No products in the cart.

Early Motorcycle History, Motorcycle Culture, Uncategorized

THE MOTORCYCLE AND MAN: A SOCIAL HISTORY (BEGINNINGS, TO THE 1950S)

T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia,” 1888-1935) loved to ride his motorcycle. On a damp early morning in 1925, former Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence, now living incognito as the lowly Royal Air Force enlistee Airman Shaw, rose and slipped into his breeches and puttees in the dark. By 4:00 a.m., Lawrence finished breakfast at his quarters. He had come here several years before, hoping to find peace in anonymity and simple work, following his disgust with duplicitous British post-war policies in the Near East, where he had fought to liberate the Arabs. Joking with other airmen as he passed, Lawrence made his way to his 1000cc Brough-Superior. Nick-named “Boa” by Lawrence, the twin-cylinder Brough was the super-motorcycle of its day. It produced 53 horsepower and was capable of entirely unsafe top speeds; Lawrence would own eight of the beasts in his life. It was the best-engineered, most powerful, fastest motorcycle then available. Riding Boa, Lawrence—one of the most famous, yet intensely private men in Britain—was further freed from his former, complicated life. Boa eagerly carried him that day from town to town on the narrow dirt roads, bisecting the calm English countryside. He stopped for sausage and ham early-on, and later for hot chocolate to warm him. Her roared through the old cathedral city of Lincoln, past Retford, north to Nottingham, and farther: freedom, power, speed, escape.

“A miracle that all this docile strength

waits behind one tiny lever

for the pleasure of my hand,” [1]

Ten years later, in May 1935, Lawrence would die from injuries in an accident on an identical motorcycle, after he swerved and lost control to avoid two young boys on bicycles. Free at last.

Equating speed with freedom, and understanding that it was the Brough’s technical specifications which allowed him the liberty he craved, Lawrence would no doubt have melded immediately with any group of American motorcyclists, yesterday or today. Speaking the language of their shared culture, they could swap comments and compare insights on displacements, speed, mechanical peculiarities, accessories, and the best riding routes. Lawrence and many like him—particularly Americans—would certainly agree: there is just something about a motorcycle.

Sharing Cultures From Across the Pond

Americans and the British have in fact shared motorcycle culture, from its creation. Indian and Harley-Davidson both sold motorcycles in Great Britain from the very early 1900s, and a more benign ‘British Invasion’—this time not with armed “Red Coats”—was the importation of high-performance British motorcycles to the United States, beginning in earnest in the 1940s. In the pivotal American biker movie The Wild One (1953), all the members of Johnny’s (Marlon Brando) gang are in fact riding British motorcycles. (Curiously, most members of rival Chino’s (Lee Marvin) gang are on American-built Harley-Davidsons.)[2] Currently, in the United States, British motorcycles still historically constitute the principal non-Harley-Davidson product to be accepted as a ‘real’ motorcycle, among Harley purists.

In recent decades in North America—as in England—the fascination with motorcycles and motorcycling culture has increased. Much of the interest is directed towards the more sensational ‘outlaw’ culture, with popular reality television shows like “American Chopper” and dramas like “Sons of Anarchy” offered in response to Americans’ insatiable desire for stories about anti-authoritarian biker lifestyles. [3] Old motorcycles have also become objects of curiosity and value to Americans; “American Pickers” focuses on the discovery of ‘Americana’—particularly relishing old motorcycles—and suggests the idea, whether true or not, that the old motorcycle in our barn or rusting in the yard invariably has value.[4] The present-day viewer is informed that an old product like this usually holds great monetary worth and historical meaning, once the right people take notice of it. Like some other discarded utilitarian objects in the United States, motorcycles seem to follow a similar and predictable trajectory: starting out as a wanted and useful item, they eventually spend a requisite purgatory in disuse, and then one day are pulled from the refuse pile as a desirable antique and ‘collectable.’

The Greatest Symbol of American Culture?

The motorcycle, similar mechanically and yet differing from the automobile in ways both subtle and obvious, has come to stand as a symbol for certain qualities we consider ‘American.’ More so than the universally accepted and ubiquitous automobile, the motorcycle is a polarizing object; it elicits strong positive or negative opinions from most people. It is dangerous—as we remember the perpetual limp a grandfather carried with him his whole life, our grandmother forever warning us about the infernal devices. It represents freedom—able to carry us on that rite-of-passage graduation trip to the coast; or simply away from our hum-drum present circumstances, be they physical or emotional. When we were young, it propelled us over the hot earth under its own power to our delight, without the dismal labor of pedaling a bicycle or walking. It is rebellion from the safe and predictable norm; it can exude a working class, anti-establishment, don’t-screw-with-me street toughness. Or, it can be imagined as the affordable, egalitarian mode of transportation for the people—perhaps falsely, as motorcycles originated as toys for the wealthy, and remain so, if we consider current prices and the motorcycle’s overall limited practicality. But, Screw practicality! its proponents maintain. A full tank of gas, cleaned and shining like a weapon, it stands ready to speed the American of David Potter’s accelerated, competitive, always-moving characterization forward. Forward to the gates of that mythic, larger-than-life American frontier, described by Frederick Jackson Turner and Roderick Nash, and painted in lush colors by the great Western landscape artists. [5][6][7] Emanating anti-authority attitude, the motorcycle promises to remove us from our present circumstances; to make us stand out, to yell we are somebody, and not just another cubicle-dweller. We move on “out to [our] big two-wheeler” when we are “tired of [our] own voice,” as Bob Seeger sang, our motorcycle serving as escape vehicle from staid suburban conformity.[8] We are Marlon Brando, terrorizing the sheepish townspeople; Peter Fonda on his chopper, leaving the squares behind; Steve McQueen spraying gravel in Nazi faces.[9] If only we possess it. Speed device, instrument of self-destruction, declaration of individuality, giver of freedom, antidote to mind-numbing conformity: the motorcycle.

A brief history of motorcycling in America

“Some people will tell you that slow is good—and it may be, on some days.

But I am here to tell you that fast is better.

I’ve always believed this, in spite of the trouble it’s caused me.

Being shot out of a cannon will always be better than being squeezed out of a tube.

That is why God made fast motorcycles, Bubba. . . .”[10]

American motorcycle history, spanning just over a century, warrants a brief re-telling here. The motorcycle (in early times called a moto-cycle; and then motor-cycle) appeared concurrently with and developed in parallel to the automobile. Both were dependent upon the invention of self-contained engines, which initially included steam, electric, and internal combustion types. For the first 100 years, at least, internal combustion won. Germans Gottleib Daimler and William Maybach are traditionally credited with having produced the first motorcycle in 1885.[11] The Daimler/Maybach machine was powered by petroleum-fueled internal combustion engine, fitted with two large wheels, and had two small “outrigger” wheels to keep the machine erect while turning. It should be seen to be an original transportation invention, in that it did not owe its form to either conventional four- or two-wheeled vehicles—meaning it was not just a bicycle with an engine attached. Interest in bicycling did influence motorcycle design several years later, however, when inventors such as Swedish-American immigrant Carl Hedstrom—soon to cofound the Indian Motocycle Company—attached engines to bicycle-type frames.  Hedstrom’s motorized hybrid was used to pace bicycle racers and to provide wind ‘drafting’ for racers as they went around the track.[12] The first production motorcycle frames, while similar geometrically to those of bicycles, were noticeably heavier and larger than the earlier bicycle derived devices. This was to cope with the additional weights and stresses of the engine, fuel tank, oil tank, drive mechanism, and other added features. Motorcycle design improvements accelerated world-wide through the 1910s and 1920, with the machines becoming both more capable and more practical. Further technical evolution of the motorcycle in the United States, specifically, is discussed in the following chapter.

Hedstrom’s motorized hybrid was used to pace bicycle racers and to provide wind ‘drafting’ for racers as they went around the track.[12] The first production motorcycle frames, while similar geometrically to those of bicycles, were noticeably heavier and larger than the earlier bicycle derived devices. This was to cope with the additional weights and stresses of the engine, fuel tank, oil tank, drive mechanism, and other added features. Motorcycle design improvements accelerated world-wide through the 1910s and 1920, with the machines becoming both more capable and more practical. Further technical evolution of the motorcycle in the United States, specifically, is discussed in the following chapter.

Early American motorcyclists sought out one another in order to share technical knowledge and to jointly deal with the challenges of abysmal roads and the initial scarcity of good maps and fuel.[13] They also immediately began to compete with one another, initially choosing to view the motorcycle as a performance device, above practical concerns. Early motorcyclists in period photographs are often pictured in riding groups. Clubs formed throughout the United States, and some clubs purchased land and built clubhouses on the acreage, facilitating picnicking and frequent racing events. We see that from its beginnings, motorcycling developed very much as a social activity. As the 1900s became the 1910s and the 1920s, motorcycle clubs and motorcycle competition became more and more entrenched in American life, as motorcycle manufacturers stressed the social, sporting, and healthy outdoors potential of the motorcycle. As competition flourished, motorcycle companies did manufacture special racing machines for their teams and for serious racers, but in fact every motorcycle could do double-duty as a competition mount; most early competitors rode to and from the races on the same machines they competed on. In the United States, the presence of race tracks near many towns—built originally for horseracing—facilitated motorcycle racing. “Flat-track” or “dirt-track” racing became a popular attraction at these ½ mile and mile fairground ovals across the United States. Motorcycle races also fit neatly into the “velodromes,”—banked wooden tracks originally designed for bicycle racing. Velodrome motorcycle racing become an exciting and wildly popular attraction, though it proved extremely dangerous to both spectators and riders.

Given both the additional physicality necessary to ride a motorcycle, and the ever present exposure to the elements—not to mention its lessoned cargo space when employed as a hauling device—the motorcycle has always served more as a recreational device, compared to the more stable and larger car or truck. While motorcycles and modified versions with two rear wheels and a storage container did see commercial service as delivery vehicles, they could generally not rival an inexpensive four-wheeler’s utility. Contrary to the popular idea that the early motorcycle was primarily cheap transportation for Americans, it actually began as something of an amusement for wealthier owners—as can be seen in the Indian company’s advertising description of its product as “A Gentleman’s Mount” in the next chapter. Once used motorcycles entered the marketplace and could be purchased for lower prices, less-than-wealthy Americans also became riders and were able to experience the wonder of the new motorized conveyances.

The very first semi-practical American motorcycles had appeared in 1902. Oscar Hedstrom and George Hendee’s single-cylinder Indian of that year was functional, but the machine’s design made it unsuitable for everyday drivers. It was complex, mechanically finicky, and relatively expensive. In 1909 an Indian motorcycle retailed for between $175 and $325 on the east coast; a significant price at the time, considering the annual salary of the average worker was not much over $400. Until used and smaller motorcycles became available in later years, buying such a machine for economy was counterintuitive. As Henry Ford’s mass-production techniques filtered into the motorcycle industry in the 1920s, motorcycle prices did come down, but buying a new motorcycle mostly remained a decision for a mechanically competent young male of fairly established means—though some young women did ride.[14] As the years passed, lower-price, more reliable, and lighter-weight motorcycles made riding more accessible to a wider spectrum of American buyers.

Motorcycle Development – 1930’s and 1940’s

Motorcycle development in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s, as opposed to England and Europe, tended towards the production of large, heavy, and fast machines. This can be interpreted as a reaction to the potentially long distances traveled and the then good availability of fuel.[15] Another reason for this tendency was the fact that American motorcycle buyers tended to be ‘enthusiast’ buyers, and enthusiasts valued performance over economy. The “v-twin” engine design—the two-cylinder fore-and-aft arrangement favored by Harley-Davidson, Indian, Excelsior, and other manufacturers in the United States—became the standard engine configuration offered on the larger machines. The v-twin thus ingrained itself as the preferred “American” type of motorcycle engine, though it did not originate in the United States: Gottlieb Daimler of Germany built one as early as 1889, and they were popular in England and in other European countries. Through the World War II years—and after the Great Depression years had winnowed out most other producers—these large-capacity Harley-Davidsons and Indians were the kings of American roads. Owners of the big native-built machines were jolted, however, when English-made Triumphs, BSAs, Royal Enfields, and other quicker and lighter ‘vertical-twin’ engine motorcycles—with the two cylinders arranged side by side, in parallel—began arriving in the United States after the war. Given a choice, many Americans—including many of the returning servicemen—took to the lighter and better-performing British bikes. These dynamic post-World War II years also saw the birth of a new feature on the American landscape: anti-social motorcycle ‘gangs.’

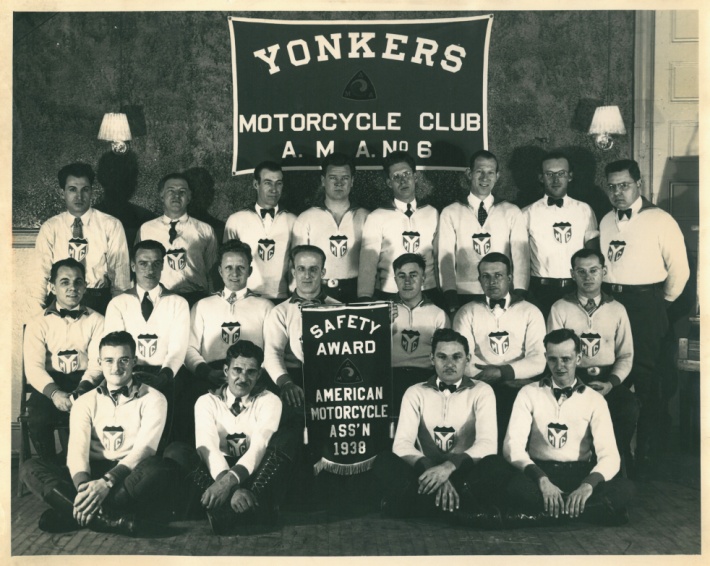

Prior to World War II, motorcycle riding was largely a hobby, enjoyed by knowledgeable adherents. It carried little of the ‘rebel’ connotation now attached to motorcycling, although the sport was obviously more risky than many other contemporary recreational activities. Riders were often members of community-based clubs, and might have worn matching uniforms—or at least a tie, in the male’s case—when riding (as is seen in Figure 4). The popular image of riding in the early pre-war years might in fact be compared to that of mountain-biking, kayaking, and rock climbing today: it was a somewhat daring and still evolving ‘adventure sport,’ but without any significant negative stigma attached. During these early decades of the 1900s, Americans were in awe of new technologies, and enjoyed the spectacle of machines moving quickly. Airplane demonstrations and automobile races were popular, and motorcycling held the same allure of speed, noise, and power. The American Motorcycle Association (AMA) formed in 1924 and had become the recognized sanctioning body for motorcycle racing in America. Local clubs often applied for charters from the AMA, again evident in Figure 4, which allowed them to conduct racing events and connect with riders around the country. With the AMA’s help, other forms of competition followed velodrome and flat-track, including road-racing (more accurately described at racing on a closed-circuit paved track), scrambles racing (held on a closed-circuit course over natural terrain with a minimum requirement for a mild jump and several other features), cross-country and desert racing (racing from point to point with the competitor determining the exact route), and the American invention of hill-climbing (attempting to reach the top of a massive hill from a standing stop, involving chain-wrapped rear wheels for traction and “catchers,” men hanging down the hill from ropes to assist in restraining men and motorcycles when they fell). In later years trials competition (negotiating natural obstacles without the rider’s feet touching the ground), enduro (long cross-country courses, usually through wooded areas east of the Mississippi, on which riders seek to maintain a set pace), and motocross (which too the place of scrambles racing in the United States) also became regular events in the United States. Motocross had its roots in post-World War II Europe, particularly in Great Britain, France, Sweden, and Belgium; and had matured into a popular spectator sport by the early 1950s. The sport was introduced to American riders in the mid-1960s. Taking root quickly, motocross became the premier motorcycle sport with American participants and spectators by the 1970s, and forms much of the background setting for this dissertation.

With the end of World War II and the return home of millions of soldiers, a significant new actor in American motorcycling culture appeared. This character was the “outlaw” motorcycle rider. Anti-social or “socially-deviant”—that is, resisting societal authority and deviating from social norms—motorcycle gangs can be traced to the years prior to World War II in a few cases. [16] [17] However, it was with the onslaught of returning young servicemen—some not finding or not wanting jobs, some negatively affected by the war, and others simply bored in their new peacetime environment and still craving the adrenaline that the war provided—that quickly led to this largely American metamorphosis from the law-abiding motorcycle clubs to the anti-social gangs. The most significant contribution to American motorcycle gang and outlaw[18] culture was the ride of the Boozefighters—a gang with pre-war lineage but a decidedly post-war identity—to the sleepy California town of Hollister, over the July 4th weekend of 1947. Upon the groups arrival, ex-Army Air Corps gunner and leader William Forkner and his gang of succeeded in disrupting the scheduled AMA racing and spoiling the town’s 4th of July festivities, getting drunk, and landing in jail. Their deeds, while highly publicized, stopped well short of “terrorizing” the town—and Forkner’s miscreants may have counted themselves lucky to have not been on the wrong side of Hollister’s citizens’ own sense of justice, had they taken their behavior much farther.[19] But, taken up by the media and sensationalized, Forkner’s Hollister nuisance became the ‘Hollister riot,’ beginning a process of re-defining the motorcyclist to America—and the motorcyclist to himself. It is important to consider the two major protagonists in the Hollister story. Conspicuously present at Hollister and standing with the town’s citizenry were the AMA-sanctioned motorcycle racers, and opposing them were Forkner’s non-AMA, ‘outlaw biker’ motorcycle riders. Thus, the recognized initial conflict and bell weather event of outlaw motorcycle culture was that of motorcycle outlaws contesting with mainstream motorcycle racers.

This admittedly rare physical clash of cultures—within motorcycling—remains today a fascinating social marker, bringing attention to the potential differences between sport riders and some in the ‘biker’ community. Several years after the Hollister event, the event was again re-invented and further sensationalized in the 1953 movie The Wild One.[20] Marlon Brando’s character, Johnny, clad in leather, epitomized a slightly less threatening rebel attitude: “What are you rebelling against, Johnny?” the local girl asks; “Whadya got?” Johnny answers. The movie was a hit—though shocking enough in its time to be actually banned in Great Britain for 12 years after its release[21]—and provided archetypes for road-riding fashion and for the socially rebellious motorcycle rider, persisting to this day.[22]

[1] T.E. Lawrence, The Mint (London: Jonathan Cape, 1955), 242.

[2] The Wild One, dir. by Laszlo Benedek (1953; Columbia TriStar, 1998 dvd).

[3] “American Chopper” ran 2008-2010. “Sons of Anarchy” aired first in 2008 and is still in production.

[4] “American Pickers” aired first in 2010 and is still in production.

[5] David Potter, People of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American Character (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 46-68 . Potter described an American as always moving forward, competitive, and seeking advancement to a higher level.

[6] Frederick Jackson Turner, “Significance of the Frontier in American History” (lecture, American Historical Association, World Columbian Expo, Chicago, IL, July 12, 1893). Turner wrote of the importance of the notion of a frontier to the American psyche, feeling that the wilderness/frontier was the “formative influence” on the American national character.

[7] Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967). Nash echoed Turner, and further affirmed that American consciousness required a wilderness in which to place both its past and its future.

[8] Bob Seeger, “Roll Me Away” on The Distance, Capital/EMI MW0000195656.

[9] Referring to Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953), Peter Fonda in Easy Rider (1969), and Steve McQueen in The Great Escape (1963).

[10] Hunter S. Thompson, “Song of the Sausage Creature,” in The Art of the Motorcycle, ed. Mathew Drutt, 44-7 (New York:The Guggenheim Museum, 1998).

[11] Steven E. Alford and Suzanne Ferriss, Motorcycle (London: Reaktion Books, 2007), 19-20.

[12] Hedstrom, along with bicycle racer and businessman George Hendee, formed the Indian Motocycle Company in 1901.

[13] Harry V. Sucher, The Iron Redskin (Sparkford, Somerset: Haynes Publishing Group, 1990), 47.

[14] For a photojournalistic review of early American female riders, see: Christine Sommers Simmons, The American Motorcycle Girls: A Photographic History of Early Woman Motorcyclists (Stillwater, MN: Parker House Publishing, 2009).

[15] Sucher, The Iron Redskin, passim.

[16] Danny Lyon, The Bikeriders (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2003), 6-7. Lyon noted that oldest mid-western outlaw motorcycle gang began prior to World War II, in the late 1930s. Most other gangs are post-war formulations. And, while motorcycle gangs are largely an American occurrence, other locations—notably in Britain, with the legendary “Mods” and “Rockers” movements—also saw organic gang formations.

[17]Alford and Ferriss, Motorcycle, 114-116. Alford and Ferriss use the term “socially-deviant” to define the outlaw biker—the motorcyclist who resisted societal authority and deviated from social norms. Also see Alford and Ferriss for further discussion of social deviance, biker identity, and gang origination and culture.

[18] ‘Outlaw’ is a term used to describe a wide range of meaning in motorcycle culture. Depending upon its context, it may refer to entirely benign, non-AMA-sanctioned races, or to truly anti-social, criminal behavior.

[19] Tom Reynolds, Wild Ride: How Outlaw Motorcycle Culture Conquered America (New York: TV Books, 2000), 31-58.

[20] The Wild One was first shown in movie theaters on December 30, 1953. Since it scarcely appeared in 1953, many sources report the movie as having been released in 1954.

[21] Mike Seate, Two Wheels on Two Reels: A History of Biker Movies (North Conway, NH: Whitehorse Press, 2000), 9.

[22] Alford and Ferriss, Motorcycle, 89-93.