No products in the cart.

Motorcycle Culture, motorcycle oral history

Definitions, and the Maico as Material Culture 1.1

A Social History of Motorcycle Technology

This post and many to follow is a social history of a technology. By this I mean that it examines an item of technology—in this case the German-made Maico motorcycle—and explores the links between the object and that segment of humankind who interacted with it. These people and groups both affected this motorcycle, and were affected by it. As historian Carroll Pursell stated, this approach to history emphasizes the “social role of technology—the way in which it interacts with other aspects of American life . . .”[1] We will see that the product of a small German company became tightly entwined with a passionate group of competitive American motorcycle riders, and that this piece of technology can be interpreted as material culture, in order to provide us insights into the lives and values of this group. Other sources of information will assist in this investigation—oral histories, literature, and photographs, to name a few—but the technological device uniting the group will serve as my central point of inquiry. Through the careful examination of these sources we will see that the members of this American group shared values and communal behaviors, differed significantly from other motorcyclists, and, while resisting some societal influences, were still products of the rapidly changing times in which they lived.

Defining motorcycle riding: activity or sport?

A key difference between the men and women addressed in this text and motorcycle riders as a whole concerns their use of the motorcycle. Motorcycles are rightfully considered a transportation device—they certainly move a person, physically, from one place to another—but this larger description naturally divides into smaller subsets, differentiated by the machine’s use and the groups’ feelings about the role of the motorcycle within their culture. In the United States we routinely observe several such differing motorcycle groups. Prevalent on American roads are the “bikers”—the black-leather-clad, somewhat conformist, sometimes posturing group, emanating a certain rebellious attitude. There are also basic commuters, riding practical motorcycles as an efficient or enjoyable means of going from one place to another. In past years there have appeared the “crotch-rocket” or “rocket-bike” riders—the most recent incarnation of young men on fast motorcycles, laying low, road-racer style, with feet far back on loud motorcycles which are sometimes every bit as fast as the 200mph road-race machines they are modelled upon. Aside from these principal groups, there are many smaller subgroups, united by identity, brand or type of motorcycle, and preferred riding. Americans encounter Cruisers, “Dykes on bikes,” chopper riders, BMW riders, vintage Japanese (or British or Spanish) riders, “rat” riders, veterans’ clubs, “one-per-centers”—but all these can be discussed another time. The final principal group of motorcyclists, I argue, are not highly visible on our public roads at all. If they are seen, it is in the context of hauling or towing their motorcycles to the racetracks, off-road vehicle recreational areas, or other places where they can legally ride. This group is what I call the motorcycle sport rider. By motorcycle sport rider I am describing both those motorcycle riders who engage in a variety of organized motorcycle competitions, and also those who recreationally use motorcycles in off-road environments. While these riders are using their motorcycles as transportation in the most literal sense, they are much more concerned with enlisting the motorcycle as a tool in some manner of competition or struggle against time, terrain, other physical obstacles, each other, or a combination of these things. Racing motorcyclists ride in organized competitions, including road-racing on paved tracks and a variety of events on unpaved terrain, to include motocross, enduro, cross-country, and trials. While recreational off-road riders may not be engaged in actual organized competition, they are, like their organized racing contemporaries, engaged in an individual physical struggle, pitting themselves, their motorcycles, and their individual riding abilities against natural obstacles. These obstacles may be hills, streams, mud, vegetation, the desert, rocks, or other natural barriers to man and machine. In this light, we can view the lone off-road rider in the same way as we might view the mountain climber, sky diver, or individual long distance swimmer—and, of course, the racing motorcyclist. Sport is their interest—not transportation, sightseeing, cost savings, or posturing—and these riders are sport riders.

Locating the differences between these sport riders and other transportation-centered riders is critical to the identification of the former group’s unique motives and values, and, I argue, their culture. The division between sport and non-sport riders can be an blurred one, and moving beyond the obvious fact that both groups are on motorcycles is a more nuanced distinction that many observers may not bother to make. To objectify the comparison, we should consider American society’s understanding of what constitutes ‘sport.’ Dictionary definitions of sport include “an active pastime: recreation;” and, a “specific diversion, usually involving physical exercise and having a set form and body or rules.”[2] From this definition, how do we categorize the American tradition of cheerleading, for example—is it a sport, a game, or just an activity? In the case of cheerleading, though a very physical act, school districts in the United States have usually termed it as an activity, due primarily to the lack of competition.[3] Card playing and chess, on the other hand, involve competition, but lack the physicality expected of a sport; thus we consider these pursuits to be games—albeit a highly challenging and intellectual one in the case of the latter. I use similar criteria when considering on-road motorcycle riding to be an activity; it is essentially transportation: getting the rider from one place to another, be it quickly, cheaply, stylishly, or enjoyably. We should see that the two forms of motorcycle riding differ fundamentally. I take special care to note that this theory is not meant to ignore or demean the rigors of street riding. Environmental conditions, traffic, and the physics of controlling a statically unstable motorcycle do require preparation and skill on the part of riders. Furthermore, a recent category of street motorcycle and rider also complicates the issue; this is the ‘sport bike’—a term used by manufacturers to describe the informally-named ‘crotch rocket’ pseudo-road-racer previously referred to. This is a street-legal, high-performance motorcycle possessing capabilities that seasoned road-racers would have difficulty harnessing on a race track—much less the highway, as expert road-racers have attested.[4] Riding this type of motorcycle—or any motorcycle—to greater speeds and experiencing the limits of cornering capabilities, legally or illegally, certainly involves the risks and physicality of other individual sports. I leave study and further classification of this type or riding to others.

Motorcycle Cultural Definitions

Since I assert that the sport riders are a subculture of the greater motorcycling culture, it is important to establish precisely what these terms denote. First, I refer to a commonly accepted definition of culture, that being “the totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions and other products of human work and thought typical of a population or community at a given time.”[5] Referring to the greater American “motorcycling culture,” one can readily observe these aforementioned traits—at least as they are applied to the more visible on-road segment. This group, for example, practices “the wave” to other riders as they pass on the road[6], dresses similarly, adorns its motorcycles with certain standardized symbols (such as American POW flags, if the motorcycle is a Harley-Davidson), admires excellence in the art of custom paintwork, shares the common relative danger of riding on the road, and communicates using a common lexicon of motorcycle-relevant words.

My use of the term subculture is again literal and refers simply to a “cultural subgroup differentiated by status, ethnic background, residence, religion or other factors that functionally unify the group and act collectively on each member.”[7] The primary difference between sport riders and non-sport riders, I have said, is the purpose for which they use the motorcycle. They also differ in other, secondary ways which further differentiate the two groups from one another. (Categorizing the motorcycle rider in a single group—or single type of rider—is fairly uncomplicated. While many motorcyclists engage in more than one riding activity—for example, off-road riders may also ride on the road, and a Vietnam Veterans of America rider may also be a Harley-Davidson owner—they tend to self-identify themselves with one principal group. Also, the skill sets for various types of motorcycle riding are not necessarily transferable: arguably, an off-road rider/racer can adequately handle a street bike, but a strictly on-road rider’s abilities may not translate well to purely off-road conditions. This specialization of riding skills tends to affirm the ‘one group’ mentality among riders.) I will describe the values, mores, and practices of the sport community specifically, and in much greater detail, in the course of this work.

The Maico as Material Culture and Artifact

The central material object uniting the culture being studied here is the Maico motorcycle. Using material culture techniques, this man-made object will be evaluated in order to extract significance and meaning. The Maico motorcycle may also be referred to as an artifact, since it is thing “created by humans, for a practical purpose.”[8] Some scholars would further classify the motorcycle as a tool—a man-made object intended to accomplish work.

Utilizing material culture methodology to examine the Maico motorcycle not only reveals the most information about the object, but also stands the best chance of informing us about the people who built it and used it. E. McClung Fleming writes that, “To know man, we must study the things he has made.”[9] Fleming notes that, historically, the study of man’s artifacts—his material culture—has actually received less attention than the study of humankind’s other two major forms of culture—social and mental (or ideological).[10] This is not surprising, as a written record is generally more accessible and easily studied than the artifact: a clean book in a climate-controlled library, versus material culture, lying broken, dirty, silent, and undiscovered. Yet material culture examination holds some advantages over the study of the other two areas, and in some situations is the only way to study a culture. For example, most pre-historical history is necessarily conjectured completely on the basis of material culture, these times by definition lacking written records. Archaeologists and historians reconstruct ancient worlds, as best they can, through the analysis of the found items which may constitute the only record of these societies. Fortunately, I have at my disposal not only material culture, but an array of written and visual records with which to portray my subject. This study will be a holistic examination of written records, oral histories, and photographs—as well as the motorcycle.

Regarding written records, historians posit that our age-old fixation on writing as our primary historical portal has actually inhibited our learning—or at least weighted it towards the circumstances and culture of the writers. First, writing is a relatively recent development across the arc of human history, and—in the well-informed convenience of hindsight—we now understand that writing has always been more a device of the educated and elite, rather than of common and working folk. Thus, formulating ideas primarily based on the study of written records is to possibly take for granted the viewpoints of a narrow class of people who possessed the ability—or inclination—to write about their experiences, and to accept their (written) word for it. For example, can historians on the middle-ages expect the aristocracy to have accurately conveyed—or even understood—the mindset of the serf? Can we truly learn about an American slave’s point of view from the diary of her master, or of the values of the common sailor from the Lord of the Admiralty’s campaign memoirs? We see that it does not necessarily follow that with the presence of writing in a culture, that that expression should become the preeminent mirror of that society, while material objects become relegated to secondary historical value. On the contrary, the way we create, use, and relate to objects offers substantial information for the scholar of any period who is equipped to decipher it—and may, when compared to contemporary written records, be the more revealing source of information. Motorcycle racing, a pursuit largely of the working class,[11] falls into exactly such a category, wherein comparatively little written history was produced by either the participants or observers. To gain the fullest understanding of motorcycle competition in American, I apply all means at my disposal; the holistic approach will best be able to complete or correct the record where the written word fails. Similar to the approach of modern historical archaeologists such as James Deetz, this work takes a comprehensive stance in its study of both the artifact and every other source of information—written, oral, and visual—that is available.[12]

Scholarship, History and Cultural Relevance

Even within the field of material culture studies, some objects have sometimes held inordinate importance. Scholars have long had a preoccupation with—though explicably—the artifacts of the elite and wealthy. Whether due to the quantity of surviving elite objects (consider the odds for survival of a 1700s wooden plate versus that of a silver teapot) or historians’ fascination with these finer things, scholarship has at times been centered on these existing objects and then assumed to be representative of all classes within a given culture. Folklorist Warren E. Roberts notes his experience of reading in history books of “the typical hostess in Colonial America” setting her table, and then seeing a list of high-end table furnishings that no “farm wife”—then comprising over 90% of the American population—could have dreamed of really owning.[13] We can see how these historical writers made their understandable mistake; after all, for every surviving wooden table setting, there may be twenty or thirty surviving period pewter or porcelain settings. Why? Besides being impervious to the deterioration which would have plagued wood, pewter and porcelain objects are generally considered far more valuable. Off-road and competition motorcycles similarly fall into this dilemma, due to their more disposable nature. Dirt bikes (as we refer to off-road machines), especially, were ridden hard, often neglected, became technologically obsolete within several years, and tended to suffer the same fate as old lawnmowers: discarded and left to rust. Not only were these machines used up in the course of their service lives, they also tended to be owned by young and less-affluent off-road competitors, who may not have had the means to store the bikes indefinitely. Street motorcycles, on the other hand, usually have an easier life. The external appearance of the generally more expensive street bike is habitually better-maintained, they are not ridden in the same harsh conditions, they are usually stored inside, and they stand a much better chance of having been owned by older and possibly more elite riders. There are exceptions; Steve McQueen’s Husqvarna dirt bike may be more valuable than most other motorcycles on the planet, and some off-road riders did indeed save and preserve their machines. However, this is not the norm.

Methodology

Material culture scholars have created various working methods to standardize their approaches and maximize their opportunities for results. Folklorist Simon Bronner teaches a four-part methodology incorporating: Introduction/review of questions; Findings (description and history of the object); Interpretation and conclusions; and Amplifying data (photographs and charts).[14] E. McClung Fleming proposes a similar four-part method, consisting of Identification (object description), Evaluation (judgments about the object), Cultural analysis (relationship of the object to its culture), and Interpretation (significance).[15] Jules David Prown describes his three-part art history/archaeological-derived approach as Description (analysis and content), Deduction (engagement and response), and Speculation (theories and hypothesis and a further plan to investigate questions posed).[16] Finally, the work of Thomas J. Schlereth and (once again) James Deetz reminds us that every source of information relating to an object/artifact is a source worth considering and thoroughly exploring, from wills to old photographs, grave markers to mail-order catalogs, the written and oral statements of observers, and the clothing they wore.[17] Everything can inform us, if we allow it to. My work incorporates the methods above—with particular deference to Fleming’s model—and keeps Schlereth’s and Deetz’s guidance strongly in mind.

Directing my inquiry towards the culture’s principal artifact—the Maico motorcycle—I ask the following questions:

*What are the origins and composition (physical and design) of the motorcycle?

*Why does it look as it does?

*How does it do what it does?

*Who used it? Who made it?

*How did the object affect—and what did it mean to—its immediate users

and those with which it made contact?

And, ultimately,

- What can we then deduce about the object’s makers and users, and the society which existed around this object?

After careful and sequential deconstruction of the motorcycle, I argue the following specific points:

- That the very individual aesthetics of the Maico—its squared, severe lines, sculpted form, and rough finish—are the result of performance, cultural, and economic pressures from Germany and the United States.

- That the overall functionality, reputation, and modification possibilities of the Maico motorcycle made it a favorite of the most dedicated American racers.

- That the company’s American distribution systems were a major cause for the company’s success, and corporate changes made to this system over time negatively affected the distributers, the dealers, the riders, and ultimately the Maico company.

- That off-road and competitive (sport) motorcycle riders in the United States—to which Maico motorcycles appealed— constitute a definitive subculture within the overall motorcycling culture, with specific group values, behaviors, and mores.

- That Maico’s technical advances were significant in its time, and continue to influence motorcycle design to the present day.

- That the dynamic off-road motorcycle culture in the United States in the 1970s was related to changes in American society, but at the same time retained a conservative tendency.

- That Maico’s failure in 1983—two years after producing one of the finest competition motorcycles ever made—resulted from a combination of management errors, family infighting, and world-wide economic conditions.

Use of oral histories and visual references

Oral histories from first-person-observer sources figure predominantly in this work. Protocols from the Penn State University Institutional Review Board (IRB), governing the proper collection and use of this research, were followed. The narratives were recorded prior to and during the writing of this work from phone conversations and some person-to-person live interviews, and the speakers were informed that their statements would be used later. Each oral history has been repeatedly provided to the speaker for approval and corrections, until both the speaker and I were satisfied with the result. Copies of the complete oral histories are on file in the Humanities Department at Penn State University, Harrisburg, under the title Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, in the Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies.

The oral history is currently very much embraced by historians, and provides a directness, flavor, honesty, and paths to other sources—if not always absolute accuracy—that offers immense value for social science research. In the case of this dissertation, I was very much influenced by the oral history work of Studs Terkel and Al Santoli.[18] I encourage readers interested in the subject of early American sport motorcycling to access the original oral history transcriptions of my interviews with the speakers, for the speakers’ full narratives.[19]

Period advertisements were used to a great extent in this work. Much of the Maico company’s advertising—which, in the United States, was mostly funded and created by the American distributors—was print advertising and is very accessible in the pages of period enthusiast magazines. These advertisements were then digitally scanned. Examples of advertising handouts and extracts of technical manuals, produced by German Maico for use by distributors, dealers, and owners, have also been scanned and referred to extensively.

Finally, this dissertation would not be possible without access to the personal photograph collections of many enthusiasts. These amateur snapshots not only convey factual information about the Maico motorcycle and its riders, but also allow us to read the images for clues to the overall styles, values, and cultural markers of this past generation. As historian Alan Trachtenberg points out, American snapshots are often “constructions,” showing us not simply what was, but what the characters in the images and those depressing the camera shutter wished us to believe.[20] With this material asset, added to period literature, oral histories, and the motorcycle itself, a comprehensive image of American sport motorcycling emerges.

[1] Carroll Pursell, The Machine in America: A Social History of Technology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), xi.

[2] Webster’s II New Riverside University Dictionary, Boston, MA: The Riverside Publishing Company, 1984.

[3] “Competitive cheerleading,” pitting one squad against others in the execution of acrobatics and other criteria, is conversely recognized as a sport due to the presence of competition.

[4] Interview with Craig Shambaugh by David Russell, September 11, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[5] Webster’s II New Riverside University Dictionary, Boston, MA: The Riverside Publishing Company, 1984.

[6] “The wave” is the practice of waving of a free hand at a passing motorcyclist and receiving one in turn, presumably signifying solidarity between riders.

[7] Webster’s II New Riverside University Dictionary, Boston, MA: The Riverside Publishing Company, 1984.

[8] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., s.v. “artifact.”

[9] E. McClung Fleming, “Artifact Study: A Proposed Model,” (Winterthur Portfolio 9, 1974, ed. by Ian M.G. Quimby), 153-173.

[10] The three aspects of human culture are variously referred to as material, social, and mental (E. McClung Fleming, quoting Leslie A. White’s The Science of Culture, 1969, 364-365) or ideological (Thomas J. Schlereth in “Material Culture Research and Historical Explanation,” in The Public Historian, Fall, 1985).

[11] “Working class” (also, “blue-collar”), for purposes of this dissertation, these terms are roughly defined as relating to “the class of wage earners whose duties call for the wearing of work clothes.” “Middle-class” is used to suggest “a class occupying a position between the upper class and the lower class,” and, “a socioeconomic group composed principally of business and professional people, bureaucrats, and some farmers and skilled workers.” Both definitions are taken from Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 2003.

[12] James Deetz’s multi-disciplinary method of material culture examination is beautifully evident in In Small Things Forgotten (1977), The Times of their Lives (2000), and Flowerdew Hundred (1993), among other works.

[13] Warren E. Roberts, Viewpoints on Folklife: Looking at the Overlooked (Ann Arbor, MI:UMI Research Press, 1988), 6.

[14] As taught to the author while he was Dr. Bronner’s student at Penn State Harrisburg, 2005-2006.

[15] McClung, “Artifact Study: A Proposed Model,” 9.

[16] Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” 1-19.

[17] Thomas J. Schlereth, Artifacts and the American Past (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1980).

[18] See Studs Terkel’s The Good War: An Oral History of World War II (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984) and Al Santoli’s Everything We Had (New York: Random House, 1981).

[19] Copies of the original oral histories are available at the Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg, under the title Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection.

[20] Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, xvi.

It’s amazing that there are numerous categories in terms of bikers’ types. I like the term ‘one percenters’.

It’s interesting to see what the purpose a biker has. Whether the biker views the bike as a medium of sport or something else like hobby.

I guess it’s like other sports where there is a similarity. For example, in soccer, there’s street soccer which is getting more popular. I enjoyed reading it.

Hi, Tar. As you could see, I was most interested in how certain (sometimes mostly non-riding or late-coming) groups had essentially appropriated the identity of “biker” for themselves…leaving many riders out of the picture.

You meant the classification and distinction between riders and non-riders?

Yes that’s correct. Tar, you might be interested in reading anthropologist Barbara Joans’ “Bike Lust: Harley’s, Women and American Society”. She really goes into biker classifications

Hi there, your website is helpful for anyone passionate about motorcycles and I’m happy I have found it.

Your articles are well documented and the T-shirts proposed for sale are magnificent. Maybe if you can add some colors will be catchier but it’s possible I’m wrong. Anyway keep the good work you started here!

Cristina

Ha-ha. Yes, Cristina, we’re thinking about colors. I need my son, Chris, how sets all this up to steer me in the right direction! Dave

My first bike was a used 1959 Honda Dream 305. First thing I did was chop it. 13 degree rake and etenedxd tubes 9 . No front brakes and only rear drums. Scary as crap. Second was a basket case Harley, I think. It was a Pan head motor and the rest just went together. Rode that thing for years. Scary. Finally bought a 2001 Fatboy brand new from Anchorage HD and paid cash. Still have it. Some folks just have to learn from experience.

Motorcycles are such a rich part of our culture. It’s easy to think it’s all Hell’s Angels and what not, but it’s so much more as you’ve illustrated – especially motorcross in the 70s. I had a friend who made art out of discarded bike engine pieces and always loved it. Good stuff!

Thanks, James. It IS a wide-ranging culture. Insofar as your last comments (parts as art) you might enjoy the piece my son just posted (“The Motorcycle as Art”).

Your site is very well written and includes a tremendous amount of information. There was something that caught me, that you categorize the people who ride motorcycles. Every sport needs different values, as in everything. Dancers aren’t all ballerinas, each dancer chooses their own style. The thing they have in common is dance. As far as motorcycles are concerned they are all in the wind taking chances and making decisions. As you can guess I am a Harley fan, I feel that as we are involved in many charity events and rides for a cause it is also for our enjoyment also. The people I ride with waves to everyone on a motorcycle.

Nice site, I enjoyed reading about another style of riding. The t-shirts are quite unique.

TerryAnn

Hi, Terry Ann. I suppose my goal was to not so much push any group away from inclusion, but to note that sport/competitive riders–if anyone in the motorcycling community–should be honored as ‘real motorcyclists.’ I have nothing at all against Harley/’biker’ culture (I own a Harley, as do many off-road riders I ride with), but feel that this culture sometimes appears to insist that it is the only true, American motorcycle identity. It’s a “big tent,” as the expression goes, and we don’t want to exclude our brothers & sisters of any of the disparate value groups. Thanks again, and be safe out there!

as a cycler, i have found vainryg degrees of comraderie. mountain bike riders are almost always smiling and waving to fellow adventurers. road riders are much to fast to be bothered with such silliness. but here in Big D it throws everything out of whack. Even my own neighbors rarely return a friendly wave. Boo metropolis apathy

I think the issue can become that the “waive” becomes forced. You sometimes feel like you have to take your hands off the bars to waive at every rider on a pleasant day, and sometimes it seems more required than anything like heart-felt. Tough issue!

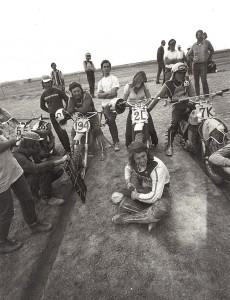

1970’s Vintage photo; probably 1981, #27 Mickey Kessler, #295 Kenny Adams, 103 Paul Schoenberg(?) all riding Maicos.

Thanks, Greg! Interestingly, Mickey Kessler and Kenny Adams were “local boys,” so to speak, coming from the eastern Pennsylvania area, I believe.

Thanks, Greg! Interestingly, Mickey Kessler and Kenny Adams were “local boys,” so to speak, coming from the eastern Pennsylvania area, I believe.