eagerly adopting user input—but nor were they the worst, either. Gunnar Lindstrom recalls Maico ace Adolf Weil complaining of Maico resisting the early 1960s trend towards light weight, yet they did eventually comply with the riders’ pleadings. Husqvarna, on the other hand, so resisted the implication that the company was anything but omniscient, that Lindstrom—a Husqvarna engineer—left the company in disgust in 1974.[5] Maico was not nearly as intransigent. And, considering their immediate integration of long-travel suspension into production (as will be discussed in later chapters), we can say that Maico was, for the most part, a company which did wisely listen to its riders.

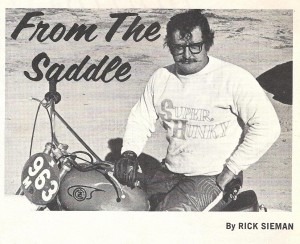

Any mention of the Maico 501 invariably traverses a path to another American motorcyclist: the equally iconic Rick “Super Hunky” Sieman. Author and Dirt Bike Magazine founder Rick Sieman is one of the most recognized and trusted—and often controversial—voices of the elder American off-road and vintage motorcycle community, and has not allowed Maico motorcycles or the 501 be forgotten. Sieman has certainly been the 501’s greatest cheerleader since the machine’s inception, and without him the motorcycle might now be just another unknown oddity. He retold the legend of the 501 many times, first in Dirt Bike—the magazine that serves as the text of record for the original off-road subculture—and later in other venues. Sieman promoted the 501’s mythic power and championed its reputation for decades, and his identification with the 501 is largely responsible for the enduring legend of the motorcycle. The man and the machine were certainly similar; both were unique and oversized in respect to their personalities, physical presence, and impact within the American sport motorcycling community.

(Photo: Rick Sieman and Dirt Bike Magazine)

The engineering challenges faced by Maico engineers in the design of the 501 centered on minimizing the weight of the large piston-and-rod rotating mass, in order to control the big engine’s vibration. German Maico accepted the challenge and set to work. Collaborating with the Mahle company—Maico’s regular piston supplier and also a supplier to Porsche—Maico designed a very wide 92 mm piston, running along a comparatively short 76 mm stroke. This “over-square” or “short-stroke” design—in which the bore is greater in diameter than the length of the stroke, differing from all previous Maico designs—allowed the desired 501cc (500.84 cc to be precise) displacement, permitted higher rpm, and kept excessive vibration and other potentially dangerous reactions in check. The massive connecting rod was necessarily heavy, but it was at least somewhat lighter than what it might have been, if the engine was of a longer stroke.

Early Maico 501s (did you say, “three-speed transmission?”)

The first 501s, occasionally called “505s” in the early press reports, to reach America in 1970 were especially unusual in that they possessed a three-speed transmission. When other large bikes used a four- or five-speed gearbox, and smaller machines might utilize a six- (and rarely, seven-) speed gearbox, the big Maico stood out. Yet, when a prototype was tested by Cycle Guide in 1970, there were no complaints; the machine produced so much power (“. . . absolutely staggering. It boggles the imagination. . . . [the] power output cannot truly be described.”) and was so capable of pulling any gear at low rpm, that the magazine’s testers pronounced the three-speed gearbox “more than adequate.”[6] This same magazine notes that most riders could not ride this early 501 in anything but first gear, and only a few very experienced riders could ride the thing wide-open in second gear. No-one, the writers noted, was able to hold the big Maico’s throttle open in third gear—a gear that was aspirational, at best. All the same, a three-speed gearbox had not been seen on a motorcycle since early in the twentieth century—everyone, it seemed, ‘knew’ that a motorcycle needed at least four gears. (Importer Dennie Moore stated that, after riding the 501, he believed that the machine could actually have coped with a single gear, if tuned accordingly. After all, if it did not need a first gear to start forward motion—second was easily able to do the job, and no rider could wind out third, anyway—the concept is not ridiculous.)[7] While a four-speed gearbox would be incorporated soon into all the actual production bikes exported to America, the early ‘so-powerful-it-barely-needs-gears’ story was a factor in the beginning of the Maico 501 legend.

So, where do we ride this thing?

While outfitted and nominally labeled as a motocross bike (MC), the 501 was not necessarily suited to an enclosed track, or even in longer-distance outdoor riding. Its power output, though never considered ‘pipey’ or still potentially explosive, and could be difficult to control in a motocross racing environment. Ridden by riders of varying skill levels, the 501 appeared to invariably take a few seconds longer to navigate around a motocross track than either the old, easier-to-handle 400 or the brutally-quick new 450. In fact, no top professional racer is known so far to have used the 501 in elite competition. Even consummate Swedish racer Ake Jonsson, certainly one of the most gifted racers in the history of motocross, preferred the more docile 400 to both the 501 and the 450. The motorcycle also inherited Maico’s annoying legacy of loosening motor mount bolts, a problem Sieman prominently noted, and one which could quickly ruin the expensive big engine.[8] Finally, the Maico 501 was, after all, a Maico, and that implied careful owner preventative maintenance and repair to keep a thoroughbred of this degree healthy and running.

The desert and long-distance rides tended not to be the 501’s ideal application, either. Consuming fuel at a prodigious rate (“like a Buick Riviera with a camper and six boats bolted to the back,” in Sieman’s words[9]), the big Maico’s range was limited to about fifty total miles, even with the largest available accessory gas tank fitted. Thus, the 501 would always be tethered to its fuel source. The motorcycle’s actual, historical use by a majority of owners appears to have been mostly that of a trail bike, surprisingly, where the rider could enjoy the incredible torque while staying close to the gas supply.

Super 501s

The one notable competition application for the 501 was its use in scrambles and dirt track racing, probably more what Cooper and Wheat had intended in the first place.[10] Here the big motorcycle shined, as did Maicos of all sizes. Rick Sieman notes that a specially-prepared twin-carbureted version was raced by C.H. Wheat and later by professional flat-tracker Danny Hockie in California events in the early 1970s. This version, Sieman recalled, employed two carburetors on a “Y” shaped manifold, together with changes to the frame to accommodate the large assembly. A smaller 28 or 30 mm carburetor controlled lower-rpm operation, while a bigger 44 mm carburetor began adding its fuel/air charge at about 5000 rpm. Sieman, comparing Wheat’s personal machine to his own slightly-modified 501 (which was at the time producing sixty-three horsepower at the countershaft sprocket) proclaimed that Wheat’s bike was so much more powerful that there was “no contest” when racing the two. Sieman guessed that Wheat’s bike must have been at least 20% stronger than his own, which suggests that the twin-carb bike may have been producing seventy-five horsepower, or more.[11]

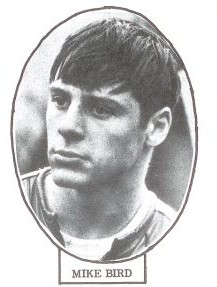

The whereabouts of C.H. Wheat’s machine are unknown, but a very similar machine was owned by former Eastern Maico distributor Dennie Moore until 2004, indicating that at least two twin-carb 501s existed. Moore recalls that a local flat-track star, Mike Bird from Bellefonte, Pennsylvania (Figure 31), campaigned a Maico 501 with some success. He and Moore felt, however, that the engine was dangerously starved for fuel when operating at maximum rpm, while flying down long straights in excess of 100 mph. Moore discussed the problem with Maico engineers in the fall of 1971.

The factory and Moore jointly conceived of the idea of experimenting with using the two carburetors, one small and one large, feeding the cylinder at low and high rpm ranges, and ensuring adequate fuel supply. Many months later, in early 1973, the experimental cylinder and manifold arrived at Eastern Maico in Reedsville, Pennsylvania, and Moore had a replacement frame altered to allow the additional room needed by the new head and “Y-mounted” carburetor intake set-up. 1973, however, would prove to be a tumultuous year personally for Moore and his business, and the partially-built motorcycle was set aside. Ultimately, the machine was never used or completed. Decades later, in 2004, this east coast 501 engine and frame were sold by Moore to Kentucky collector Cody Tellis. Whether the west coast twin-carbureted version was derived from Wheat’s invention, or whether it was solely the result of Moore and Bird’s prompting, remains unknown. For his part, Dennie Moore was unaware of the existence of the west coast machine until 2013. [12]

The production Maico 501

The 501 rolling chassis (frame, wheels, and suspension) is identical to other large-displacement period Maicos. Larger-capacity gas tanks were available as options, or were sometimes already fitted by wise dealers. The September 1971 Modern Cycle test 501 came equipped with a fiberglass or plastic oversized tank, which the authors said was a dealer option. Later 1974 501s—by this latter part of the production year also LTR-suspension models—are known to have been imported with larger alloy tanks, similar in form to the 1975-1977 alloy tanks, but of less capacity than the very-large “GS-style” alloy tanks of these years (see Figure 32). Other than the engine assembly and slightly increased weight, the basic 501 motorcycle is the same as the 250s, 400s, and 450s of that year. The engine itself is similar to other big-bore Maico units, but uses a different crankshaft and primary drive gear, cylinder, piston, and cylinder head. The exhaust system is the same as that used on the 400/450 engines. The standard original-bore 91.6 mm piston ran in a 76 mm stroke barely longer than the 70 mm stroke of the much smaller-capacity 250 engine. Whether the early stock engines produced forty-eight, fifty-two, or some other amount of horsepower at the countershaft, it was no trifling amount of power for a 243-pound motorcycle. Later engines, fitted with the easier-to-use but slippage-prone “large” clutch, were tuned to produce less power. The September, 1971, edition of Modern Cycle references Maico’s policy regarding the 501’s state of tune. Apparently, the magazine was informed that Maico had earlier decided to build two versions of the 501: one an “ultimate machine” producing fifty-four horsepower, and the other in a milder state of tune, producing forty-eight horsepower. According to this article, the factory ultimately backed away from this idea, and elected to build only the lower-horsepower, large-clutch version. But Maico didn’t abandon the high-horsepower idea entirely: Modern Cycle passed-on Maico’s promise that “owner’s manuals and bulletins” delivered with the 1971 501 would describe how the owner could, through some machining of the piston and cylinder, take the machine to the higher state of tune, if desired.[13] Rick Sieman likewise tells us that the first step in reviving the storied performance of the 501 is to return the engine to the these original factory porting specifications. This process involves removing several millimeters of metal from the piston, head, and exhaust pipe to increase gas flow.[14] Even greater power could be accessed through more aggressive porting; Sieman stated that his own 501 attained nearly sixty-three horsepower after this “second-stage” tuning. The moderately tuned variant was the mass-market edition of the 501, at least initially. Appearing in early 1971, this variant as tested by Modern Cycle was said to produce forty-eight horsepower at 7,000 rpm. A factory owner’s manual of several years later, in 1974, quotes fifty-one horsepower at 6,900 rpm; which figure was more accurate is open to speculation.[15] Fuel was metered, mixed and delivered by a very large 38 mm Bing carburetor, with the gasses ultimately being compressed to Maico’s standard 12:1 compression ratio with the piston at top dead center. Primary drive on the 501 was initially by double-row chain, upgraded soon after, along with the 400cc and 450cc bikes, to triple-row chain, beginning in 1972. As with most Maicos, a close- or wide-ratio gearbox could be specified by the buyer. In actuality, however, most buyers probably purchased the more commonly-shipped close-ratio motorcycles for general riding and motocross.

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here. It also just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

[1] Rick Sieman, “Maico’s Earthquake Machine.” Dirt Bike Magazine (April, 1973), pp. 42-46.

[2] Motocross Action, “Race Test: Maico 450,” Motocross Action (December, 1974), pp. 38-43.

[3] Interview with Wilhelm Maisch Jr. by David Russell, (date not recorded), 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg). Maisch’s characterization of Wheat as brilliant is a direct quote.

[4] AMA News, “Sportsmen Competition, Points Standings” AMA News (September, 1970).

[5] Interview with Gunnar Lindstrom by David Russell, January 7, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[6] Cycle Guide, “They’re getting bigger and bigger—and bigger” Cycle Guide (February, 1970), pp. 47-8.

[7] Interviews with Dennie Moore by David Russell, March 27, 2007 through November 14, 2013, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[8] Sieman, “Maico’s Earthquake Machine.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] TT/scrambles. American “TT” racing (short for “Tourist Trophy”) and scrambles racing were often predicated on a ½ mile dirt track, with several additional features such as a low jump and turns added, as required by the rules. Scrambles racing evolved into the somewhat similar sport of motocross in America, in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

[11] Rick Sieman, “In Defense of the 501,” Old Bike Journal (February, 1997).

[12] Phone conversation between Dennie Moore and the author, November 14, 2013

[13] Modern Cycle, “The Maico K-501,” Modern Cycle (September, 1971), pp. 17-21.

[14] Sieman, “In Defense of the 501.”

[15]German Maico likely did not alter the performance of the 501 from its introduction in 1971 through later editions, due to the factory’s limited interest in the model. Furthermore, horsepower figures often vary from dynometer to dynometer. Lastly, figures may be taken at either the countershaft (direct engine output) or the rear wheel (power loss due to system friction), which will result in different figures for the same engine.

In 1968 I was riding for Cooper motors and “Uncle Frank” as I called him. I rode the 360 model for Maico , CZ 250 and 125 DKW/sachs in motocross . Two motos each class, so 6 races in a day. In August of 1969 I was drafted, but at Ascot park, a week before I went in, I was asked to race the “prototype” 501 three speed Maico against Gary Bailey, John Desoto and numerous others at the only motocross at Ascot that I know of. It was a handful but I finished second to Gary. Lots of great memories. Brian Faber was important to the development of head angle and the enclosed air box.

Lon–fascinating hearing that! Great to hear of some proof of the original 3-speed 501. (Funny, my old friend–and Eastern Maico distributor–Dennie Moore once said words to the effect of “Heck–it could have been a single speed in that bike!”) Not many stories of guys racing 501s in motocross–it must have been a handful!

Dave

I also lived in La Crescenta as a teenager and went to CVHS, just like you. We had met a few times as you were one year ahead of me. We raced at Deadman’s Point a couple of times before your were drafted. I knew your dad really well (even dated Tina a couple of times) and I traded my 1968 Penton 125 Six Days for your ’68 CZ250 twin pipe. This was while you were in Viet Nam. He would tell of you racing the 501 at Fontana Raceway. After that I bought your ’69 Maico X4A square barrel that was sold to another friend. I saw you race your DKW 125 at the Viewfinders GP (1970?) at Indian Dunes after your served your duty in the Marines. Was told you were combat wounded. You placed just behind Gene Cannady. I was shocked to hear about Von in Baja in 1975. I met him a few times also. I am still riding in 2023 at 73 years young. Would like to re-connect. God bless.

AMA Pro Flattracker John Hately rode one at an Ascot TT leading Dave Aldana on a Kawi 350. I fell while in third on my Champion Yamaha 360. This was back in ’73. That 501 was explosive out of the corners.

Interesting Tom! Yes, the 501 was not made for the weak!

Really liked your article on the Maico 501. I have a 74.5 GP framed 501 and love the bike. Also, I noticed my friend Henry Gref on your website….what a great guy he is! Thanks again for the article on the 501, I can’t wait to read part 2.

Thanks, John! We’ll have part 2 on, soon. BTW, we haven’t heard from Henry in a while–didn’t see him at VMD again. Hope he’s well! If you’d like, would love to see a photo of your 501–not many of the 74.5s around (send to vintagemotortees@gmail.com). v/r, Dave

THE ABBREVIATED STORY YOU ARE ABOUT TO READ NEVER HAPPENED IN 1972:

I came across your article through nostalgic reflection, as a friend kept a 501 in my father’s cabinet shop. His father disapproved of his owning one. ……… Anyway, as a storage fee, I was permitted to ride the 501 on open land near our home………The 501 was so powerful, it only felt safe on moderate terrain and easily created its own “track” by repetitive laps of any configuration and design. ….. One day , after plumes of dust blanketed some nearby homes, police converged on me and a friend (on a CZ 400) for being a public nuisance. The 501 was a rocket compared to police pursuit vehicles, with 50 ft roosts, instant acceleration to top speed, and effortless wheelies. The raw superiority of the 501 made breaking the law against off-roading a joy. No police car teams were ever able to corral me on the 501! The same performance principle held for the CZ 400! ….. Where is this kind of freedom and fun available today?

Joe Van

Hey, Joe–I think all of us might have a story hidden away about running from the police on our dirt bikes! (Don’t tell the kids!) Dave

After 50 years of searching I found my 1972 Narrow Frame 501 in yellow. The first thing you notice about the bike is the massive head and square fins. The head looks like a proto type high rise condominium. The other components of the bike share many of the parts common to 400 and 250.of the same year. I could sit for hours a look at the 501 because there is no bad angle. Superbly well executed bike of its era. Ake , Adolph and Willie were piloting superb machinery in the 70s.

Keith,

I like the view, sitting on a 501, and being able to look down past the tank, and see head/cylinder fins on both sides! haha!

I had a 501 in the early 70’s. I’m pretty sure it was a ‘60 model . It had 4 gears and YES it only needed 2nd and third. And YES I had friends clock me in a car at 100 mph on the street. I lived right in the middle of the D/FW area and just rode MX sportsman classes – usually had to ride intermediate class as there was no open class beginner level at any of our local tracks. I was all of 140 lbs and 18 years old and took an ass whoopin every time I got on that thing. It had no problem dragging me kickin and screamin into 1st place in the first turn – but I was never able to stay in control of that monster for an entire moto. BUT – I really had fun on it. Should have never let it get away. Think I paid $500 for it and traded it away for a 68 BSA chopper…. We all did stupid shit at 18 !

Seems early to have been a 501, Brad, but–given that it was a Maico and sometimes there’s no pinning them down–who knows? Yes, we all did a few things I wish we could take back. (At least we survived!)

That would be a ‘69 model.

Thanks!

Don’t kick yourself, Brad. I remember a 501 in the local paper, circa 1978, for $100…and I JUST DIDN”T HAVE ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS! AAAAHHHH!!!!

By the way, Bill Fischer sent me picks of his GRAND-DAUGHTER on her first solo motorcycle ride. She’s on his 501! I guess a)Bill’s a good teacher; b)his grand-daughter is a careful rider; and c)the 501 is a fairly tractable, predictable bike to ride! Dave