No products in the cart.

Uncategorized, Vietnam War

Examining the Myth of the Vietnam Veteran

Who gets to define a man or woman?

Who is permitted to evaluate the life and choices of a person?

And who is to be believed?

**Moving slightly away from The Vintage Motor Company’s main cultural explorations (motorcycles!), we’d like to examine a cultural event that effected all of us to some extent or another…

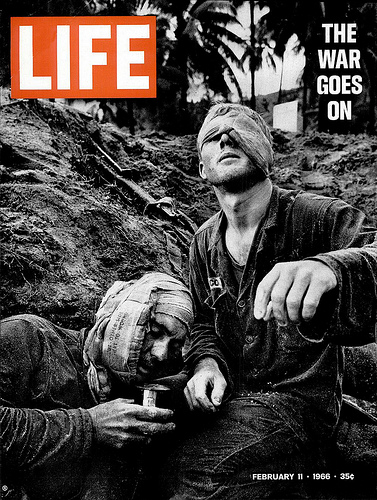

The War and it’s Usual Characterizations

One night in a Penn State University classroom, six class members gave their characterizations of the Vietnam veteran.

The first class member presented a written recollection and a personal film of Vietnam operations, shot and narrated by her brother; a former Marine helicopter pilot and now PhD. It was a literate, confident, first-person history, told by a knowledgeable and presumably well-adjusted and productive member of society, then and now.

The second class member told of her brother, a Vietnam veteran, highly-educated, yet unable to hold a job, scarred for life, and living as a recluse. She went on to state with assurance that “. . . and, you know, they’re all like that!” Heads nodded knowingly and sympathetically. Given the utter acceptance of her statement by the rest of the class, it was obvious at this juncture that the first-person account of several minutes before had already been discarded.

The third class member passed around pictures of her young father in Vietnam, along with three yellowed copies of a newsprint publication, VIETNAM GI. VIETNAM GI, we were informed, was evidence that the GIs were aware themselves of the “truth” about Vietnam. And, they were thus, even at the time, corresponding and communicating among themselves the major flaws of Vietnam involvement and the corruption of higher authorities.

A forth class member, a high school history teacher, discussed the works of writer Howard Zinn, whose experience as a World War II bomber crewman apparently granted him the insight and clarity to express the tragedy of Vietnam as it really was. Zinn allowed that the Vietnam vet was a generally honorable—if not misguided and victimized—pawn. Also mentioned in the mention of Zinn’s work was a split-second consideration of who, in fact, may have held the “moral high-ground” of the Vietnam experience. This certainly was not any American or allied personnel, but most likely it could have been the Anti-war Movement, the North Vietnamese Army, or maybe the Viet Cong—who may in fact be “freedom fighters” by certain definitions.

A fifth class member described his interviews with a Vietnam vet at his local soup-kitchen. This vet weighs several hundred pounds, and tends to beat his wife and get shot by police. His inability to fit into society appears to be a direct result of his extensive combat experiences as a “Special Forces” Marine in Vietnam.[1]

Finally, a sixth class member—also a teacher—described a favorite book of hers which she utilized to teach the Vietnam experience in class. It is written by a Vietnam veteran who lived to see the moral error of his ways (in that he did not more aggressively avoid military service). However, at least now he has had the opportunity to apologize to humanity (and the Anti-war Movement) by documenting the miseries he and his fellow soldiers inflicted on the Vietnamese people. In his book, the vet expounded in detail about the absolute wrongness of the war, and his participation in it. Without having to say the words, the speaker suggested that the author must certainly be correct; he was, after all, a Vietnam veteran. (Another class member and high-school teacher agreed with the importance of this book and noted that he reads the book annually for motivation.)

No-one disputed any of these ideas. Thus, I could only assume that the majority of my class believe—as I suspect the American people believe—that the Vietnam veteran is, at best, a misguided, uneducated puppet; likely a minority and prone to violence; and at worst a willing participant in the killing of innocents. He is, they are told, one who lacked the moral courage to not fight, and is now reaping the psychological damage resulting from his misdeeds.

Who is the Vietnam veteran? The long-haired vagrant in camouflage, wearing the boonie hat glistening with medals? Sociopath? One of purportedly “thousands” of disturbed Post-traumatic Stress Syndrome men inhabiting the Pacific north-west woods? War criminal? Hero?

Will the Real Vietnam Veteran Please Sit Down!

If one does not leave a definitive picture of himself, or ensure that others will correctly describe his legacy, the door is left open for others to define that person, sometimes suiting other agendas.

For perhaps this or other reasons, the definition of the Vietnam veteran held by society appears to be horribly wrong. Furthermore, we are not interested in finding the real veteran. Returning from Vietnam, the veteran of this war immediately found a generally apathetic—if not hostile—homecoming. He soon learned to downplay his war experience, even hiding it, to avoid prejudice on campus, in the workplace, and in society at large. A vacuum resulted, from the veteran not being asked his or her own experience, and not volunteering it, either. Any vacuum is soon filled, and the media, the anti-war movement, and the Left went about creating their own Vietnam veteran to suit their various needs.

Television media had, starting in the late-1960s, begun to cast the Vietnam war in a dubious, suspicious light. The war had, after all, been going on for longer than the nation had weathered World War II, but without pervasive indications of ultimate success. The seemingly endless conflict was indeed different for Americans. Eventually the inference of potential political and military ineptitude, wrongdoing, and impatience with the war became more interesting than the monotonous story of troops doing a tough job, day-after-day, year-after-year. In the early 1970s the movie industry sought to cash in on the war and Hollywood began to create the Vietnam veteran composite still in use, to a large degree. With John Wayne’s The Green Berets having been out for several years and considered comical government propaganda by anyone left of center, the first movies to follow the war’s end pictured a different kind of war and soldier. Apocalypse Now revealed a world gone mad, with equally-insane characters inhabiting a dream world of death and destruction. Marjoe Gortner’s drug-dealing, depraved vet in 1979’s When You Comin’ Back, Red Rider? stalks Hal Lindon’s innocent American everyman, until willfully creating the circumstances for his own destruction. The abused small-town Pennsylvania friends in The Deer Hunter lose their youth, values, and parts of their bodies in Vietnam, evolving by picture’s end into hapless victims, still unable to shed their pathetic love of the country that has lied to and abused them. Oliver Stone’s Platoon in 1986 showcased soldiers using drugs, abusing Vietnamese civilians, and murdering their own leaders. (Stone’s characterization, beyond the recognized artistic license of the other pictures, has been the one taken as “the truth” of Vietnam. Stone himself, a Vietnam veteran, actively promoted this interpretation. Burkett, reflecting on this creation, chastised Stone as someone who “had to know better (Burkett 44).”

Insight into the acceptance of these works of art as factual history can be gleaned from author Terry Anderson’s textbook, The Sixties. In the text’s closing filmography section, Anderson notes “. . . the metaphors and surrealism of what remains the finest Vietnam War film, Apocalypse Now. During the eighties, vet Oliver Stone made other important films, especially Platoon . . . (Anderson 229).” These personal and biased opinions are thus passed on as historic truths about the era.

Hollywood had some surprising assistance in creating the Vietnam veteran’s composite image. The Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), VietNow, the Veteran’s Administration (VA), and other veteran’s advocacy organizations adopted the theory of a “victim mentality” early on.

As the 1970s birthed the entitlement era, with seemingly everyone seeking compensation for some pain/wrongdoing/injustice—for which causal factors could be laid everywhere but on the individual—why should the Vietnam vets lose out on their share? Post-traumatic Stress Syndrome and Agent Orange were becoming household words for damage, and damage was necessary for compensation. A damaged veteran attracted dollars; a well-adjusted vet did not. Realizing this, the VVA and the VA found it both financially advantageous and necessary to subscribe to the emerging Damaged Vietnam Vet myth.

Oddly (and sadly), established veterans organizations like the Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion in some cases typecast returning Vietnam veterans similarly. These older veterans, shocked by both the elusive victory and the public condemnations, accepted too-easily what the media and Anti-war Movement were fabricating: a demographic of “drug-users, baby-killers, and (in the older veterans’ opinion) cry-babies.” Not lost on the World War II vets was the fact that they had won “their” war.

The realities of who the average Vietnam vet actually is are surprising to a culture which has so readily bought into the myth. Driven to action in the early 1990s while working to fund the Texas Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, businessman B.G. Burkett, an Army Vietnam vet, became so exasperated with the myths and falsehoods he encountered that he began what would become a 10-year project. In Burkett’s Stolen Valor, he analyzed many of the long-held and commonly accepted “truths” concerning the Vietnam veteran. These include the following:

*Vietnam vets wear old uniforms and hang out at memorial events.

In Burkett’s research, the vast majority of highly-visible “vets” (those often subscribing to the popular uniform of camouflage, medals, and long hair) are likely to not be Vietnam combat vets. Many, he has determined, have never served in the military at all. (Burkett initially became famous as the researcher who “outed” many supposed Vietnam combat vets, including celebrity cases such as actor Brian Dennehy, Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate Royall H. Switzler, and Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke.)

*Vietnam vets are often homeless, jobless, or underemployed. Burkett quotes research by economist Sharon Cohany, whose 1994 nationwide survey (Burkett 67) revealed the following unemployment rates at the time:

All U.S. Males, 18 & over: 6.0% unemployed

All male veterans: 4.9% “

Vietnam era veterans: 5.0% “

Vietnam veterans: 3.9% “

Thus, the Vietnam vet is actually more likely to be employed than members of other control groups. Further claims by Burkett (and observations by this author) paint the Vietnam vet as being generally more affluent than others in his age group on average, also.

*The poor, minorities, and the underclass were forced to fight the Vietnam War. Burkett notes that 80% of Vietnam veterans had High School Diplomas (vs. 65% of the same U.S. age group) and that draftees—who had a higher probability of being in combat—tended to have better educations and out-perform volunteers. As to the idea that minorities fought and died disproportionately to the population, the actual deaths, by race, are (Burkett 57):

% of total Deaths in Vietnam

5% Hispanic

12.5% Black

82.5% White

Burkett contends that these figures actually show that minorities were under-represented with regards to actual deaths in combat, compared to all draft-age males. This may in fact be due to a tendency on the part of minorities, often from poorer backgrounds, to actively seek training and service in technical and support specialties. Looking at the future, these practical young men saw the opportunity for the application of learned skills in the post-military marketplace. Conversely, white middle-class youths, not as concerned about later employment, tended towards adventure, joining the infantry, airborne, other more combat-likely specialties in greater numbers.

While “wealth” or socio-economic “class” cannot be readily determined from service records, Burkett makes a rough socio-economic conjecture by relating Homes of Record of service-members to regional per-capita income at the time. His results suggest that 30% of total Vietnam KIAs (Killed in Action) were from the lower 1/3 of American society, while 26% were from the upper 1/3—thus the wealthiest Americans do not appear to have been unduly sheltered (despite the anecdotal evidence suggested by college deferments). Or, it may also suggest that for every college deferred young man, there was at least one other of the same economic group that was willing to serve.

*Soldiers in Vietnam were constantly “fragging” (killing) their officers. Only about 230 non-combat homicides are recorded in military records (Burkett 63). A very small percentage of these incidents actually involved the killing of superiors.

Unlike the stereotypical image that most vets are still affected by the war, the veterans that I surveyed for this writing answered that, no, while the war was certainly a formative part of their lives, they frankly do not think about the war much, at all. All the veterans I spoke with wished to convey the idea that the real Vietnam vets are the ones “going to work, raising families, serving their communities . . . being responsible.” All realized and made note of the fact that there are certainly cases of Post-traumatic Stress and physical injures. However, they posited that while “. . . the guy with the boonie hat with ribbons on his dirty uniform and a pony tail” may look like the “real” vet, they most likely aren’t—and most made the point that no-one they know, in their extended circle of thousands of other Vietnam vets—would act like that, ever.

When asked about drug use, some vets concede that drugs were present and readily available, but using drugs while in combat was essentially unheard of. Others state that they never encountered illegal drug use during their tours of duty. According to these veterans, the need to have every soldier at the height of their abilities when facing potential danger (which drugs would obviously impair) was universally accepted. This overt threat would have been dealt with by soldiers themselves, as a hindrance to their own survival. One Army helicopter pilot stated, “Hell, if we found out that my guys were using drugs, I would have shot them myself! When you’re in combat, you don’t want the guy beside you stoned!” Mathew Rinaldi repeats a very different popular myth when he writes that “…drug use became virtually epidemic [in 1970-1972], with an estimated 80% of the troops in Vietnam using some form of drug”, and that “. . . by the end of 1971 over 30% of the combat troops were on smack (heroin).” (Rinaldi 52) While lurid and fitting the stereotypical image of drug use in Vietnam, as reflected by the aforementioned war movies (and perhaps justifying the use of drugs by those at home), Rinaldi’s assertions have little basis in reality, according to actual veterans interviewed. Though readily available and cheap in South Vietnam (a “party pack” of ten perfectly-rolled marijuana cigarettes could be purchased for $1 on most street-corners in 1969), barracks drug sweeps became routine by the late 1960s, and anyone caught was dealt with severely by leadership (and possibly by other soldiers as well, if the unit was in or preparing for combat). Drug use by rear-area troops was occurring at a higher level, but statements by veterans in Vietnam in 1969-1970 don’t support allegations of rampant drug use such as portrayed in Apocalypse Now, Platoon, and the image painted by pop culture.

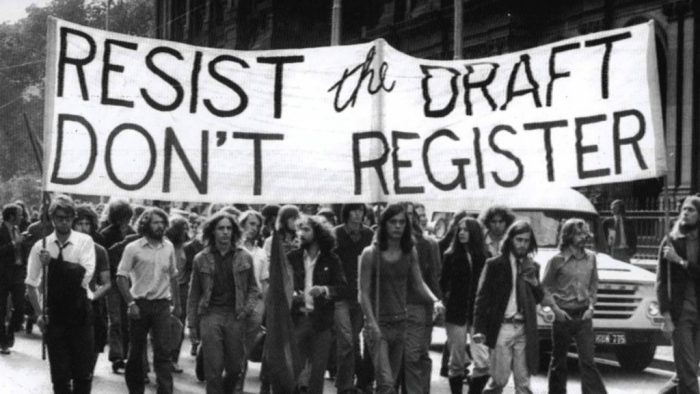

The “GI Anti-war Movement”

The American Left—both then and now—enjoys believing that there was a Anti-war “Movement” by disaffected soldiers and veterans during the war. This assertion helps to bolster the anti-war credo propagating the supposed immorality of the war and the moral superiority inherent in refusing to participate. They enjoy believing that a large percentage of Vietnam soldier were steadfastly against the war. An organization called, aptly, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, marshaled the credibility of actual disaffected Vietnam Vets to protest the war (John Kerry’s anti-war actions were as a member of this group). In reality, while individual acts of rebellion by active-duty soldiers occurred, and state-side organizing and acts of resistance were attempted by groups such as the Socialist Workers Party, the Worker’s World Party, and the American Servicemen’s Union (Rinaldi 5), such actions and any quantifiable success were invisible to soldiers.

VIETNAM GI ( the paper exhibited by a student) was created by veteran Jeff Sharlet, who returned from Vietnam disillusioned and was then very soon after rejected by the student movement (Rinaldi 4-5). VIETNAM GI first went to press in 1967, and consisted largely of wild-eyed claims of collusion by “the Brass” to wantonly expend soldiers’ lives in order to continue the war, the exposure of lies by the U.S. Government, and the general failure and pointlessness of the war. Far from being a communication vehicle for active-duty soldiers around the world, VIETNAM GI was so virulently anti-military that it obviously was not permitted by commanders on military installations. It was never heard of by the veterans I questioned. Publication ceased with Sharlet’s early death from cancer.

This is not to say that Vietnam veterans were enthusiastic supporters of the war—then or now. Taking two to four years out of one’s young life to risk it for a cause that person did not fully understand, was (and is) no more attractive to these men than to any other rational person. The difference between the vet and the deferred student/draft resister is simply that one party accepted responsibility to adhere to the dictates of his elected government, and one party did not. One had the courage to accept responsibility, and the other hid from responsibility—under the guise of moral courage—and left the next man in line take his place. From a larger strategic or moral perspective, the Vietnam vet largely takes an ambivalent stance on the war. Some vets are strongly supportive of the American government’s stated war goals (then and now), and some are equally critical of the same. The common uniting factor is that they all accepted responsibility for military service and found the personal courage to be a soldier.

The Depraved American Soldier and Freedom Fighters who Cut Off Heads

“Here’s to all the Draft Resisters, who will fight for sanity,

When they march them off to prison, they will go for you and me.”

-“Monster”, by John Kay/Steppenwolf, 1970

“The unspeakable and inconfessible goal of the New Left on the campuses had been to transform the shame of the fearful into the guilt of the courageous.”

-Tom Wolfe, 1982

A primary goal of draft resistance during the Vietnam war was to create, in the act of draft resistance and avoidance of military service, an ethical and moral superiority. Conversely, this side characterized the individuals who actually did summon the real courage to serve in the war as being their moral-inferior (Burkett 53). This strategy was, as Tom Wolfe noted, a ploy that could never be openly stated for what it was, yet remained the central driving motive for the resistor who simply (and perhaps quite rationally) wanted to avoid the draft and service (and possible danger). “Legitimate” conscientious objectors surfaced, and history shows that, as in other wars, many of these ethically-motivated resistors accepted military service as non-combatants (often as medics, potentially the most dangerous combat duty), while others accepted legal penalties including imprisonment for their choice (The veterans I spoke with harbored no ill will against such “legitimate” objectors—ones who resisted for true and previously-held reasons—and several mentioned Cassius Clay/Mohammed Ali as someone who “paid the cost” for his moral choice. Conversely, these veterans held no respect or sympathy for basic self-serving “draft resistors.”)

This need to transfer the cloak of moral superiority and courage from those who had actually earned it, to those who were not willing to risk their own time or lives (and allowed others to risk theirs, instead), contributed to the Vietnam vet caricature embellished by Hollywood in the 1970s. Mass media readily accepted the caricature, and Vietnam service became a ready post-script to any anti-social behavior. The Vietnam-service tag was added to crime descriptions and deviant acts, suggesting an obvious correlation between Vietnam service and later violence and non-appropriate behaviors.

In constructing the image of the depraved/damaged/immoral Vietnam vet, portraying the cause of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) as the moral high-ground in the war was attempted. Indeed, 1960s radical Tom Hayden likened the armed Black Panthers, the then-darling of the Left, as “America’s Vietcong (Collier and Horowitz, 12).” An awkward revision of reality was required, however, to overcome simple truths. For starters, the NVA had clearly invaded sovereign South Vietnam. Though the war was successfully portrayed as a “civil war,” the two countries had never been previously unified. Then, there was the actual track record of the VC and the North Vietnamese communists. These were ruthless fighters and power-seekers who had, in fact, executed and imprisoned several hundred thousand of their own people upon consolidating power in the north; they would go on to exact similar atrocities on the defeated South Vietnamese populace, beginning in 1975. Throughout the war, the VC committed never-ending acts of terrorism and torture upon the South Vietnamese people. Finally, revisionists ignore the fact that the majority of the South Vietnamese people did in fact support their government.

All these facts were obvious from the beginning of the conflict—much less after the barbarities which would follow in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, after the communists took over. Buoying the Left’s efforts to redefine reality was the press’ focus (not unlike the present day) on isolated and supposed American atrocities and the maltreatment of the Vietnamese people. Rare but real atrocities (notably My Lai) and the accusations and innuendo interpreted from press photographs (notably two very famous pieces; one of a young girl running after being burned by napalm, and the other of a Viet Cong prisoner being executed by a South Vietnamese police chief ), contributed to the public’s perception of the American soldier in Vietnam as the “Baby-killer.” Later, lurid assertions by veterans-turned-activists (notably the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and including ex-Navy Lieutenant John Kerry) strengthened this perception.[2]

A footnote to the Depraved Soldier myth—that of the VC and NVA being “Freedom Fighters”— has emerged over the past years. Tough, ruthless, often fearless,

eagerly adopting terrorist techniques, and [in the case of the NVA] good soldiers; yes. However, NVA and VC atrocities make this an extremely far-fetched analogy. Most veterans I interviewed found the comparison “obscene.”

Universal Guilt

Despite the belief among many that Vietnam vets suffer feelings of guilt about their wartime actions, the Vietnam vets I have known and interviewed exhibited no sense of angst concerning their service and actions in Vietnam. They are very proud of their units and both unit and personal accomplishments, and see these accomplishments independent of any greater U.S. policy or result. (This is entirely in line with 20th century American military scholar S.L.A. Marshall, who wrote that the actions of men in combat are almost entirely connected to the survival of and desire to support their friends; fighting for larger, abstract issues or beliefs is largely fiction.) All acknowledge that “their war” and they themselves have been given a negative image (and most have suffered personal prejudice or attacks because of it), but none feel anything resembling shame. They all state that, although the war was certainly a major event in their lives, they do not dwell on Vietnam. These veterans harbor no bitterness, although the treatment they received upon their return from Vietnam, along with continued misconceptions, has not gone unnoticed.

One veteran said of the National Vietnam Memorial: “I believe the . . . wall was more an apology than a tribute.”

Conclusion

The Vietnam veteran is not, in the vast majority of cases, a damaged, anti-social victim, nor is he (or she) less of a person for the experience. He is likewise not the potential killer on a hair trigger, the camouflaged malingerer on Memorial Day, the hapless social case, or Rambo.

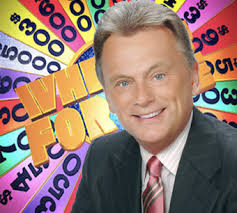

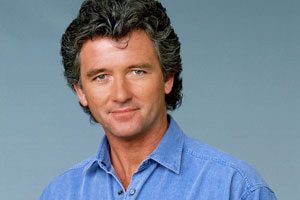

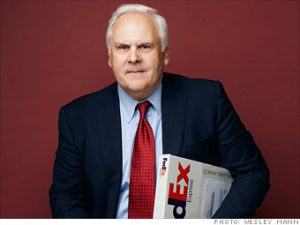

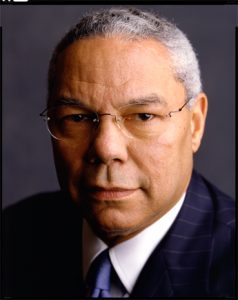

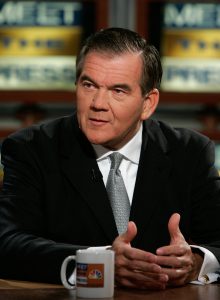

He is, in the cases I have seen, the businessman; the professional; the father. He is the responsible, normal person working and still serving others in some way. Now, nearly five decades from Vietnam, he is likely a retiree, waiting for the grandkids to visit. The Vietnam vet is statistically better educated and more financially-secure than his non-military peers, is proud of the job he did in Vietnam, and may vote Republican or Democratic. He is the product of the ultimate graduate school; he is an ex-General named Powell, Schwarzkopf, or McCaffrey; he is Frederick W. Smith (FedEx founder), Pat Sajak (“Wheel of Fortune”), Donald Graham (Washington Post publisher), Patrick Duffy (“Dallas”), or Walter Anderson (PARADE magazine editor). He is a writer named Philip Caputo or William Broyles. He is a member of Pittsburgh’s Vietnam Veteran’s Leadership Program because he realized he was in the position to help the real downtrodden—veteran and non-veteran alike.

He is, in short, likely to be (at the time of this writing, age 67) at the top of his career and in a position of professional eminence and power. In this respect he parallels and stands in contrast to the standing of those of similar age who did not do what he did or go where he went.

Perhaps the professions at present which hold the greatest number of power brokers of this latter group are in academia and public education. Since remaining in college meant perpetual draft (and service) deferment, many highly-educated individuals are products of the college deferment strategy. Furthermore, many of these individuals found their way into education, where they, likewise, are presently at the height of their influence (as a female Penn State professor and former Anti-war activist recently pointed out).

Samuel Johnson wrote in 1778 that, “Every man feels meanly of himself for not having been a soldier or not having been to sea.” Those who were presented with the challenge of military service during war and refused it, for reasons of their own convenience or cowardice, find themselves in Johnson’s quandary. They have had to rationalize their past actions ever since. They will continue to create justifications for their refusal to accept that challenge and duty until they die, cloaked in the peace movement’s convenience-based and quickly-discarded morality, contrived civil responsibility, or whatever form their varied explanations may take. Quite simply, those who served in Vietnam—whether they supported the war or not—believed that in a democracy, one did not get to pick one’s war. Those who avoided service, did.

Former draft lawyer James Dannenberg reflected in 2002 on how he and other energetic young lawyers succeeded in helping thousands of similar draft-age Americans avoid military service during the Vietnam years, mostly through the exploitation of minor loopholes in the Selective Service law. Dannenberg felt good about his efforts in “saving” these men from military duty and possible injury in Vietnam until years later, when he learned that he had had a cousin named Richard Marks. Marks had gone to Vietnam with the Marines, and was killed in Quang Nam in 1966. The thought occurred to Dannenberg that for every young resistor he succeeded in helping avoid service, another young man, somewhere, was required to fill that void. Ultimately, Dannenberg pondered, Did Richard go—and die—in my place?

Most disturbing may be that a younger generation of educators and academics have accepted without question, from their anti-war movement teachers, the twisted myths of immoral, damaged Vietnam veterans and selective national responsibility, and are readily passing these attitudes onto our children. We can hope that through time and rational analysis, this chain of falsehoods will deteriorate and break, under the scrutiny of coming generations.

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our shopping page located here. It also just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

Sources and Works Cited

Anderson, Terry H. The Sixties (second edition). New York: Person Longman, 2004.

Burkett, B.G., and Glenna Whitley. Stolen Valor. Dallas: Verity Press, 1998.

Collier, Peter, and David Horowitz. Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts about the 60s. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Dannenberg, James. “What I Did Was Legal, But Was It Right?” Newsweek (February, 2002), p19.

Monster. Steppenwolf. Record album. Dunhill Records, 1970.

Rinaldi, Mathew. “The Olive-Drab Rebels: Military Organizing during the Vietnam Era.” Radical America Vol. 8 No. 3 (1974).

Wolfe, Tom. “Art Disputes War: The Battle for the Vietnam Memorial.” The

Washington Post (October 13, 1982), pp B1+.

Interviews (personal):

Tenney, Robert US Army

Travers, John US Army

Smith, Scott US Army

Baker, Keith US Marine Corps

Burton, Jerry US Army

Interviews (written responses to questions):

Smith, Lawrence D. US Marine Corps

Pultz, Barney US Army

Le, Chieu Van South Vietnamese Air Force

St. Lawrence, Mitch US Marine Corps

Cronin, Robert M. US Army

Marcinowski, John E. US Army

[1] The Marine Corps has no “Special Forces” in the Army, Navy, or Air Force connotation of the word. Battalion or Force Reconnaissance, sniper teams, or special teams (Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Companies) might erroneously be considered Special Forces by some, but not by Marines.

[2] Kim Phuc, the naked, burnt young girl in the famous photo, recovered from the napalm (mistakenly dropped by the South Vietnamese Air Force), fled to the west, and currently resides in Toronto, Canada. Edie Adams’ horrific war image of the Viet Cong lieutenant being executed broke current-day media practices of not showing executions. It failed to relate the fact that the Viet Cong lieutenant had, the previous day, murdered a police officer and his entire family. Seeing the life of the police chief ruined forever for an action entirely within accepted rules of war, Adams supposedly regrets releasing the photo to this day.

Hello David, awesome article! Really great read! A quick response to it. My favorite Uncle Greg, now deceased, was in Vietnam in 1968, the year of my birth. He was the best, got married, had a beautiful daughter, worked for the New York City school system, and even employed me for three summers in my teens before the board of ed. wouldn’t allow family members to work for them. My father in law was in Vietnam also. He got married, had a son and a daughter(my wife) and worked as a carpenter for 35 years before retiring. He’s a pretty damn good guy. Every vet has their own story, some have had life issues to be sure. But my experience with vets are positive as I stated. NOT the way the left loves to portray them. Oh, by the way, my grand father was in WW2, and I wouldn’t be here without him! You, sir, are to be commended for a wonderful article that is not just a great read, but important! Thank you!

Hi, Eric, thanks for the endorsement. I, too, know a number of Vietnam vets. They are all hard workers, well-adjusted persons, of all political persuasions, and in the end, good people. They did a tough job and–at least the vets I know–are proud of it. It’s said, “You don’t get to pick your war” (or your hard times, for that matter). These men and women stepped up and did a hard job that was going to be done by someone; if not them, then another young person. For history to claim that the war protesters were the ‘true heroes’ of Vietnam is a travesty.

The war protestors and the soldiers were heroes and victims. The soldiers were called upon by the government to fight in a useless war, the protesters knew that. This isn’t to say that these soldiers weren’t brave as they did their moral duty after all and that couldn’t live happy lives after their service but the trust of the government was definitely tarnished by this event. Overall, I’m glad the experiences you’ve had with these veterans were positive.

David, your article was a truly wonderful piece, and the Vietnam vets I know are all successful and happy in their life. Like you have described, there are a very few “Hollywood typical” vets around, far outnumbered by the others who answered their call to duty and have since carried on with their life.

I had a friend who worked as a therapist and one of his first clients were Vietnam war veterans. So yeah not everyone shares the same experience like you said.