No products in the cart.

Maico, motorcycle resstoration

Change Is Good: Personalization, Modification and Performance Upgrades Part 3

The Vintage Motor Company is proud to release part 3 of 3 of our series on motorcycle personalization and modifications. New readers are encouraged to read part 1 of the series located here. Part 2 is located here.

Having discussed general aspects of motorcycle modification, we’ll regroup and return to the specific aspects of the classic Maico motorcycle.

Here, we’ll will encounter some of the challenges facing Maico riders, and the solutions and modifications with which American riders responded. Recognizing the original owners’ craftsmanship, ingenuity, and transmitted meaning will assist us in understanding the make-up, characteristics, and values of these men, as we progress through other chapters.

Owner modifications to Maico motorcycles; the chassis

The frame, suspension and wheels of a Maico were well-designed and executed, and—up until the advent of long travel suspension in 1973—usually were not in need of significant maintenance or changes. Breakages could be fixed by mechanically-inclined individual with proper welding equipment—an accurate characterization of the typical American motorcycle racer of the period. To be a racer meant to take responsibility for one’s bike; owning a Maico—a thoroughbred, single-purpose racing bike—implied this and more.

The frame itself was constructed of welded and brazed thin-wall chrome-moly steel. The frames are very strong, relatively light, and utilized geometry now considered classic. The swing-arm pivot assembly was brilliantly executed, consisting of a hard-rubber bushing carrying an inner steel tunnel through which the swing arm bolt would pass. Despite the fact that the rubber bushing required no lubrication—and the swing-arm bolt likely never received any—failed or even excessively worn assemblies are seldom noticed.

As we have seen, Maico frame geometry was excellent. Still, racers sometimes changed the steering-head angle to suit riding style or individual track conditions, by cutting and then adding or removing a short length (10mm or so) of tubing at the upper frame back-bone, thereby increasing or decreasing rake.[1] Ake Jonsson was known to modify all his racing bikes in this way, and also might cut and re-weld them back the other way, in the break between motos, if he felt track conditions warranted it.[2][3]

Long-travel suspension arrives

Almost as soon as the first forward-mounted, long-travel rear suspension (LTR) motorcycles were seen being campaigned successfully by the factory team in Europe, Maico pushed the technology downward to dealers and users. Factory racers and engineers were tasked with instructing distributors and dealers on how to properly accomplish the same modification on their pre-long-travel 1973-and-earlier frames (note in Figure 45 the new old-stock 1973 frame modified by Eastern Maico, to factory team specifications). Individual owners wasted no time in attempting to copy these modifications, whether crudely re-configuring the frame in the barn with an arc-welder, or by sending the frame to Wheelsmith Engineering in California or other shops for an expert job. This modification required shortening the existing air-box or fabricating a new one.[4] Owners’ answers to LTR modification ranged from the merely functional to beautiful, finely-executed metal and fiberglass work. LTR-modified pre-1974 frames can usually be differentiated from production LTR frames, primarily by the usually well-pronounced sharp bend in modified frames (as opposed to a more rounded rear sub-frame strut in the production versions).

In addition to the services offered by various companies to alter the stock steel swing-arm for LTR suspension, several providers offered entirely redesigned alloy swing-arms for all years, from the early LTR days, through to the end of Maico. These units were lighter and more rigid than the stock units, and were produced by Thor, Aaen, ProFab, and others. Chain-guide and chain-tensioner systems engineered into these arms also sought to mediate the chain-tension problems brought about by LTR. These swing-arms are beautifully designed and constructed, and are highly prized by vintage racers and collectors.

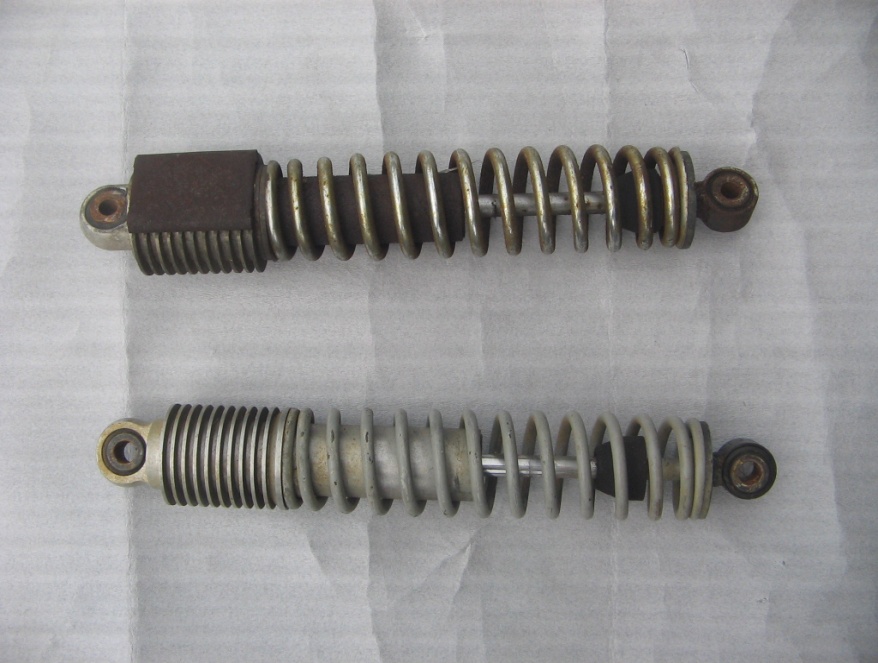

Rear shocks would fail, and were usually replaced periodically in the course of an off-road motorcycle’s career. Shocks might best be considered a consumable item, like grips and cables. Stock Girling, Koni, and Bilstein shocks (in the early-LTR era) tended to overheat and could be equipped with slip-on aluminum finned ‘coolers,’ a heat-sink machined by owners or purchased from suppliers. Soon the original steel shock body itself could be replaced—as in the case of steel Koni units—with the “Poppy” brand one-piece aluminum-finned body, early in the LTR era. In later months, Koni marketed its own aluminum-bodied shock. Of course, all manner of aftermarket shocks are found on well-used and un-restored motorcycles of the period. Factory racing Maicos were using hand-machined aluminum shock bodies even before the LTR era.

Maico forks–“the best a man could get”

Maico forks were long considered an industry standard and tended to be left alone. The 36 mm external-spring-type tubes—standard through the 1974 four-speed and 125cc 1975 models—were made 1 mm wider in overall diameter than the industry 35 mm norm at the time, and this tiny 1 mm significantly improved the strength of the fork tubes. The upper area between the triple clamps on these forks was always prone to rust, leading one to wonder if these tubes were ever plated at all. Wheelsmith offered an in-house extension to the lower aluminum slider and an accompanying damper-rod assembly modification, which increased travel by about an inch beyond the standard 7.5 inches, and was claimed to aid in cooling and to improve damping. Some owners considered the earlier one-piece fork springs superior to the later two-piece springs. Wheelsmith also sold one-piece replacement springs, claimed to be more resistant to sacking and with superior rebound characteristics. Aside from these and oil or spring changes, the only other modification one might attempt was to alter the profile of the two-piece aluminum block valve in the damper—as can be seen in the photos (Figure 47) of 1972-1973 era factory bike units. This modification provided a more constant oil transfer over time, and minimized hydraulic-lock upon extreme fork compression.

Fork damping fluids were sometimes a unique blend of ingredients, arrived at by the rider. ATF (automatic transmission fluid), actual fork oil, and other liquid lubricants (like Marvel Mystery Oil) were used straight, or mixed together. Riders took pride in novel fork fluid mixtures and passed on these recipes to others in the community; whether these blends actually worked better than standard fork oils is subjective. ATF, able to absorb dissolved water, may have helped to corrode ferrous fork internal parts. These “home brews” of fork oil helped to personalize the motorcycle, as they altered fork performance. The practice was not particular to Maico riders, but was a modification that a true enthusiast would make.

Details: foot pegs, air boxes, fenders, and handlebars

Early Maico foot pegs, both the initial non-folding design and the later folding, pre-1975 types, could be slippery and dangerous—particularly when wet. Since German weather can be even wetter than North American conditions, this was an odd design oversight. Some owners welded more pronounced “dimples” to the existing pegs, while others welded a serrated U-shaped cleat to the peg for additional friction. Wheelsmith offered its own solution to the problem, selling a beautifully-made, folding assembly utilizing a hardened bronze mount with a chromed, open, U-shaped serrated steel cleat. The Wheelsmith foot pegs were a beautifully-executed answer to a potentially dangerous failing, and were highly valued.

Air boxes, like the forks, were considered an industry standard. Other than those modifications necessitated by suspension changes, or additional sealing done for wet weather, no changes were usually made. Before the factory began fitting oiled-foam filter elements to new bikes, this upgrade from the stock paper filter was common. Aftermarket or homemade aluminum air boxes were sometimes constructed, replacing broken fiberglass units or as an opportunity to display additional aluminum work.

In the event that the motorcycle would be run in extremely wet conditions, the owner might go to great lengths to further keep water and mud out of the system. Duct-tape might be used to cover much of the top of the box, and silicone sealant was effective at closing small gaps around the air box and intake hose. Other wet-weather/mud precautions included silicone-sealing around the points cover and taping between the frame down-tubes, in front of the cylinder, to avoid mud build-up in the fins and over-heating. This process was not particularly attractive, but was functional.

Fenders on Maico off-road and “Scrambler” models prior to 1970 were of a rounded aluminum or steel (dependent upon year) style. Aluminum was acceptable—being light and able to be re-bent in the case of damage—but heavier steel items would have been a target for replacement by serious riders. From 1970 until the introduction of the new 1975 GP line, the beautiful, classic Maico fiberglass design was used. Extremely lightweight for its time and somewhat flexible, these fenders were also very prone to breakage. One magazine wrote that Maico fiberglass would “break if you look at it funny.”[5] When flexible plastic aftermarket fenders were released in the early 1970s by Preston Petty, Webco and others, these items became popular and practical replacement items. 1975 and later Maico original equipment designs were plastic by Falk of Germany, and were nearly indestructible. Period replacement fenders for the classic pre-1975 type were available in both flexible plastic and a thinner fiberglass.

Handlebars, hand controls, and grips on most European bikes were of excellent quality. Maico original equipment handlebars were a conventional chromed steel, cross-brace design on off-road models. Owners would have replaced bent bars with whatever brand and bend they preferred, probably opting for the least-expensive steel items. Occasionally solid aluminum bars were selected for dirt track use, but most riders considered these un-braced bars inadequate for the rigors of motocross. American Sport Racer—ASR, the subsidiary of Eastern Maico—marketed an “Ake Jonsson bend” steel bar, formed to the champion’s specifications (which can possibly be identified by a small white label affixed to the cross-bar). Handlebar grips originally fitted to Maicos, at least through the mid-1970s, were the thin, hard, black rubber Magura items. Being uncomfortable for some riders, in addition to being prone to normal wear, the Magura grips were commonly replaced with softer and patterned aftermarket grips. Throttles and levers were by Magura, top-quality pieces usually replaced only when they broke. The fitting of quicker-turning and straight-pull (ejecting the throttle cable parallel to the handlebars, not straight out) throttles was common.

Seats through 1972 were less-padded and lower than the 1973 and later items. During this time and prior to the implementation of the more heavily-padded seats, several United States companies sold “GP seat foam kits” to provide greater comfort on these earlier machines. Other than this, Maico seats were again considered among the most comfortable in the industry, and replacement with a different item or modification made little sense.

The Maico gas tank: iconic, but certainly not perfect

Gas tanks used on Maico motorcycles, original equipment and aftermarket, varied greatly. Prior to 1968, stock Maico tanks were made of steel and were of a nondescript rounded shape. Original equipment Maico gas tanks from 1968 through 1974 were the “coffin” fiberglass design and could be plagued by leakage. These tanks came in two sizes. They were commonly referred to as simply the “small” and “large” fiberglass tanks, and either size might be originally fitted by the factory to any size Maico (e.g., the small one was not “the 125 tank,” and might come over from Germany on any machine, up to the 501). As even the large tank held scarcely a moto’s worth of fuel for a thirsty big-bore engine, replacing Maico tanks was common. Several very well-made American fiberglass and plastic tanks were available from The Fiberglass Works, Mom’s, Cycle Craft, Superstar and Cole Brothers, to name several specialist firms. These tanks usually approximated the original factory angular design, more or less, but in a few cases bore little resemblance to the factory tanks—particularly the very large replacement desert tanks. A small coffin-type, nylon/ABS-like plastic tank, bolted to the frame via an up-through-the-tank bolt, was a cheap and indestructible replacement for the smaller bikes, at least. This unit was referred to in period advertisements as the “CZ-Maico type” tank, not marked with a manufacturer name, and sold by Superstar and Cycle Works (see figure 51).[6]

The large OEM fiberglass tanks attached to those Maico motorcycles imported by Eastern Maico Distributors from Germany in 1973 nearly all leaked when new. The problem was likely due to extremely bad quality-control at the factory, which might have been a function of poor labor relations or systemic oversight. These motorcycles were all retrofitted at Moore’s distributorship with fiberglass tanks manufactured by Bondurant Products to Moore’s specifications.[7] The Bondurant tank’s shape was a synthesis of that of the stock Maico units and of Ake Jonsson’s alloy 1972 works tanks. Jonsson’s tank is representative of the units that most Maico factory riders of the period 1970 to 1974 used. The tanks were constructed by German craftsmen, close to the Maico factory, to the specifications of the riders commissioning them. Maico riders Adolf Weil and Willi Bauer, among others, used tanks similar in appearance to Jonsson’s.[8]

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here.

In our next look at the history of motorcycle sport in America, we’ll examine a small Maico dealership in northern Pennsylvania. Miller “Gig” Hamilton was a racer and dealer who is not only representative of the local dealerships who sold European motorcycles during the motorcycle boom, but was also a personal friend of rocker Chuck Berry! See you then!

[1] Rake on a motorcycle can be described as fork angle, relative to the vertical. Rake affects several aspects of a motorcycle’s handling. (Bicyclists consider rake as fork angle relative to the horizontal.)

[2] Moto is one of two or three heat races from which the final standing in a motocross race is calculated.

[3] Interview with Dennie Moore by David Russell. Swede Ake Jonsson, who will appear as a brief but key figure in Maico’s history, was a graduate engineer who employed not only extreme physical conditioning, but also no small amount of science in his quest to win.

[4] Wheelsmith apparently supplied a kit featuring a new air box back-section, which the buyer could adapt to his shortened stock air box. Figure 45 shows a modified air-box which may incorporate this kit.

[5] Motocross Action, “Race Test: Maico 450,” Motocross Action (December, 1974), 43.

[6] Maico and the Czechoslovakian CZ were developed in neighboring countries and came to share several similarities. Not only did later CZs incorporate a coffin-like fuel tank design very much like Maico, but the two companies’ machines evidenced a similar rough, utilitarian look. CZ is given credit, along with Maico, of being the first two-stroke off-road motorcycles to displace the large, heavy four-strokes in the mid-1960s. CZs were heavier than Maicos, but have similar engine characteristics and were well-machined and known for their strength and reliability. CZ, like BSA and Husqvarna, was originally a weapons manufacturer.

[7] The leaking fuel tank fiasco between Eastern Maico and German Maico in early 1973 was one of the final, pivotal issues in the factory’s abandonment of Moore. German Maico later agreed to send Moore a shipment of motorcycles in payment for his expenses incurred in fixing the leaking tank problem, but then claimed the shipment was a standard delivery and that Moore never paid for. The factory used this argument against Moore in later legal proceedings (see chapter 4.2, “Eastern Maico, Part 2”). Bob Bondurant was an American race-car driver and racing product fabricator.

[8] Interview with Wilhelm Maisch Jr. by David Russell, (date not recorded) 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg), and interview with Dennie Moore by David Russell.