No products in the cart.

Tim Hart

Tim Hart, Revisited

Tim Hart passed away on March 6th, 2017. In retrospect, he was a hero to most every formerly-young dirt rider, who is now past the age of 55. He was the image of who we all wanted to be, those many years ago. The funny thing is that each of us kept this admiration inside, and nobody else seemed to know about it. It’s only now, as we compare notes, that we find that very many of us admired Tim.

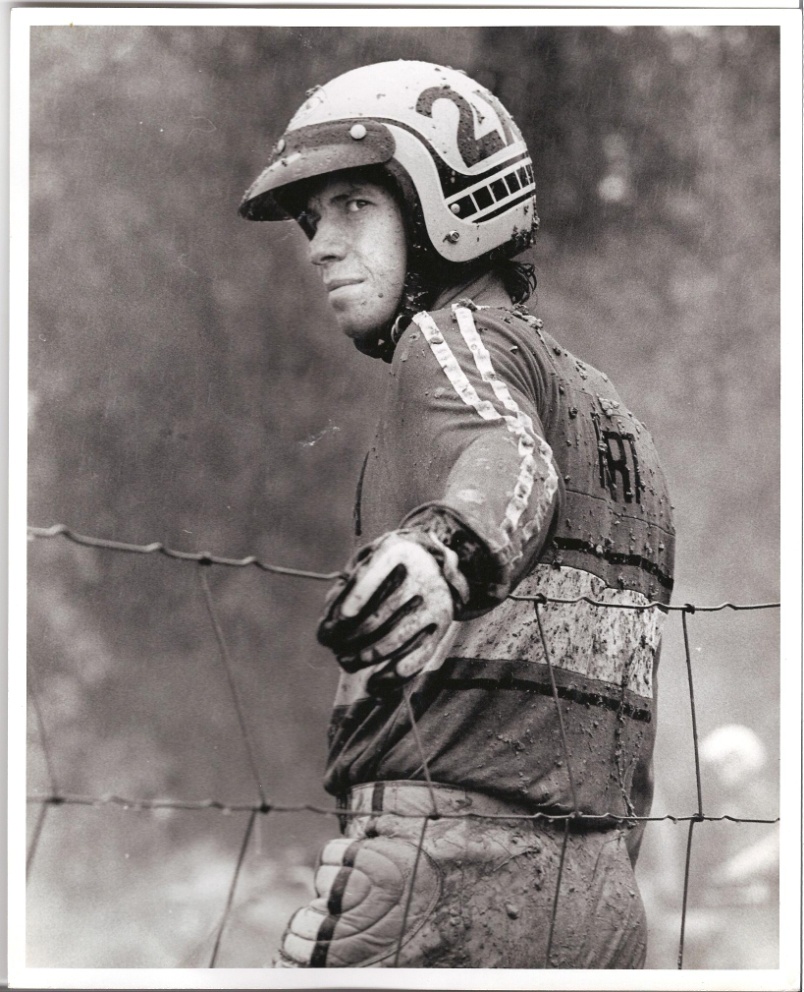

Considering Tim, I wonder if one of the most interesting aspects of his surprising fame, was, curiously, his anonymity. For years, as a boy poring over every detail of DIRT BIKE, MOTOCROSS ACTION, and the other off-road magazines, I never saw his face; it was always covered by that iconic striped helmet. He never seemed to appear in any head shot, where he could be recognized. The one photo where we should have seen his face, we didn’t. It was in DIRT BIKE, of course, and was labeled something like “Tim Hart, America’s best 250 racer, gives Brad [Lackey] a ride back to the pits.” A smiling, hair-in-the-wind Brad rides on the back of Tim’s Maico, but Tim himself is stays hidden under the striped helmet. Our masked hero.

Now, there were, no doubt, certainly many other motocross heroes; we all had several, and for our own reasons. Brad Lackey was one of mine, in those early teenage years. Back then, in the sixties and seventies, we liked what connected to us to people and things on a simple, direct basis. While Brad’s coolness certainly helped, I liked Brad because we both had Kawasakis.

This was the same loyalty that dictated that young males must be faithful to the brand of car their parents drove. (We were a Chevy family—as were the Obercash and King families. The Pecks and the Schorys, as I recall, were Ford people. Devotees of brands other than our parents’ became slightly suspicious to us. Not a few yelling contests and a few wallops on the head were born of this allegiance.)

Tim was on a Maico. Now, no central Pennsylvania boy attending Lower Paxton Junior High School rode a Maico (at least that I ever met; save one notoriously fortunate boy named Craig…but he’s another story). Many kids had no motorbike at all. Fortunate boys in our neighborhoods rode mini-bikes, be they Briggs & Stratton-engined things or higher-class Honda 70s. (Note: the parents who bought their kids Honda 70s probably all lived in “split-level” houses—the extravagant home design for “rich” kids back then, to my thinking.) If they were extremely lucky, they were helped by their parents in buying a Japanese enduro bike (I fell into this category). And, if they were gifted beyond reason, they had at their disposal an actual racing bike . . . and perhaps even raced it! But, as I have noted, no-one I knew, personally, as a young teen, was that lucky.

Tim’s mount only added to the glamour and his mystery. Maicos—like CZs and Huskys—were only seen in magazines. “May-co” even sounded meaner and more exotic than the others; probably coming to these American shores from some dark forest in Germany, (maybe even involving Nazis)—like Cuckoo clocks and Hansel & Gretel and all that stuff. Furthermore, Tim’s Maicos were the old “square-barrel” machines, which made them even more darkly mysterious. (The new “radial” models were supposed to be even better, according to DIRT BIKE, we could recite.)

The first time many of us saw Tim, sans helmet, was in the DIRT BIKE “Bench Racing Contest” special. There it was: The Photo. It may be, as I have previously suggested, the best portrayal of early seventies motocross ever taken. Long-haired Tim is sitting on the ground at an unidentified motocross starting line. Gary Chaplin is on one side (on a Maico), Gunnar Lindstrom is on the other (on a Husqvarna), and a beautiful blonde sits on Tim’s Maico. To overuse another of my previous descriptions, there was nothing in this image for a teen-aged boy not to like. Celestial perfection, orbiting around Tim. Now, there was a guy who had it made! I would have rather been Tim Hart than any astronaut or movie star.

We rode dirt bike in my neighborhood for a few more years, until late high school. Then, for most of us, other passions crept into our lives. Cars and girls supplanted dirt bikes in importance. We got jobs after school. Soon some of us went away to college, others to full-time, serious work. The DIRT BIKE subscription eventually expired. We moved on. Years—decades—passed.

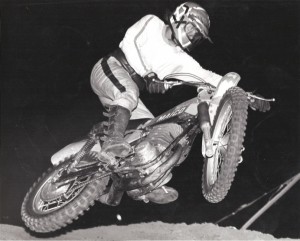

Yet it seems we never did forget that name and that look, lodging it in the beautiful, mysterious recesses of memory. Several publishers helped us to not forget, by using the DIRT CYCLE image (of Tim jumping the square-barrel) on repair manuals and other advertising. It was not until 2008 that, while working on a collection of oral histories relating to Maico, that I had the good fortune of being given Tim Hart’s contact information. I was elated! After contacting him, we spoke two or three times, with me collecting about two hours of recorded material. It was such a pleasure. First, there was the fact that I was talking to Tim Hart! It was also very apparent that my interviewee was just as excited about our conversations as was I. He bubbled over with joy in recounting his old racing days. He related everyday encounters that, to me, were simply incredible: buying leathers from Roger DeCoster; preparing to ride the Baja race with John DeSoto; winning the first 125cc World Championship. Separated by 3000 miles of American dirt and lives lived so differently, we were both in near-childlike states. Me, talking in person to the great Tim Hart, and him, recollecting details of that long-ago, romantic, on-the-road motocross life.

While utterly humble, Tim was very proud of his current work on the Long Beach docks. It had taken him many years to achieve his position as a longshoreman/operator of aerial cranes, he noted, and there had recently been a television special highlighting his facility and the massive cranes. At one point my wife entered in the room where I was talking and recording.

“Who are you talking to?”

“Tim Hart—the guy in The Photo.”

“Oh—he’s SO cute!”

Why was Tim so popular? Though certainly a national star in those early years, he won but a single National Championship—that 125 World Champion at Zoar, New York in 1974—not long before Yamaha let him go. That wasn’t the point, though. He was a winner and a motocross star, but his charm was something deeper than accumulated points.

As I suggested earlier, some of the popularity was, at least for those of us who never got to meet him, Tim’s enigmatic appeal—always hidden, under the wild red pre-Van Halen striped full-face helmet. Perhaps the mystery of who he was—to boys who barely knew who they were—brought us to identify with him.

His riding skill certainly played a part. Hart dominated SoCal racing in those early days, and always placed high in national events. Many remembrances of him reference his “riding the rail” through the turns. He definitely looked good in those old racing photos. I would have loved to have seen him ride; it must have been remarkable.

Ultimately, I believe Tim’s hold on our imaginations is mostly due to him being “one of us.” And, because he was who we wanted to be. The leathers, the helmet, the hair, the factory ride, the girl. He displayed the courage to do what we, if we had possessed the skill, would have signed up for in an instant. And we would have wanted to do it just like he did.

Tim was a workingman, as well. Again: he resembled a just-slightly-cooler us. A guy who could have lived down the street; somebody’s brother. Somehow this came through in the motorcycle press’s coverage. His was a practical, sparse, rugged American cowboy look. The leathers had duct tape keeping them together, the jersey was dirty, and the boots were worn. Here was no prima donna; no coddled 16-year-old supported by wealthy parents. And he did not offend: no peace signs, hot temper, or inebriation noted. No angry words in interviews. No issues with the law, crazy tattoos, burning American flags, whatever. You got the feeling your Mom would have approved of Tim.

He was just that guy, doing it exactly the way we would have done it. If only we could have.

Thank-you, Tim!