No products in the cart.

In the past we’ve looked at several motorcycle collections on the east coast (including, most recently the collection of “Yankee Bob” Fornwalt), enjoying a walk through both the artifacts particular enthusiasts have chosen, as well as the manner in which they’ve elected to display them. Most of us seem to have assumed that The Garage is where we’ll keep our bikes. That makes sense for many reasons. And, sure—if we really press the limits of familial love–maybe we can manage to sneak one or two (or more) bikes inside. (Note: a motorcycle inside the house should no longer be considered just a motorcycle; it is now an “Art Object”. Remember this for the future defense of your decision.)

Nonetheless, as we move through the years, perhaps growing tired of tripping over the same motorcycles, sprawled in the dark recesses of our garages and basements, someone will eventually say the words, “You should have a museum!” Right, we think—a museum! And, maybe Bill and Joe could bring their bikes! Let’s see . . . we could buy an old bank or church . . . spend $100K restoring it . . . and then we’ll advertise! Then, reality kicks back when we envision the potential lack of interstate travelers willing to divert to a Dirt Bike Museum, and the resultant two-paying-customers-per-week, and wonder who exactly is going to be staffing our Museum . . . and, we abandon that idea, again! Ah . . . but what a dream it would be, wouldn’t it! (Oh, and don’t feel too bad: Operating a museum is not an easy lift, and no museum funds itself solely through gate receipts—not the old Museum of Vintage Trail Bikes, not the National Motorcycle Museum, not The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ALL museums, today, need additional funding, above simply people paying at the door.)

Still, there do exist motorcycle collections displayed for viewing, privately and publicly. The financial models vary; some are maintained by the owner, alone, and others depend on other means—like being “event locations” for weddings and conferences, or via special fundraising activities (like the AACA Museum’s “Autos & Ales” night). But, in all cases, someone is putting a lot of money, or extra work—or likely both—into keeping the doors of a museum open!

South Central Pennsylvania’s Scott Fetterolf no doubt had the same dreams we’ve all had; he, however, acted on them. Scott is a long-time bike enthusiast and competitor (both road-racing and MX), began the Toy Tech Toyota repair partnership in 1991, and has operated Toy Tech Husqvarna since 1999 (Go ahead and say it, Scott: “The biggest motorcycle dealership in Grantville, PA!”) And, like all of us, Scott didn’t get rid of all his old motorcycles, nor did he resist buying others. And, also like us, he wished he had a place to store them—or event display them. So, when Scott and Vicki bought their home in the country, they planned a garage that could not only store stuff, but also display stuff—that is, be a museum, even if not a huge one. Thus, adjoining Scott’s large heated pole barn is a very special, paneled room: “The Museum” (as we all refer to it). It is, his friends would say, a beautifully unique example of how to display a small motorcycle collection; perhaps the best that any of us have encountered. Basically, it is the dream of most old bike guys. Let’s take a walk through The Museum.

The “museum” room in Scott’s outbuilding is completely finished, heated, and set up for viewing and relaxation. Themed benches and chairs allow visitors to sit and talk, while a flat table holds books and magazines (and fine dark beer, should the situation demand it). Yes, it’s busy (lots of stuff), but the contents are carefully and neatly organized. (One thing that can degrade a great collection—of anything—is too much, or disorganized stuff. There are reasons museum employ “curators” to decide what & how their stuff is displayed—and traditionally only display about 1/3 of their holdings. It’s very easy to get to the “too much” stage.)

Scott’s display collection (as opposed to the more common All the bikes and stuff I own!) share quality and context. First, no motorcycle makes it into the museum wing until it is of exceptional quality of presentation. There are no “Oh, yeah, I’m missing the engine to that one . . .” display bikes. Each machine is at a similar level of restoration or preservation—no rust, no incongruous or extreme parts or modifications. Also, the bikes (for the most part, excepting Scott’s old Ducati road-racer and a 2004 Husqvarna SMR630 Eddy Seel Replica (imagine finding replacement 16.5 inch tires for that one) are all off-road examples from the late 1960s through the 1980s. Here, no one brand governs the collection (though Scott is clearly attached to Husqvarna); the best examples from various iconic manufacturers share the floor. Above, a 1973 Honda CR250M Elsinore (left) shares space with a rare 1977 OSSA Phantom 250 GPIII—the dawn of the future of dirt bikes (Honda), and the last efforts of an old European stalwart. Note also the neat and careful display of the many posters and paintings. Note also that the overall display is brought together and made more cohesive by using matching bike stands, complementary & same-size carpet pieces, etc.

Creating a bit of visual drama and also saving some floor space, the mounting of bikes on the ramps works. Scott interplays contemporary artifacts with the motorcycles (Maico folding chair and gear bag; Castrol sign, etc.) to create visual interest and allow the items to help explain one another. On the left, a 1977 Maico AW400 appears ready to launch, as a 1978 Montesa 360 VB—another rare Spaniard—eyes a line to edge ahead on. On the right a 1977 Bultaco 250 Pursang likewise “sets its controls for the heart of the sun.”

OK . . . Hondas, OSSAs, Maicos, Bultacos, Montesas . . . But is there anything really unique or rare? How about this 1977 SWM RS 250MC (motocross)? Scott searched years for an SWM. (I don’t think I can recall anyone who has an SWM in their collection! Scott notes that the front number plate is indeed odd, but OEM. Ohlins piggyback shocks and only 208 pounds, dry—surprisingly light for a long-travel production bike!

Speaking of rare and unusual bikes, how about a 1983 Cagiva 125MX? Scott restored the bike with all OEM parts. The carburetor is an unusual magnesium body unit.

A beautiful 1975 Heikki Mikkola Replica CR250GP Husqvarna. This machine was slightly upgraded for vintage racing (billet triple-clamps, Mikuni, Excel rims, etc.), but the consistent level of finish allows it to fit in with the other display bikes.

This 1974 YZ250 is a new, unused example that Scott purchased from the Yamaha dealership (Jack Nye Cycle Sales in Millersburg, PA) that he worked for in high school. When Jack Nye’s closed its doors in 1983, the 1974 YZ that Scott had adored for years—and Jack knew would be a collectible—still sat in the corner of the showroom. In 1983 Scott didn’t have extra money for old motorcycles, and, anyway, assumed the bike had been sold at auction. Nearly 20 years later in 2001, Scott was working in his dealership when he received a call from Jack, asking whether he would be interested in purchasing the YZ—Nye had never sold either the building nor the bike, and it was still sitting in the same corner! Scott gathered up some money and headed to Millersburg the next day (the trip normally takes 40 minutes; Scott estimates he “made it in 20”).

Collecting the never-started motorcycle, the only obvious faults were a missing clutch cable (Jack had removed it for a customer, years before, and hadn’t ordered a new one) and a right side throttle grip, cracked and falling apart from age. The cable turned out to be the easy replacement; the grip, not as easy! Five years later a new-in-the-wrapper pair appeared on eBay, and, after spending $256—apparently somebody else also needed a grip or two!—the YZ had its missing throttle grip. Ultimately, this is attention to detail that is not universal, and deserves applauding; it demonstrates that if it’s in this collection, it’s correct.

Goodling’s Motorcycle Sales in Millersburg, PA (circa 1959), before Jack Ney bought the business and moved it (literally) next door, onto his own property. Jack had worked for the Goodling family, and continued business as “Goodling’s Motorcycle Sales—Jack Ney, Proprietor.

Scott purchased this NOS Pennzoil sign at the Hershey Auto Show and had the old Goodling’s/Jack Ney sign from the 1970s and 1980s re-created on it. (I LOVE this idea! Can you think of a dealer from your past—maybe the one you swept floors at, or the one you bought your first motorcycle from—whose re-created sign you’d love to see gracing your garage or collection? FastSigns and like businesses can do wonders; think about it!)

Included in the collection are glimpses of Scott’s many other interests: boots, helmets, oil cans, gas tanks, mouth guards . . . even handlebar grips (have you considered not just the various styles and colors, but the evolution of such a simple item?). Despite there being a lot of these items to see, the Fetterolfs know when enough is enough. (A common error with private, non-curated collections is to simply put everything you have on display—to cram one more of these on every remaining bit of floor, wall, or shelf space. At a point, however, the mass of items enters ‘information overload’ and each additional authentic-but-stained tee-shirt or poster on display only detracts from the viewing experience. I’d humbly suggest that the Eastern Museum of Motor Racing in Dillsburg suffers from this tendency.) In his business, Scott deals in all the contemporary forms of motorcycle accessories, and his helmet business is a major aspect of that. Even though 35-50 years newer than the oldest dirt bikes in the collection, these modern Troy Lee helmet designs work perfectly with the exhibit. In the row of vintage boots, note the brown leather pair; these were marketed by CZ, and bear the great manufacturer’s logo.

“Husqvarna row” in the main garage area. Being a Husky dealer and enthusiast, Scott naturally has quite a few extra Huskys sitting about. (Wouldn’t it be nice to just . . .you know . . . pull a new bike off the line, occasionally, and tuck it away?)

Motorcycles in the center row include: 1971 DKW MC125 Boondocker; 1974 Hodaka Super Combat 125, 1977 Honda CR125 Elsinore, 1978 Suzuki RM250C, 1982 Sachs/Nauder 125MX (how’s this for unique?!), 1983 Husky CR250, and a 1982.5 Husky CR500 Silverstreak (500cc). On the very end is the Eddy Seel Replica.

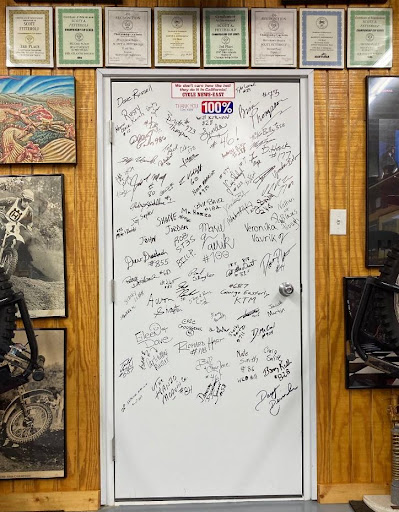

The door to the Museum doubles as a sign-in registry for past visitors. National figures such as Gunnar Lindstrom and Ed Youngblood have signed, as well as very-well-known local and national racers like Brian Thompson, Seth Hammaker, and Damien Plotts. Can you recognize some blasts from the past?

Adjoining the Museum is the rest of Scott’s garage—also a space many of us would also love to have. Here is storage, work area, more storage, and more motorcycles. Why the small Japanese and Italian street bikes? Well—because they’re just beautiful! “Conditionally collectible” is a term I’ve heard, essentially meaning that if the motorcycle is nice enough, someone will want it and want to see it. And these pristine little motorcycles certainly meet that bar. Again, note the clean, organized, not-overly-busy display of artifacts. This area is also used for entertaining.

Ultimately, the Fefferolf collection must be appreciated for not being a scattershot collection of everything. It is rather a focused insight into mid-to-late-seventies off-road technology, when the “long-travel suspension revolution” had taken root and resulted in truly high-performing, “modern” motorcycles. Scott seasons the display collection with pivotal early machines (such as the 1973 CR250 Elsinore) and follow-on water-cooled, disc-brake examples to thoroughly explain the evolution of the dirt bike. Thank-you, Scott and Vicki for the tour! More “great collections” are on the way.