No products in the cart.

Maico, Motorcycle Culture, motorcycle restoration, Uncategorized

Change is Good: Motorcycle Personalization, Modification, and Performance Upgrades

Vintage Motor Company is pleased to present a three-part series on why Maico riders modified their bikes–and why owners of motor vehicles are still motivated by the same desires

The pick-up truck bounced into an open dirt patch on the Pennsylvania hillside. It came to rest abruptly; a drawn-out scratch of the emergency brake finalized its arrival. As the dust cloud cleared, the door creaked open as the driver took stock of the environment, then was shoved forward, bouncing back a bit from the door hinge stops. A short, muscular man, he jumped out and walked deliberately to the back of the truck. He kept his eyes aligned with his direction of movement and did not acknowledge the slightly interested glances of those parked on either side. The muted sound of un-muffled two-stroke motorcycle exhausts wafted up from the valley.

In the bed of the pick-up was a wooden shipping crate with German markings, which he pried open with a crowbar. Once the top and side of the crate were removed, a yellow motorcycle became visible. Several onlookers stopped to watch. The short man, sweating now, kept tearing apart the slats, still not meeting the interested glances of the gathering crowd. In about 30 minutes he had the forks and front wheel in place, and brought the brightly colored motorcycle down a ramp to the ground. He sloshed fuel into the tank; some spilled over the yellow paint and onto the ground. The bike leaned over at a tremendous angle, seemingly straining the long kickstand and threatening to flop on its side. Still ignoring the gathering bystanders, the man checked the oil levels and adjusted the chain. Kick, spin, kick, spin, kick, b-b-b-brRRAAPP! The yellow motorcycle roared to life, then settled down to a bRRAAP-ap-ap, bRRAAP-ap-ap, bRRAAP-ap-ap-ap, as hidden, carbon steel parts warmed up and infinitely-small tolerances changed for the better.

“Whadaya gonna do with that thing?” someone yelled.

“Gonna race it and kick your butts!” came the man’s reply.

The stocky man was Eastern Maico distributor Dennie Moore (posthumous article here) , and the motorcycle was a brand-new 1970 Maico 400.[1] Normally, no-one would race a motorcycle fresh out of the crate—something the incredulous crowd knew full-well. Yet Moore did successfully race the brand-new motorcycle in that day’s program, completing his promotional stunt and confounding the crowd’s understanding of what was possible. His point was that the Maico was a racing motorcycle that needed no changes in parts or design. It was ready to win, as delivered—without the modification required on all the motorcycles the crowd was familiar with. Granted, Moore would later describe the elaborate detail with which motorcycles really should be prepared–by attentive riders who wanted to finish races and have their machines last. But, stunt or not, Moore was correct: the Maico was capable of being ridden and raced successfully, “out of the box.”

Really ready to race…or “Maico-break-o?”

This is not to suggest that Maicos were always designed and built with the best care, the most up-to-date technology, or faultless manufacturing practices. These high-performing motorcycles certainly needed dedicated maintenance if they were to last: “Maico-break-o” was already part of the dirt bike community’s lexicon. Maicos were also temperamental and could be difficult to maintain at peak efficiency, particularly with respect to the engine and carburetion. Still, the Maico was generally well-designed and properly-equipped for its purpose . . . perhaps even incurring some of its annoying operational and maintenance traits as a result of being built to such a higher level of performance (a “thoroughbred, not a plow-horse”?[2]). Like the exotic car or aircraft, higher levels of engineering, design complexity, and performance certainly don’t lessen maintenance requirements. Such high-performing devices actually demand much greater attention, if the machines are to be kept operating reliably and safely at these higher levels. Performance comes at a cost, in both dollars and maintenance hours.

The motorcycle press during the early 1970s sometimes portrayed the Maico as a very expensive unfinished package—though one with enormous potential. Admittedly, parts such as the slippery foot pegs, the easily-flooded Bing carburetors, minimally-effective brakes, self-loosening engine bolts, and easily-bent steel rims deserved criticism. For a motorcycle costing nearly twice that of the Japanese machines—which, even if they didn’t handle or produce power as well as the exotics, were reliable when ignored—these problems stood out. Was the Maico a superior machine; able to compete and ‘win, out-of-the crate?’ Yes. Could it be improved and made more reliable, better-performing and easier-to-live with? Again—yes.

In this and the next two essays, we’ll discuss modifications and after-market parts and accessories which were employed on Maico motorcycles during the late 1960s through the early 1980s. This will provide an analysis of the period practices and habits of Maico motorcycle owners, and the reasons behind what they did. Most of these additive and modification practices were simple, rational responses to mechanical and environmental conditions. The examination of these practices will enhance understanding and awareness of the machines as they were used (versus as they left the dealer’s floor). At the same time, our examination will reveal other thought processes active in the sport motorcycle community, to include self-expression and attitudes about quality. It is important to note here that the riders in the 1970s were taking part in an older but still-evolving tradition. The changes which Maico users implemented reveal something of who these men were, and what practical or other motivations prompted their actions. We can see that Maico was never a default choice for the average motorcycle buyer. There were many other brands which were cheaper, easier to maintain, more reliable as an occasional rider, and more readily available. Buying, maintaining, and racing a Maico–as well as a Husqvarna, CZ, or other “exotic”–meant making a series of conscious choices and proclaiming a certain “I’m serious!” intent, which other riders understood by virtue of the machine’s symbolic significance. Modifying an expensive racing motorcycle was likewise a conscious choice with underlying meaning. The Maico, as we will see, was symbol for quality and dedication; it was evidence of the buyer’s commitment to the sport and his understanding of its requirements. The man who purchased a Maico was likely a focused competitor.

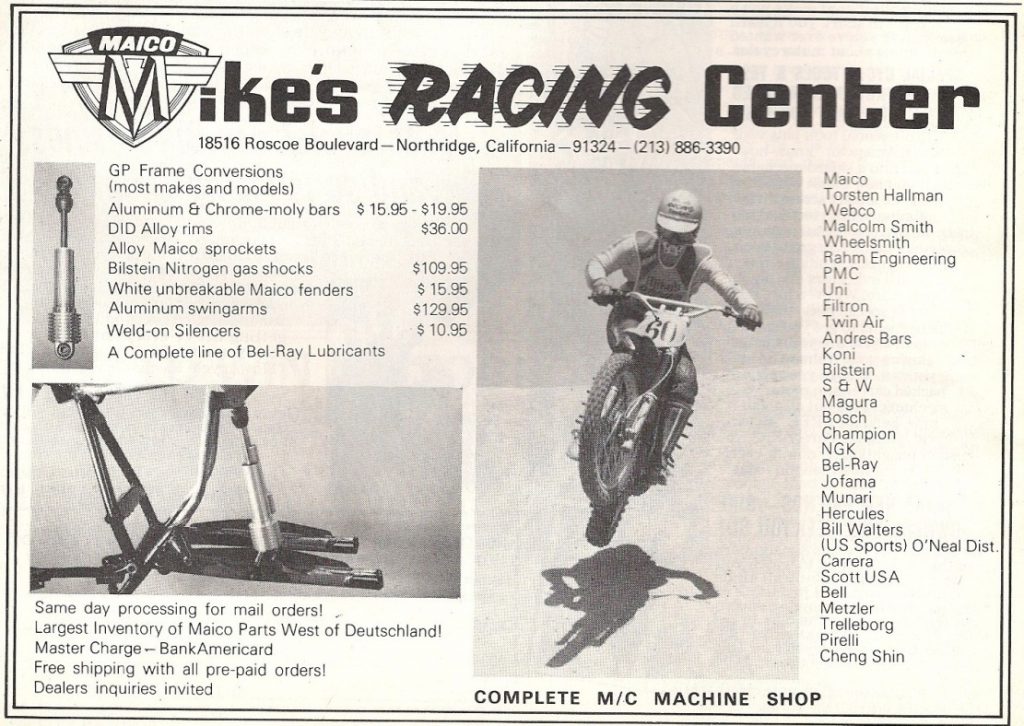

Throughout this article are references to ‘Wheelsmith.’ Wheelsmith Engineering (later Wheelsmith Motorcycles) was a Santa Anna, California, company founded originally in 1970 by two unemployed aerospace workers—and motorcycle enthusiasts: Sam Wheeler and Greg Smith. Wheeler left soon after the company’s founding, and Smith elected to remain with the business. While Smith initially produced performance parts for a variety of recreational and sport vehicles, it was the company’s association with Maico motorcycles that was the strongest. German Maico quickly realized that these particular California enthusiasts were more than flash-in-the-pan opportunists: a number of Smith’s modifications so impressed Maico management that they were put into production in later years. Wheelsmith, like other of the companies that will be mentioned, made components for Maicos which not only worked well, but indicated that the owner of a “Wheelsmith Maico” was an “insider” in racing circles—a man who truly knew what did and what did not work well, and for whom intense competition was a priority. Wheelsmith’s ability to add value to a Maico motorcycle, in multiple ways, was considerable.[3] (Note: we’ll discuss Wheelsmith in detail in a future essay.)

Aluminum and aluminum-alloy; its history, use, and value.

Aluminum, as the material from which most of these added-on high-performance items were made, also deserves an introduction. This now ubiquitous metal is a fairly recent discovery in the world’s industrial history. The extraction of aluminum from the earth had only been made practical in the early 1800s, and it remained rare, rather expensive, and still in search of a use in the first half of that century. It had not the inherent glow and allure of gold or silver, but was noted for its light weight. Aluminum refining was greatly advanced by Henri Sainte-Claire Deville in the mid-1850s, and it was initially combined with other, more beguiling metals to further its appeal as a basis for decorative objects. As refining costs continued to drop, the metal became the material of household accessories for a time; the curious dull silvery substance still not matched to a real purpose. It was not until the 1900s and the new age of transportation design that aluminum began to find its true–and perfect–place. In this application, aluminum’s light weight, malleability, high conductivity of heat and electricity, low melting point, ability to be alloyed with other materials, and non-corrosive qualities all made it an ideal material for many uses in trains, boats—and especially aircraft.[4] As World War II dawned and the world re-armed, the need for aluminum was critical, and all armed states struggled to ensure they possessed an adequate strategic supply. Access to aluminum, especially for aircraft production, was essential to the Allies final victory over Japan and Germany.

Following World War II and industry’s refocus on peacetime [mostly transportation] production, aluminum remained in demand for these same reasons. It was also beginning to be widely understood as synonymous with high-end mechanical performance. The prevalence of aluminum in war material was not lost on the young men who returned to civilian life after their service. These were the same men who would fuel post-war motorcycle interest and reinvent American motorcycle culture in the late 1940s. We have seen that the quest for speed and performance became all-pervasive in the United States after the war, and the use of aluminum—to reduce weight—was an obvious ally in this pursuit. Even beyond its obvious qualities of lightness, strength, and relative resistance to oxidation, aluminum expressed modernity and optimism like no other substance. It had become the material with unlimited technical possibilities; a space-age symbol of what was progressive and on the horizon of the peaceful, futuristic world to come.[5] Re-focusing on motorcycles, we see that by the end of the 1960s, aluminum (and aluminum alloy) was very much associated by the motorcycling public with performance, or “trick,” to use a vernacular of the day—and by the motorcycle boom of the 1970s, anything aluminum was in demand.

For the motorcycle historian, a benefit to having knowledge of performance modifications is that these data assist both in determining dates of manufacture, and in speculating the probable riding history of a particular machine. For example, certain parts and modifications are fairly easily traced to particular time periods. And, obviously, the parts chosen can suggest probable use: a large gas tank and a Webco extra-spark-plug holder may denote a desert racer or trail bike, while a small tank implies motocross application. Finally, familiarity with modifications will help in determining the originality of a machine. The historian will be equipped to de-code the symbols and meanings of these alterations, once provided with a bit of background explanation.

Americans as born customizers

We might also remember that while modifying motorcycles and automobiles has been a world-wide practice since motor vehicles were invented, Americans are certainly among the most noted customizers. This practice is especially visible among certain groups. Among the more famous communities are the Chicano-American ‘lowriders;’ hod-rodders of all varieties; the motorcycle chopper and ‘theme-bike’ builders; and ‘art-car’ devotees, whose lavish decorative paint schemes aim at a purely aesthetic statement.

So, when considering the modification of a Maico—or any industrial object, in an American context—we should remember that we are speaking of a nationality with a seemingly innate desire to change and re-create both themselves and their environment. Alex de Tocqueville noted the propensity of Americans to modify their European-made machines, while observing the young United States in the 1830s.[6] Americans cannot seem to sit still or let anything alone—it must move and change, as we ourselves work hard and move incessantly forward.[7] Even today, Americans purchase a new motorcycle and, in many cases, then pay hundreds of dollars more for after-market ‘high performance’ exhaust systems and other major parts. [8] They appear to be stating that either the part already on the bike, designed and placed there by specialized engineers, is inadequate for their needs—or, they just cannot be content to leave things the way they are. (Ever wonder how the buyers of new motorcycles realize that the major manufacturers are all incapable of making a good exhaust pipe, and it takes DG or Pro Circut to do it right?) Surely these compulsive customizers realize this, but yet they continue to alter and personalize their machines. Their cars and motorcycles need to look different from those of others; they enjoy conveying to onlookers that this is not just a machine, but their machine. In the 1960s and 1970s, the hop-ups and alloy pieces Americans added to their cars and motorcycles might not significantly improve anything in terms of ride, but they certainly conveyed meaning. Interested observers considered a hopped-up car or motorcycle as necessarily better–or, at least, more complete–than an unmodified one, and the total appearance of the machine was critical. We will see that performance and aesthetics were equally important to American motorcycle enthusiasts.

American motorcyclists: Modification, Personalization, and Meaning

Americans riders personalized their motorcycles from their first exposure to the new motorized contraption. In the first years, the early 1900s, this was a response to rapidly advancing technology, and also an acknowledgement of environmental conditions or their particular expectations for the machine. That is, as the motorcycle industry developed new accessories such as brakes, better carburetors, clutch drives, lighting, and electrical generating systems, motorcyclists added these items to their older motorcycle. They also modified the motorcycle to suit their use: Would it be carrying passengers, and need an extra seat or sidecar? Perhaps it would be raced, and therefore be lightened by removing fenders and other unnecessary parts. Besides attaching extra lights, leather fringes, and the like, these changes were most always very functional in the pre-World War II period. Immediately after World War II, with the tremendous newfound interest in the motorcycle, the act of significantly modifying one’s machine in both the pursuit of higher performance as well as how it looked became much more common. The practice of “bobbing” one’s motorbike, attributed to returning American servicemen, became fashionable.[9] Making a “bobber” started as a subtractive practice: removing excess metal and parts to reduce weight and better avail the bike to what power it could at present produce. Adding other, better performing parts immediately followed. The idea of performance became a fundamental aspect of motorcycle culture—if not its imperative.[10] The ex-servicemen’s modified motorcycles were similar to the airplanes, vehicles, and other military hardware they had operated for the past several years; stark, unadorned, and functional. These machines were highlighted by the natural attributes of unpainted raw metal alloys and the warm glow of exposed brass and copper.

Simultaneously, a visual aesthetic for the pursuit of high-performance was becoming recognizable. Before World War II, a ‘nice’ motorcycle was one in good condition; perhaps even with extra horns, lights, or other accouterments. After the war, the appearance of the leaner, modified, apparently higher-performing motorcycle attracted the attention of both riders and non-riders. The removal of unnecessary parts and the fitting of performance parts was visually synonymous with the new ‘performance’ ethos. Whether the work done and parts added actually did improve performance in any significant way was another thing; appearing like it did was at least an equal imperative for the machine’s owner.

In Britain, a culture reflective of the United States in many areas, including passion for motorcycles, post-war biker culture likewise coalesced into a more distinct, performance-oriented community. Young British motorcyclists in the 1950s, to their good fortune surrounded with lighter and better-performing native bikes than their American compatriots, nonetheless modified their Royal Enfields, Nortons, Triumphs, and BSAs. Longtime British motorcycle culture participant/observer Mick Duckworth describes this process, in its outermost, most superficial layer, as a desire for increased speed and performance, but also as a quest to create a “personal stamp”—to establish an identity for oneself, in conjunction with the machine’s appearance.[11] In Great Britain the “Rocker” culture of low-slung, high-performance “café racers”, equipped to do the “ton” (achieve 100 mph on public roads) proliferated. The desire for an outward ‘appearance of performance’ remains, highly integrated with the innate quest for self-expression on the part of the builder. For most motorcyclists these desires are inextricably entwined. These became and remain hallmarks of motorcycle culture.

The modified motorcycle: something to be corrected, or appreciated?

Beyond performance, we appreciate these alterations and personal expressions for their own inherent creativity, beauty of execution, and historical context. Although many antique automobile and motorcycle restorers have long avoided and “corrected” non-stock modifications to their machines, there are some good reasons to retain, preserve, and appreciate these modifications. This latter practice of acceptance of period modifications permits a deeper insight into the machines’ design and limits, and also grants an understanding into the way men in a pre-computerized world responded to challenges and problems. In the particular case of Maico, suspension changes made to the early-to-mid-1970s models (when Maico pioneered long-travel suspension, and improvements appeared monthly on the international stage) can be particularly interesting.[12] Maico owners were among the first riders to experience and benefit from this new concept in suspension. Since many Maicos in the early 1970s were modified to long-travel suspension configuration, either at home or professionally, motorcycles of this era are ripe for study by history-minded enthusiasts.

Most aftermarket parts applied to Maicos were manufactured by specialist companies, and then purchased and installed by the owner. Although some modifications were home fabrications by the owner/builder, this was not the norm. Maico, like most other motorcycle manufacturers of the day, did not venture far into the production and sale of accessories for its own motorcycles. (Perhaps the Maisch family thought that, after offering high-performance motocross and enduro models to the consumer, they had covered the bases. After all, if a the engineers discovered a part that worked better, they would have put in on the motorcycle, in the first place!) The Yamaha company was a notable exception, producing its own line of higher-performance parts—the G.Y.T. (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) line for Yamaha machines. Through the provision of these “hop-up” items, Yamaha recognized and moved to meet American consumers’ desires to customize. (Also, we should note that the early G.Y.T. parts addressed the fact that the company was lacking in competition-ready bikes.) In the process of offering custom parts for their machines, Yamaha also countered some of the attractive reputation of the European brands—Maico, CZ, and Husqvarna—and enjoyed being “blank canvasses” for the many custom G.Y.T. options available.

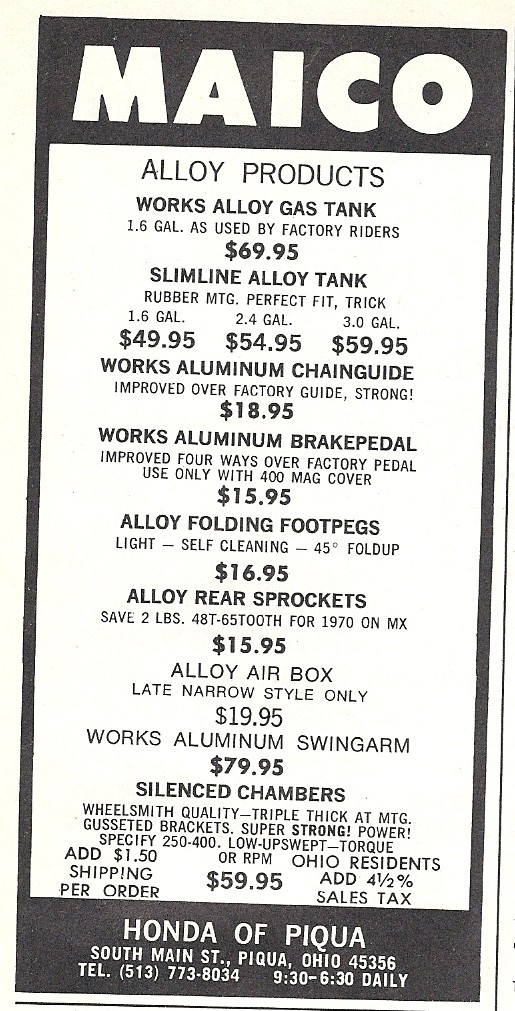

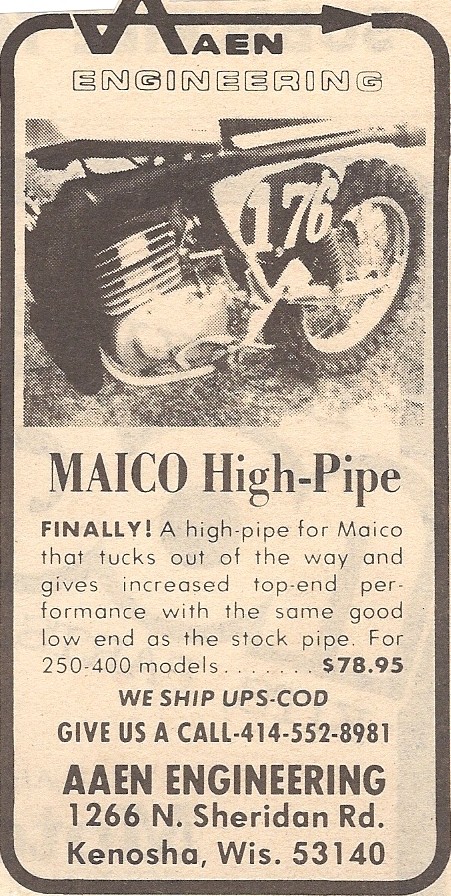

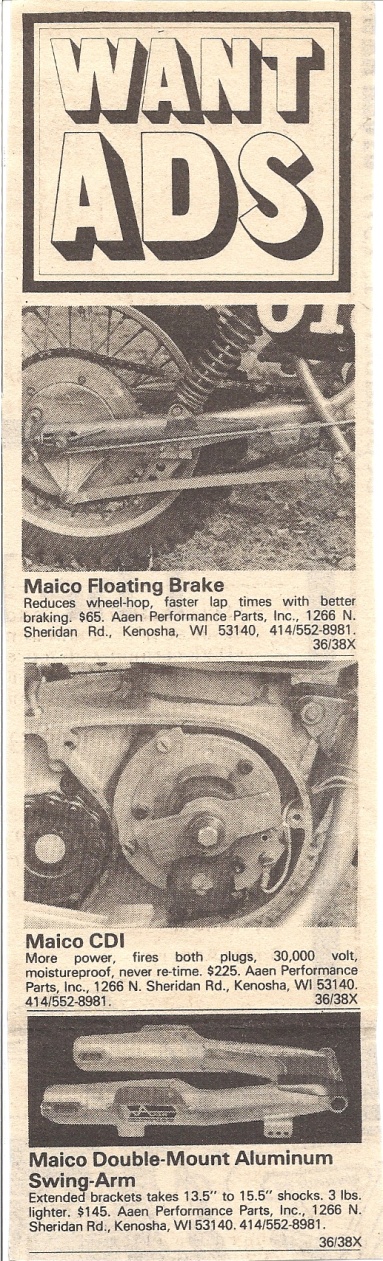

Yamaha aside, the ability of the independent parts builders–like Wheelsmith, FMF, Webco, and others–to dominate the custom parts market was due to the increasing coalescence of the motorcycle community, which was being bound together and connected by the many motorcycle magazines which emerged in the 1960s. This existing network enabled small companies like Wheelsmith to communicate with customers, and then deliver the products via the United States Postal Service or from the stock of a local dealer/distributor.[13] In the pre-digital age, the worlds of publishing and surface mail allowed for a tightly-knit, widely-distributed national community. Thus, when the motorcyclist saw the need for a better part, he had the choice of whether to fabricate the part himself (as in the early days), or to simply buy the shiny, new, good-looking and peer-accepted creation in the ads, either from a retail motorcycle shop or by mail order.

The parts suppliers directly advertised in periodicals such as Dirt Bike, Popular Cycling, Big Bike, Cycle World, and the rest, and also advertised indirectly by ensuring star riders and teams were photographed and seen using their products. The special brake pedals, gas tanks, shock absorbers, or suspension modifications used by the winning riders were naturally taken by observers as being real performance-enhancing objects. With the presence of a peer community of sports riders—connected by the motorcycle media—a new specialty part from a certain maker had a good chance of being analyzed (and desired) by fans in post-race magazine photographs across the entire country within the next month.

Store-bought ‘Trick’ versus Do-it-yourself

The cycle newspapers and magazines were in fact very focused on the alterations and performance parts added to the winning bikes; these were called “trick” parts in the vernacular, and were always of great interest to readers and riders. If a star rider went fast using the part, it was probably worth the price. Buying the ‘trick’ part, as opposed to the fabricating it themselves, was often preferable, as installing the bought name-brand item immediately carried with it the cachet and elan of the manufacturer and its star rider users. (We might relate this to fashion: Would a woman rather not wear a Dior or Halston dress, as opposed to an exact copy, made by her local seamstress?) This likely resulted in at least as good a part as what the individual could have made himself, and came with immediate name-recognition credibility. Certain heavy modifications, notably frame alterations, were performed by owners, according to guidelines publicized in the magazines, or as instructed by Maico employees.[14] The majority of Maico modifications, however, were additive, and not of the individual builder’s manufacture.

The impetus for these riders to modify and improve their motor vehicles, as we have noted, is rooted in two related motives: first, to improve the machine’s performance, and second, as a forum for the machine’s owner to express his understanding and discernment. These two desires may originate independently, but coincide and re-emerge in complex reflections and refractions of one another. Steven Alford and Suzanne Ferris confirm that customizing, as it pertains to the motorcycle, has existed from the sport’s earliest beginnings.[15] Alford and Ferris also note that whether the modification of the original machine is performance- or aesthetically-focused, the rider is still creating an “image of himself” with the modifications. To this end, he can express himself as the rider/builder of a fast motorcycle, the rider/builder of a beautiful motorcycle, or both. The rider/builder is, besides affecting material change for increased performance or enhanced aesthetic value, proclaiming that he knows how to affect this change: he has that “special insight” that only an insider possesses. To be successful (that is, to be accepted and approved by the cognizant observers within the culture), the owner’s speed- and performance-directed alterations must function simultaneously as both performance-enhancing and aesthetically-enhancing (well executed) to the overall machine. If not, the changes will appear superfluous or ugly, and the builder rendered out-of-touch. There is at work an unspoken, but yet strict and results-based judgment process. That is, the mounting of a high-performance head or brake pedal must perform its function at least as well as the old head or brake pedal; and must also perform aesthetically, within the overall form and visual statement of the motorcycle. Effective, successful modifications are defensible and stand as the self-expression of the builder/owner, reflecting the owner’s values and the skill of the builder.

Hey, Gear- Heads! Stay tuned next week for Part 2 of Change is Good: Personalization, Modification, and Performance Upgrades

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here. It also just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

[1] Interview with Dennie Moore by David Russell, March 27, 2007, Lewistown, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[2]MotorCyclist’s Great Bikes of the 70s, “Best of the Seventies,” MotorCyclist’s Great Bikes of the 70s (1981), 53.

[3] See chapter 4.4 for further discussion of Greg Smith and Wheelsmith.

[4] Sarah Nichols, “Aluminum by Design: Jewelry to Jets,” in Aluminum by Design, ed. Sarah Nichols (Pittsburgh: Abrams Publishing, 2000), 13-20.

[5] Paola Antonelli, “Aluminum and the New Materialism,” in Aluminum by Design, ed. Sarah Nichols (Pittsburgh: Abrams Publishing, 2000), 167-89.

[6] Alex de Tocqeville, Democracy in America (New York: Bantam Dell, 2004), 366.

[7] David Morris Potter, People of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American Character (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954), 55-60, 88-90.

[8] This statement is readily confirmed by observing any gathering of motorcyclists, and examining the myriad of aftermarket exhaust systems by firms such as FMF, TwoBrothers, Screaming Eagle, Vance & Hines, etc., on the motorcycles.

[9] Alford and Ferris, Motorcycle, 174.

[10] Mathew Drutt, ed. The Art of the Motorcycle (New York: The Guggenheim Museum, 1998), 198.

[11] Mick Duckworth, Ace Times: Speed thrills and tea spills, a cafe and a culture (London: Redline Books, 2011), 124-41.

[12] Maico’s role in the development of long-travel rear suspension, beginning in 1973, is detailed in several later chapters. Along with Yamaha, Maico shares the distinction of being the original test-bed for long-travel suspension. To Maico’s credit, however, the trickle-down flow of advanced rear suspension technology from the factory to the individual owner, both in the United States and around the world, happened almost immediately.

[13] In the early 1970s, most interstate parcels were delivered by the US Postal Service. Though United Parcel Service (UPS) had long been in business, interstate commerce regulations still presented significant restrictions for the company. Federal Express, founded in 1971, had yet to challenge the US Postal Service.

[14] Interview with Dennie Moore by David Russell. Maico factory riders, travelling the United States racing circuit, also served as conduits for the latest performance information and techniques from the factory in Germany or the racetracks in Europe.

[15] Alford and Ferris, Motorcycle, 173-4.

Thanks for the post!

My brother recommended I might like this web site. He was totally right. This post truly made my day. You can not imagine just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Wonderful that you discovered it and like it, William. My son & I appreciate the feedback–there’s a lot of work involved. And it appears you’re from good ol’ UK. We love your area, and I was fortunate to be an exchange student at the old Eton Hall College in Retford, back in ’78-’79. A beautiful land in so many ways!