No products in the cart.

Early Motocross, Early Motorcycle History, Gig Hamilton, Maico, Motorcycle Culture

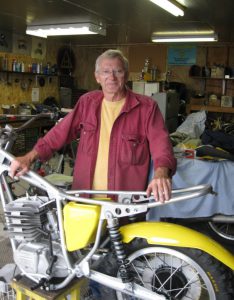

The Shop Owner: Gig Hamilton

An examination of the unique business model of retail sales, as the “motorcycle boom” of the late sixties and early seventies reached the United States. This was a time when hardware stores, used car dealerships, individual racers – and, nearly anyone with a few hundred dollars and some extra space – could become a dealer. This essay (Part 1 of 2) tells the story of central-Pennsylvania racer and Maico dealer “Gig” Hamilton. Hamilton was a close friend of early Maico distributor Dennie Moore… and also rocker Chuck Berry. Enjoy!

Introduction: The “Mom and Pop” Motorcycle Shops

The motorcycle business community of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States looked much different from that of the present day. In line with the “Mom and Pop” retail environment of a half-century ago, motorcycle retailers likewise tended to be smaller and more distributed across the American landscape. Prior to the sales domination of the “Big Four” Japanese motorcycle companies, and along with usually more established native Harley-Davidson dealers, small motorcycle businesses operated out of sheds and as a sideline to automotive repair shops in seemingly every American town.[1] Before the “box store” elimination of very small retailers—to include motorcycle as well as sellers of every other product and service—these tiny operations were the backbone of the motorcycle industry in America. It was a time when the purchase of a sign, a motorcycle or two, and a few parts could qualify an enthusiast as a ‘dealer.’ Once established as a dealership, the owner was able to purchase items at wholesale cost from the distributor and make a few extra dollars on the side, possibly also channeling the cost savings into his or his family’s own competition efforts. This liberal viewpoint on the part of motorcycle companies eventually disappeared; motorcyclists still recall Harley-Davidson’s forced dismissal of many older, stalwart, family-owned small dealerships in the 1980s and 1990s in favor of modern, luxurious mega-dealerships. But, throughout the rush by rival manufacturers to establish dealer networks in the vast United States market during the late 1960s and early 1970s, nearly anyone could become a dealer.

Eastern Maico distributer Dennie Moore performed one role in the motorcycle business: that of the importer/distributor. For him to succeed, he needed many hundreds of motivated retail dealers to buy his product, and to sell to and interface with the individual owner. If they were enthusiasts like himself, so much the better. Miller “Gig” Hamilton was just that example.

Coming to Life

Fresh spring air billowed up the building’s old plank stairwell. It was early April, 1964, and the first nice day in north-central Pennsylvania.[2] It signaled the end of another winter of dirty snow and heavy gray skies, and dingy trucks, careening down the town’s main street, kicking up vortices of coal and ice slush. A sweet, complex aroma reached the second-floor apartment and gently flipped a switch in the young man’s mind. There was something instinctual and elemental in the moment, resembling the effect of solar convection that was just then stirring a small turtle from hibernation in the nearby pond bank’s melting mush. The little painted turtle sensed spring; it slowly awakening and began boring out of the mud which had enveloped it for the last months. The young man sensed it, too, and peered down the stairwell. It was time.

Hamilton’s first attempt at moving 600 pounds of Harley-Davidson down the steep, narrow stairwell did not go well. Harleys were never known for cornering, anyway. The bike had come into the apartment in pieces: wheels, a frame . . . several boxes and a bushel basket. It was coming out fully-assembled. OK, pieces were going to have to come off. Lights, pipes, and front wheel are jettisoned. He tries it again; the bar ends still dug trenches into the old paint and horse-hair plaster. More stuff removed. Another try at clearing the upper corner. 136 pounds of teenager barely restrain over 500 pounds of Harley. At least the mass wanted to go in the right direction: down. Finally, the ’37 Harley was in the front yard; an hour later it is back together. And, it’s so pretty out. The buds on the trees, the warm breeze, smells of life—and the motorcycle. He should go for a ride. Gas; a little into both tanks. Will this thing start? (Did he get those cam gears meshed correctly?) Give the fuel a moment to trickle down. Big, sweeping, slow, sloppy-sounding Harley kicks. BLAAH-bluh-bluh-bluh. BLAAH-bluh-bluh-bluh. Then, the spark ignites the fuel mixture in one cylinder at the precise time—they say that with fuel, compression, and timing, an engine must run. Boy, are they wrong a lot of the time!—one explosion reluctantly following another. The big twin engine burbles down to an idle, with a few more adjustments to the carburetor, expressing itself as one big, burping, shaking iron hulk.

Ca-Clunk into first gear; let out the clutch, and the thing is underway. Each power-stroke of the old 1200cc iron engine pushes the Harley forward, faster. Two miles down the road, into the gorgeous spring smells, the 19-year-old hears the old engine sputter: running out of gas! He switches to the other tank for fuel as he turns the beast around. As home comes into sight, he hears the BRrap-puf-puf-puf-BRrap-puf-puf of an engine just about out of fuel. Finally, the big Harley does fall silent, and rolls to a peaceful stop in the cinders by the side of the country road. “Wow,” the young man thinks, as a bird ventures back to the roadside fence, investigating. It’s a 100-yard push back to the apartment, but well worth it.

An Introduction to Motorcycle Racing and Other Hard Work

Miller Bernard “Gig” Hamilton was raised by a single mother in rural western Pennsylvania, after his alcoholic father left home for good. Moving into the second-floor apartment after high school, the old Harley “basket-case” was his introduction to motorcycles.[3] He was hooked. Hamilton’s first job was at the local cigar factory in Philipsburg, Pennsylvania, maintaining the machinery. With his earnings he purchased a small 80cc step-through-frame Yamaha and began riding it through the woods. In the early 1960s, ‘scrambles’ racing was the predominant American motorcycle racing event. Hamilton soon found himself lined up on the starting line of his very first scrambles race with the little Yamaha. Being 20 years old, he had to obtain his mother’s signature to race—even though he was by then married and a father. His first race was a learning experience. Still putting his helmet and gloves on as the starting flag dropped, he got a late start, fell, got himself “all skinned up,” and was lapped. He “didn’t get lapped anymore,” though, after that first race.[4]

Hamilton soon progressed to a used, $50, very fast, and terminally unreliable Bultaco 125. After enduring the Bultaco’s self-destructive ways for a few months, a local dealer loaned him a 125cc Benelli to race on the dealer’s behalf. The Benelli was the complete opposite of the Bultaco; slow, but solid and reliable. Hamilton thought the calm Italian four-stroke was the best thing that could have happened to him as a racer. This was, he recalls, because it forced him to learn to finesse the motorcycle quickly through turns in order to pass other racers there; not depending on sheer horsepower and easy acceleration in the straights to win. “You win races in the turns,” he says. The wiry, aggressive Hamilton kept progressing, and achieved his expert and professional ratings quickly. Now, he qualified to compete for the purses payable to top finishers.

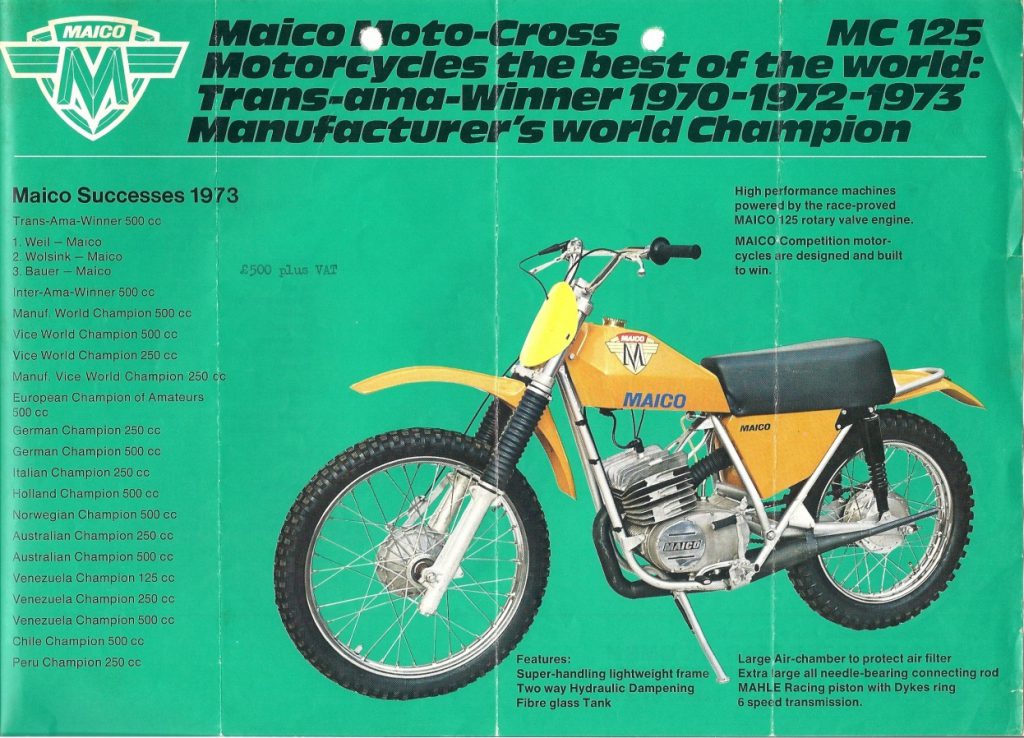

In the course of racing, Hamilton became friends with young Navy veteran Dennie Moore, from nearby Reedsville. Moore was selling and racing Hodakas at the time for the Aurands for Sports sporting goods store, but was simultaneously laying the groundwork for his own business: distributing a little-known German motorcycle, the Maico. Moore finished the application process after a few more months, and, with his father co-signing a $15,000 loan, began his Eastern Maico Distributors business in 1968. The first dealership franchise arrangement Moore arranged was with Gig Hamilton, up the highway in Osceola Mills, Pennsylvania.

Becoming a Maico Dealer

The young enthusiast, then working for an oil company, had set up a small shop near his home, first in Smoke Run, Pennsylvania, in 1964, moving a year later several miles away to Houtzdale. The requirements for becoming a Maico dealer in the late 1960s were minimal: “Buy one bike, and that was about all.” It seemed like a good idea; he could then buy parts at a discount and even make a few dollars selling to others. Hamilton purchased a new 400 Maico as his initial inventory, which he began to ride himself, and soon sold a few more Maicos to others. Hamilton also sold Hodaka, and briefly CZ/Jawa motorcycles. He worked 50 hours a week for the J.J. Powell oil company maintaining equipment and driving trucks, and ran the owner’s small Yamaha dealership when time permitted. In the evenings, Hamilton worked at his own little dealership. Like Hamilton’s Maico franchise, the Powell Yamaha dealership he managed for his boss was easy to come by, at the time. Hamilton recalls, “All [Powell] had to do to get the Yamaha franchise in the 1960s was to buy two motorcycles and $50 or $100 worth of parts and tools. And, of course a sign—actually, it was just a banner.” In contrast, becoming a dealer for a major manufacturer like Yamaha, today, involves a complex and lengthy application and approval process, many hundreds of thousands of dollars, and stringent standards.

Hamilton’s shop—H&H Cycle, named for himself and a fellow enthusiast, Dick Harvey, who loaned Hamilton $1000 for the enterprise—resembled the thousands of other small motorcycle shops then springing up across the United States. The sudden, tremendous growth of interest in motorcycling world-wide had triggered older and previously-smaller manufacturers to aggressively market their machines. The United States, of course, with its population and per capita income was the primary sales target. To gain access to this American market quickly, small or previously localized makers like Maico, Husqvarna, CZ-Jawa, Puch, Monark, Hodaka, and KTM made becoming a dealer in the states as easy as possible. The larger Japanese companies were nearly as compliant. While established dealers of the then-leading brands—Harley-Davidson, Triumph/BSA/Norton, and Honda, to name a few—took on the smaller brands on as a sideline, tiny “Mom and Pop” franchises sprang up overnight, as well. These family-owned, single-brand dealers often paralleled Hamilton’s situation, in that the dealership was not a primary income source, and served to facilitate the family’s racing hobby. In many cases the dealer also operated another business; perhaps hardware, welding/construction services, or a service station/garage. This arrangement was fine with the small brands, who wanted to penetrate the American market quickly, and in any way necessary. They could sort out the chaff, so to speak, later on. Japanese companies had begun heavily marketing their products in the United States several years earlier, and Honda, in particular, was already well established. Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki were hard on Honda’s lead, and their generally small, well-made, economical street motorcycles were becoming entrenched by the mid-1960s.

Hamilton continued working for the oil company during the day and operating his motorcycle shop at night. He was now repairing all brands, as well as selling and servicing Maicos. The salary for a blue-collar worker in rural Pennsylvania at the time was minimal, and Hamilton made only $2 an hour at his oil company job. He needed more money to provide for his family. Motorcycles were the answer. “I had to make money. I was driving to Ohio, because they’d pay $50 to win in dirt track—that was pretty good money in 1971. Pennsylvania tracks didn’t pay quite as much—$25 or whatever; maybe $50—if you were winning. In Ohio, if I’d win both classes I’d come out with a $100 bill. Not bad for a Saturday night racing. And you’ve got to remember that at the time I was making two dollars an hour, working for the oil company and running the owner’s little Yamaha shop. So, working 50 hours a week, I was clearing $80. I could make more money on one Saturday night [than I could working for Powell all week!”

Hamilton not only raced motorcycles, but snowmobiles as well. During the winter seasons at the time, these events could be especially lucrative. A weekend’s snowmobile racing for Hamilton could gross him $350—no trivial amount. To win on the big “sleds,” however, a racer had to be even more aggressive, and this could bring physical retribution from other racers. “You had to get into guys, and hit them; get right out on that ice. It was pretty dirty racing. I was always the smallest, shortest rider, running against these other guys, all big men. I remember getting into so much trouble . . . being small really saved my butt. They’d come over to my pits [and threaten me]; I’d keep my helmet and gear on all night long, especially at the outlaw races.[5] One time this farmer—I’d nailed him on the inside, put him out over the track . . . he came over. About six-foot-six and 300 pounds, screaming at me, me with my helmet on. He’d say something, and then hit me on the head with his finger each time. (I think his finger was the size of my arm!) This would happen all the time. I was always protested for hitting guys. I actually made extra side panels and took them with me, so that when guys would protest [and look for paint marks on the side panels of the sleds, to prove I’d hit them], I’d put these other panels on [to hide the evidence]![6] . . . By the way, in snowmobile racing, if you won the points, it was a $1000 bill at the end of the year. Polaris paid me $1000, two years in a row for winning the points.”

H&H Cycle continued to grow, with Hamilton working his oil company job by day and the shop at nights and on weekends. In 1970 he moved to his present location in Osceola Milss, first working from one side of the shed in which his daughter kept her horse, and building his own building in 1973. It was not until 1978 that Hamilton felt confident enough to quit his regular job and enter the business full-time. With a family of four to provide for; wife, son, and daughter, the cost of living in Osceola Mills was thankfully low. Hamilton became known as a first-rate engine mechanic; local motorcycle shops found it was cheaper to send engines to him for repair, than to do the work in-house. In addition to engine work, he sold Maicos and used motorcycles, and did any other mechanical work that customers needed.

H&H Cycle is located at 136 Walnut Street, several blocks to the north of Pennsylvania Route 53, the main road connecting Osceola Mills with Philipsburg. The Hamilton house, a fastidiously clean double-wide, sits near the north-facing entry door of H&H, making the quest for a lunchtime sandwich easy. As small business owners would understand, it also made the trudge back to the office, for many late nights of work, all too convenient, also. Walking up the lawn and across the loose stone driveway, the visitor enters through a single door, to the right of the overhead door. On a winter’s day the shop is warm with the constant humming of a forced-air oil heater and the mingling smells of heating oil and engine lubricants in the air. In summer, the lubricating oil mixes with the scent of sweet cut grass and hay from the horse stall, next door. A too-noisy air compressor kicks on with a clank and a Buh-buh-buh-buh when a tiny pressure sensor gives it the signal.

The rectangular garage is oriented east to west. Walking in the entrance door, looking south, the visitor naturally veers right, over towards the counter, piled with papers and boxes. A telephone and other electronic devices serve to identify this as the heart of the operation. Notes are pinned and stuck to the counter and around the phone, connecting the little operation to other tasks; past, present and future. The counter holds small boxes of inbound parts, likely from large warehouses in distant metropolitan locations very different from little Osceola Mills. As was the case with Eastern Maico at the distribution level, the profit on parts and accessories sales is critical to the overall viability of a small shop.

Across the cement floor, against the south wall, sit the blasting cabinet, drill press, cylinder boring apparatus, hydraulic press, and other large shop machines. Motorcycles being worked on are parked on the floor, or held up by stands. The selection might normally include a modern dirt bike, a vintage dirt bike, and several nondescript “UJMs” (universal Japanese motorcycles)—whose styles change so often that it is hard to remember their model names. The UJMs work. They sell easily, they take men to work, they need fixing, and these repairs pay the bills. Along the west side sits the long, metal-sheeted workbench. 12 feet long, it holds various disassembled engines, pans of parts, oil cans, and tools. The shop’s only window channels natural light onto the bench, as it looks out on a scene quintessential to this part of Pennsylvania: little two-story frame houses across the street, an Orthodox church spire, a cemetery, and the hills beyond. Farther away, to the north and to the west, lay hundreds of square miles of the sparsely-populated hills of Pennsylvania’s northern tier, running on to Ohio. In past decades, it was the availability of these hills for riding that helped create tremendous interest in off-road motorcycles throughout Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and the New England states—areas which remain bulwarks of the sport.[7]

A line of motorcycles is arranged on the eastern side of the shop; Hamilton’s personal bikes, bikes awaiting pick-up, and bikes sitting because the owners currently lack the money to pay for the work. Above these motorcycles and behind the oil burner, a shelf holds trophies. Most are relatively new—from vintage racing—and a few are from the old days, when racing was more serious, and the winnings helped feed his family.[8] Some of the trophies are ridiculously large; five-foot-tall plastic, marble, blue and gold constructions, commemorating a win that only a few people would still remember. Hamilton chides himself for having the trophies sitting about: “Gotta get rid of this stuff; taking up space,” he says.

Visit us again in a few weeks for the conclusion of The Shop Owner, and the story of why rocker Chuck Berry is sitting on a Maico!

Click HERE to view our hand designed Maico 250 t-shirt in our shopping gallery. We’d love your support! I hope this essay has been enjoyable. We always welcome your suggestions and comments!

[1] The ‘Big Four’ are: Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki. In the United States in 2014, The Big Four account for about 50 percent of all new motorcycle sales, with Harley-Davidson accounting for the rest.

[2] Interviews with Gig Hamilton by David Russell, June 19, 2007 and April 7, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[3] “Basket case” is a motorcyclist’s term for a non-running motorcycle with pieces removed.

[4] Interview with Gig Hamilton by David Russell.

[5] ‘Outlaw’ races which were not sanctioned by any recognized organization.

[6] In racing, when one party believes a rule has been broken, that party files a “protest” against the alleged perpetrator. The protest is then investigated by the race’s controlling authority.

[7] New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio are several states with important links to the sport, past and present. Topography, population density, and proximity to eastern ports all influenced this relationship. New York was home to the Ossa motorcycle importer and a hotbed for flat-track racing and endure competition. Ohio was home to Penton motorcycles and always a popular racing venue. Pennsylvania was of course home to the eastern Maico distributor. West Virginia remains a major motocross racing venue, and is home to the respected RacerX Illustrated magazine. All these states continue to show notable interest in all forms of off-road riding.

[8] Vintage racing is the modern racing of older motorcycles. Vintage racing was very popular in the United States from the late 1980s through the present day, as riders from the 1970s restored old motorcycles and enjoyed their former passion once more.

I miss the “Real Motorcycle Shops” the smells, sights and sounds along with the comoradery. The mall like atmosphere of motorcycle selling stores of now days just isn’t real. It might as well be Nordstroms shoe department.

Frank, with the design almost the same–except for the colors of the plastic–I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference if it wasn’t for factory names on the bikes!