No products in the cart.

American Journalism, Dirt Bike Magazine, Motorcycle Culture, Rick Sieman

Friends Talking: DIRT BIKE Magazine and Conversational Journalism in the 1970s

Abstract: In the very early 1970s, at the height of the worldwide motorcycle boom, an ad salesman named Rick Sieman envisioned a journal which would enable honest information to be exchanged between enthusiasts. He imagined this journal as the equivalent of “friends . . . talking,” and leveraged his modest resources to found DIRT BIKE Magazine, a monthly publication which profoundly united and affected a generation of young American males. Four decades since DIRT BIKE appeared and then faded from its original format, it continues to exhibit a fascinating impression on its now-fifty-something former readers.

DIRT BIKE is here examined by the author by means of reception studies; interviews with Sieman, a later editor, and former readers; and a contextual analysis of early 1970s American motorcycling culture.

Friends Talking: DIRT BIKE Magazine and Conversational Journalism in the 1970s

On a hot day in 1968, in the backstreets of Redondo Beach, California, a man in his late-20s walks into an uninviting motorcycle shop. His latest career iteration is as salesman for a biker magazine. Motorcycles are the new “in” thing, and southern California has assumed the role as incubator, as California always seems to do, for this new fad. The man likes motorcycles; he believes he can make this work. The other older, experienced salesmen for the magazine have had no success whatsoever in breaking into this market. The man takes a very different approach to the job. Rather than approaching the business owner—a custom “chopper” products maker—in a suit and with an overly pleasant demeanor, the man will meet the owner on the owner’s terms. He will speak his language. As he describes his technique:

“Well . . . I got a Harley-Davidson shirt, and I would ride up on a motorcycle, park the motorcycle in front, walk in, and say ‘Hey!’

‘Yeah—whadya want?’

I say, ‘Hey, how’d you like to make some money—some real money? You make sissy bars, right?’

‘Yeah—best f*****g sissy bars in the business.’

‘Well, how’d you like to have people send you money, and when you get around to it, you send them the sissy bar?’

And the guy’d say, ‘Is that legal?’

And I’d say, ‘Yeah—it’s called Mail Order.’

‘No shit—how’s that work?’

‘Well, you put an ad in the magazine, and the people see this and say they’ve gotta have that sissy bar. And they send you money for that sissy bar, and when you’re damn good and ready . . . damn good and ready . . . you weld that bar up, you chrome it, and you mail it to them. Simple as that. You even charge them for the mail!’

The guy would say, ‘No shit . . . you can really do that and not get busted?’

‘Yeah.’ And the guy would sign a year contract.” (Sieman 1995, 2012)

The young man, Rick Sieman, did indeed excel in sales, and very quickly become a star at the offices of Daisy/Hi-Torque Publications in Encino, California. Sieman continued to sell advertising for the big street bike magazines, at the same time becaming personally more involved in a different motorcycle phenomena: the emerging off-road motorcycling scene. Southern California—“SoCal,” as it came to be abbreviated—once again, was the worldwide locus of this explosion of interest in riding motorcycles “in the dirt.” Sieman saw that there were no magazines really in tune with the rapidly expanding off-road movement, and that segment of the popular motorcycle media that did devote space and time to off-road riding tended to be street riders or road-racers, trying their best (and usually failing) to appear cognizant and interested. These magazines and their staid writers did little to build a bond between themselves or amongst the emerging dirt riding community, and could be embarrassingly out-of-touch.

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw an explosion of interest in small and off-road motorcycle sales. The principal factors contributing to this were: the availability of lightweight, well-made, and inexpensive Japanese “trail bikes;” the meteoric American passion for “moto-cross,” (a new form of racing, similar to the older “scrambles” racing, involving competition on a closed course over natural terrain); the availability of high-quality, two-stroke [-engine]-powered European (and soon Japanese) competition motorcycles; and the unchallenged access to vast areas on which to ride. For most young persons, the idea of getting a powered ride—be it on horseback or powered bicycle, as an alternative to walking or riding a bicycle—had long been a dream, and they and other segments of American society purchased motorcycles in record numbers. By the very late 1970s interest had faded and world-wide sales dropped precipitously, with many small manufacturers failing (Russell 2005).

Sieman noted the lack of honest, informed journalism as he plied his sales trade on the SoCal backstreets for Big Bike and other Hi-Torque/Daisy specialist magazines. Daydreaming while he carried on the perfunctory talk of Choppers, Hogs, and Shovelheads, he imagined a truthful and straightforward alternative to the product-testing habits of the then-leading motorcycle publications. It would be a forum, a conversation across the growing community of riders. In Sieman’s own experience after races, home-bound riders would always stop at the same restaurants and bistros along the California highways and talk. This talk was honest and held nothing back from those asking the questions. What was the right way to change a tire or tune an engine? How did a certain new motorcycle model actually perform? Which products were really good, and which were not? These men behaved and spoke much differently than the educated, professional writers at Cycle and Cycle World; they were “buddies . . . friends talking.”(Sieman 1995) They were utterly honest and believable—as well as entertaining. Why couldn’t there be a magazine, Sieman thought, which spoke the same way these men did—friends talking?

Parlaying his currency as a leading salesman to give weight to his dream of starting a magazine, Sieman relentlessly prodded and pushed Daisy/Hi-Torque about his dream magazine. Finally the publisher relented; but Sieman would have one shot and that was it. Sieman’s rough paper mock-up became the [slightly less rough] first actual DIRT BIKE newsstand copy in June of 1971. In a business where new magazines never sold well in early production, DIRT BIKE’s very first issue sold phenomenally well, achieving 70% sales of the total newsstand distribution. This was an incredible sales rate for any magazine at the time, much less a first issue. The publisher was amazed; Sieman’s idea proved right, and DIRT BIKE was rushed into monthly publication.

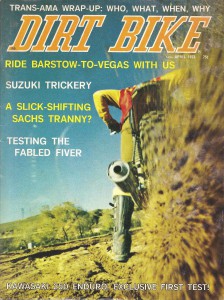

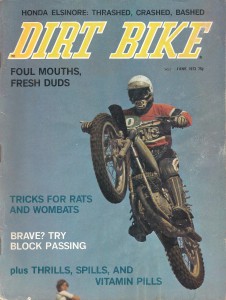

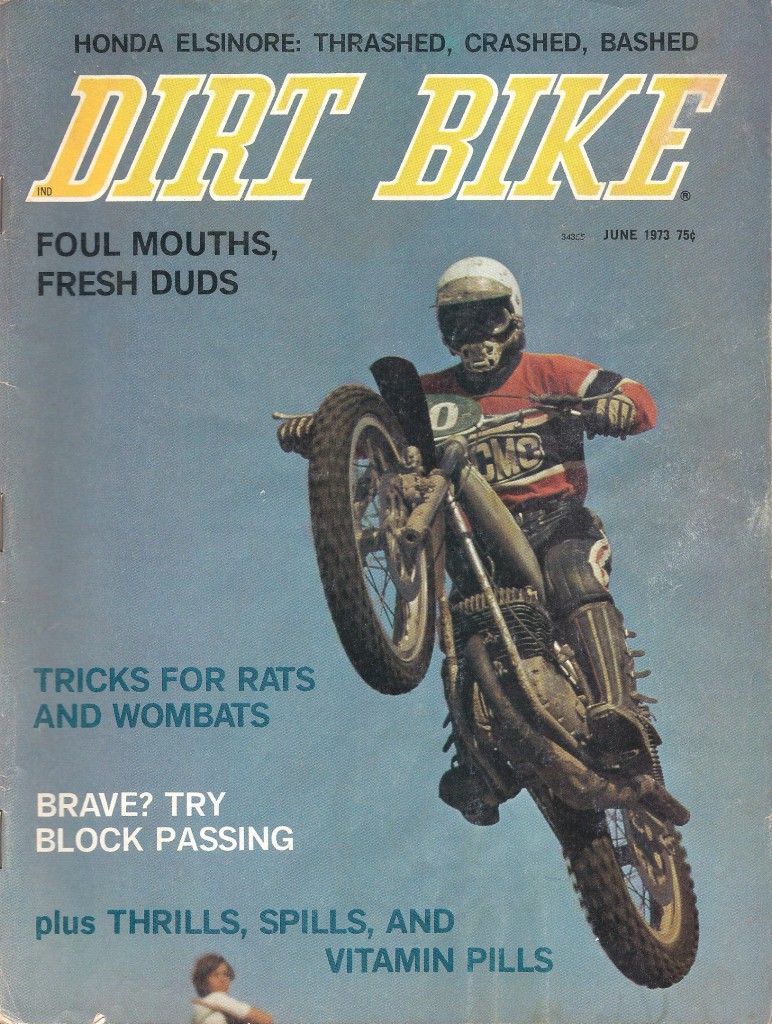

Two editions of the mature Sieman-edited magazine in 1973, a year before Sieman’s departure.

The magazine in its early editions comprised less than 100 pages and was light on advertising, but the newsstand (and soon, subscription) sales kept it afloat. Along with the straightforward and humorously-crafted product evaluations, Sieman, associate editor Pete Szylagyi and the rest of the tiny staff contributed regular columns and outright comical entries. Throughout each issue coursed a common stream of self-deprecation, honesty and humor that reinforced Sieman’s primary directive of “friends talking.” DIRT BIKE in its early years attracted (and nourished) a strong following, and its pronouncements on motorcycles and products were held up as tantamount to Biblical truth within the off-road community. Sieman himself became known to and revered by thousands of American young men as simply “Super Hunky,” a nickname given Sieman for both his Pennsylvania/Eastern European background (“Hunky”)[i] and for his strength (having been an Olympic power-lifter and, later, an arm-wrestler not to be taken lightly). Super Hunky also became a recognized personage among young males in the junior high school halls of early 1970s America; unusual for a publication not yet targeted especially to a young audience. DIRT BIKE’s readers felt themselves privy to special membership in this new fraternity of off-road motorcycle enthusiasts, bound by both their interest in motorcycles and the seemingly-personal writing, which appeared directed precisely at them. These readers took up the pronouncements and verbal inventions of the writers—made-up terms such as “high-zoot,” “WFO,” “trick,” “foo-foo,” “mung-and-drool,” and “G.Y.D.B.T.,” to name a few—and used them in conversation with like friends-in-the-know.[ii] The existence of this shared, private language intensified the sense of community. The magazine further created something of a communal forum, as the readers/members communicated among themselves on local levels with this new language, spurred on by the writing, even if they themselves were not normally writers.

The magazine in its early editions comprised less than 100 pages and was light on advertising, but the newsstand (and soon, subscription) sales kept it afloat. Along with the straightforward and humorously-crafted product evaluations, Sieman, associate editor Pete Szylagyi and the rest of the tiny staff contributed regular columns and outright comical entries. Throughout each issue coursed a common stream of self-deprecation, honesty and humor that reinforced Sieman’s primary directive of “friends talking.” DIRT BIKE in its early years attracted (and nourished) a strong following, and its pronouncements on motorcycles and products were held up as tantamount to Biblical truth within the off-road community. Sieman himself became known to and revered by thousands of American young men as simply “Super Hunky,” a nickname given Sieman for both his Pennsylvania/Eastern European background (“Hunky”)[i] and for his strength (having been an Olympic power-lifter and, later, an arm-wrestler not to be taken lightly). Super Hunky also became a recognized personage among young males in the junior high school halls of early 1970s America; unusual for a publication not yet targeted especially to a young audience. DIRT BIKE’s readers felt themselves privy to special membership in this new fraternity of off-road motorcycle enthusiasts, bound by both their interest in motorcycles and the seemingly-personal writing, which appeared directed precisely at them. These readers took up the pronouncements and verbal inventions of the writers—made-up terms such as “high-zoot,” “WFO,” “trick,” “foo-foo,” “mung-and-drool,” and “G.Y.D.B.T.,” to name a few—and used them in conversation with like friends-in-the-know.[ii] The existence of this shared, private language intensified the sense of community. The magazine further created something of a communal forum, as the readers/members communicated among themselves on local levels with this new language, spurred on by the writing, even if they themselves were not normally writers.

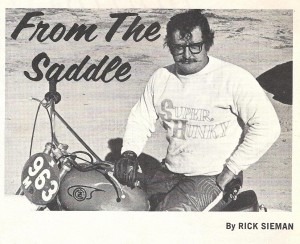

Rick Sieman as portrayed in his “From the Saddle” column in DIRT BIKE, and as captured by the author, photographing former motocross stars on the start line at the AMA’s Vintage Motorcycle Days in Ohio, circa 2008. One bit of fan trivia centered around Sieman, an unapologetic fan of German Maico motorcycles, being pictured on a competing Czechoslovakian CZ motorcycle in the “From the Saddle” photograph.

Feeling his editorial control on the magazine was constantly being threatened by management, Sieman left DIRT BIKE in frustration in late 1974 for work at other magazines. With his departure the publication immediately began changing, incrementally—certainly due in part to the shock to readers of Sieman’s patriarchal absence. The magazine continued initially with its existing staff, and for a while retained much of its editorial honesty and humor. Yet, by the late 1970s and following the changes made by a variety of different editors, the magazine had become a shade of its former self. By 1980, DIRT BIKE was “just another motorcycle magazine,” in the minds of most readers.

In terms of a print media product, what exactly was DIRT BIKE? Folklore and communications theorist Richard Bauman describes two principal varieties of media. One modality is the vernacular; a “communicative modality” characterized by informal practices, immediate and grounded communicative relations, and horizons of distribution that are spatially-bounded (Bauman 2008). The other is the cosmopolitan, characterized by being “rationalized, standardized, mediated, and wide-reaching.” Bauman describes the two as “opposing vectors in a larger communicative field.” Given these two choices, DIRT BIKE certainly does not meet the cosmopolitan definition. Further considering the Sieman’s intent, the text itself, and the magazine’s reception among readers, DIRT BIKE is certainly a vernacular media product, using Bauman’s criteria. It is the creation of a reasonably common and “of-the-people” sensibility and invokes a participatory call to its readers—even while being funded and distributed by a corporate entity. Like other rebellious American periodicals dating back to the 1800s (an example being the “Free Love” publications studied by Jesse F. Battan, advocating radical changes to sexual mores in the mid-1800s), DIRT BIKE attempted an intimate, “face-to-face” conversation between writers and readers (Battan 2004). DIRT BIKE’s editors and readers, like Battan’s contrary newspaper editors and readers, saw themselves very much as a voice-in-the-wilderness counterpoint to the existing establishment media. Similarly, the entrenched motorcycling media did not meet the expectations or share the values of many 1970s riders, and thus the countercultural voice of DIRT BIKE—as The Word, Nichols’ Monthly, and the Social Revolutionist did a century before—found an audience. All these publications, DIRT BIKE included, catered to and encouraged a “community of [the] like-minded,” as Battan describes the readers in his own research (Battan 2004).

Although DIRT BIKE might be considered “old media” in the definition of modern media scholars, recent studies in “new media”—principally digital media—may help us to further identify the magazine, and to understand the magazine’s role and affects on readers. Robert Glenn Howard analyzes more recent digital vernacular media in his “The Vernacular Web of Participatory Media.” Howard, in a slight twist on Bauman, breaks down digital media culture again into two primary varieties: the vernacular and the institutional. Similar to Bauman’s description of the cosmopolitan, Howard progresses to define the institutional as that which conveys “original intent;” that is, originated by a corporate, structured entity, with a formal purpose and intent (Howard 2008). Howard’s descriptions of digital media may be useful in helping to ascertain DIRT BIKE’s [granted, decades-older] place in media. Howard goes on to note that, besides just the pure strains of the vernacular and the institutional, a third composite variety of media inevitably surfaces: the hybrid. The hybrid, combining aspects of both vernacular and institutional, very much locates DIRT BIKE’s position: dependent upon established, corporate sponsorship, production, and distribution; but simultaneously countering that same corporate value system in many ways.

Noting also Howard’s recognition of “subaltern” and “common” vernaculars, we can further place DIRT BIKE. Both these descriptions relate to agencies that are alternatives to dominant power structures. In Howard’s explanation, the common vernacular functions against marginal oppression in a “limited” way. The subaltern vernacular is a response from groups whose agency is “severely limited or denied by social structures (my italics).” The question of whether the DIRT BIKE readership’s voice was marginally or severely limited by the existing 1970s corporate media is open to discussion; we can say, however, that the voice was indeed limited (as we have seen and will further observe).

Rick Sieman, in his interview with me, very emphatically referred to his intent for DIRT BIKE as one of “conversational journalism.” This description, despite its apparently clear, positive, and practical implications, is, surprisingly, not a common expression in journalism. One of the very few uses of this phraseology dates back of Margaret Fuller, a mid-1800s American literature critic. As Leslie Eckel notes in her analysis of the writer, Fuller “practiced a form of journalism she described as ‘conversational’.”(Eckel 2007) Fuller conceived of her writing as an exchange of ideas, even as she wrote and others read, in static continuance. Fuller’s concept—similar to Sieman’s—was that even though the writer and readers were engaged in what was essentially a one-way communication, there still existed some degree of “conversation.” The exchange occurs in something of a “feedback loop,” wherein the writer puts forth ideas in the text, readers consume and applied meaning to the text, and the writer continues or modifies future texts as a result of approval (sales) and reader input. Applying this theory to DIRT BIKE, writers went beyond being writers to also function as readers (or at least consumers) of other texts to some extent: analyzing input from racing results, assessing manufacturers claims and product performance, and absorbing ideas from industry insiders and the culture at large. They then analyzed this data, applied their intended meaning, and passed on this information to the readers in future editions. Margaret Fuller intended to push her readers “to transform society on a grand scale, through imaginative cooperation.”(Eckel 2007) Rick Sieman and the writers at DIRT BIKE likely harbored no illusions about changing society at large, but nonetheless consciously strove for better ways in which their emerging society could communicate and conduct their lives.

What do former DIRT BIKE readers recall about the magazine and its meaning? Readers of the publication in its early years, at this writing in their early-to-mid fifties, recall its impact on their lives differently. The magazine clearly inspired divergent meanings among various readers. Some readers dealt with the magazine only in passing, while others were deeply affected by it. One respondent, a retired Army officer, noted that DIRT BIKE “even had some influence on [his] view of life.” He further admitted that even now he uses “Dirt Bikisms” (referring to the word creations and abbreviations) in regular speech. He believes that the magazine provides insights into the political and cultural climate of the 1970s, and agreed that there was simply no other magazine akin to DIRT BIKE in the early days (before, he notes, it became “just another magazine”).

Another reader, a former professional motocross racer and now an employee at a state agency, had the same fond memories of the magazine, but remembered “disappointment and confusion” at the time with some of the magazine’s apparent attitudes [towards other motor sports]. He noted the “friends talking” aspect of the magazine and conceded that other magazines tried the approach, but remained “distant.” This reader consciously moved away from DIRT BIKE to Motocross Action in the early 1970s, seeking a more pragmatic review of machinery, with less humor and more technical analysis. This serves to verify [late-1970s DIRT BIKE editor] Gunnar Lindstrom’s goals in his move from a lesser reliance on humor to a greater emphasis on fact-based engineering analysis and reporting (Lindstrom 2012).

Rick Sieman himself—or, Super Hunky, as he was commonly know—was venerated by readers in the early years, and continues to be a recognized personality within the off-road motorcycling community at large. One respondent (a present-day motorcycle journalist) referred to Sieman as “a god” and generally as someone who could be completely trusted. Another respondent, a retired executive, stated “There was only one Super Hunky!” and [he] “was the magazine.” Sieman’s print of authorship on DIRT BIKE was utterly tangible, and most readers felt that the magazine was never of the same quality after Sieman’s departure.

Not all readers agreed with the idea of “community” in DIRT BIKE. One respondent, currently a technology executive, stated emphatically that he couldn’t “recall ever having any great feeling of ‘community’ by reading the mag,” and suggested that this might be due to a “west coast” flavor overpowering his “east coast” world view. Others former readers likewise did not necessarily respond to any sense of community between them and either writers or other readers.

In attempting to explain this divergence of meaning among DIRT BIKE readers, we might turn to modern reception theory as a tool. There are a number of ideas at our disposal which could assist in describing the magazine and the readers’ reactions. In earlier times, we may have taken a New Criticism stance and labeled the response of readers to DIRT BIKE as being clearly text-activated. After all, we have seen that the writers overtly “coded” information for readers (an example being the “G.Y.D.B.T.”). The writers certainly expected the readers to understand the codes, or to take the time to investigate and learn them (both actions serving the writers’ purposes: to amuse readers and to “let them in on a secret”). Given this and other examples of intent on the part of the writers, it is difficult to quickly dismiss a classical writer-originated/text-activated response description, in favor of more radical reception theories.

Janet Staiger makes a strong case for reader-activated and context-activated theories of reception, as she discards text-activated theory (Staiger 1992). Considering reader-activated theory, we might imagine the individual readers, at home with their copy of DIRT BIKE, allowing their own personalities to inform their reading of the text, and imposing their own world-view on the data, product reviews, jokes and stories. In this view, both similarity and variety in meaning would be created at the point of reading, based upon the individual reader (and the filters that the reader applied in the reading process).

Context-activated theory suggests that the context of the reading experience (not the writers) informs meaning. Readers play a part, but less than that allowed by reader-activated theory. The response may have incorporated nuances in textual meaning (consider again DIRT BIKE’s play with altered and made-up expressions), the [still-developing] mores of early off-road motorcycling culture in 1970s America, and also the socio-economic circumstances of the readers.

Whether the readers—especially in light of the younger male audience the magazine cultivated—possessed the necessary “tools” suggested as necessary for the processing of the text in any of these ways is a consideration. Whether they were, in fact, “ideal,” “coherent,” or “competent,” in Staiger’s definition, is debatable. That a 13-year-old could correctly interpret (and not “misread”) the writer’s intention—particularly when considering a text-activated approach—is certainly not a given statement of fact.

Janice Radway observed that romance-readers in her 1980s reception studies shared a “wish to be cared for, loved, and validated.”(Radway 1984) Might (especially) the young readers of DIRT BIKE have felt the same way? I submit that, besides whatever factual and practical content it had, the magazine provided validation for these young teens, passing through the emotional netherworld of Junior High School, between childhood and adulthood, in a 1970s America which had changed considerably from the world their parents knew.

Philip Goldstein and James L. Machor, in gazing over the field of American reception studies twenty years after both Staiger and Radway, ask us to refrain from any overly-limiting choice of one theory over all others, and to consider that many theories of reader reception may have something to offer (Goldstein and Machor, 2008). Certainly all the theories presented above appear applicable to an understanding of DIRT BIKE, in one or anther way.

The memory of humor in the pages of DIRT BIKE was eternally fresh among respondents. While drafting this paper, at precisely this section, I took time to speak with a technician who was repairing our home fireplace. Knowing that this man was an off-road rider, I asked him for any recollections he might have of the magazine. Almost immediately, this man laughed as he recalled and paraphrased some of Rick Sieman’s comedic lines from 40 years ago. He responded without a moment’s hesitation: “. . . and the drill bit seemed to pick up speed, as it went through the fender I was drilling, and into the meaty part of my thigh . . .” Given the time separation between the writing and reading of this text (and the reader having likely not referenced it during the entire interim of four decades) and the recall of the text, this recollection seems incredible. And, it suggests something remarkable in the otherwise unassuming and everyday writing style of the DIRT BIKE editors.

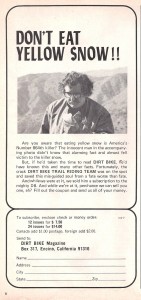

Most readers not only recalled the humor of the magazine, but also still used old DIRT BIKE phrases in everyday life—likely to the consternation of hearers not familiar with the referenced content. Gunnar Lindstrom (writer and editor at the magazine from 1975-1977), when asked to be interviewed for this study, likewise (and again, almost immediately) responded with a reference to “the plush, well-lit, high-zoot offices” of DIRT BIKE, referencing another humorous phrase from four decades past. Just as the editors of the magazine used verbal humor, they also incorporated visual comedic devices into the text. Subscription ads, racing coverage and product tests were often laced with visual as well as textual humor. One particularly-memorable combination of both devices came in the April, 1973 issue. In this issue the magazine parodied itself, conducting a tongue-in-cheek “test” of their old El Camino work truck, named the “Great Yellow Dirt Bike Truck,” and commonly referred to as the “G.Y.D.B.T.”[iii] Written and generally conducted just as the magazine would test other machinery or products, the essay was completed with photos and complex, technical-looking yet nonsensical charts.

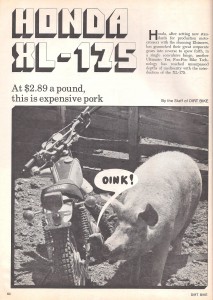

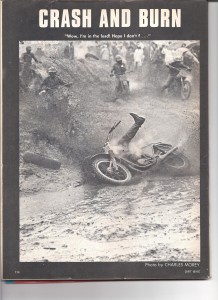

Three examples of humorous visual content in DIRT BIKE. On the left, Sieman’s image is used in a reference to mistakenly eating “yellow snow” (containing urine). In the middle, a Honda motorcycle is parodied as a “pig” owing to its low power, high weight, and mediocre performance. On the right is the monthly last-page “Crash and Burn” feature, generally showing some sort of dramatic-but-hopefully-harmless-and-laughable crash.

As Deborah Tannen points out in her analysis of conversational styles, our choice of certain words can facilitate a “closeness” between speakers (Tannen 2005). We can extend this analogy to one connecting writers and readers. Some words are inappropriate in particular situations, and also between speakers and listeners/readers not yet on the intimate terms which allow the use of this phraseology, as mandated by social norms. And, at the proper times, these and other terms—slang, contractions, puns, and informal expressions—actually work to establish closeness between speaker and listener. The writers of DIRT BIKE did much to remove barriers between themselves and the readers by their early incorporation of slang and improvised language. The repeated use of invented language like “high-zoot” and “G.Y.D.B.T.” created and reinforced a very tangible closeness and a bonding between the writers and readers. For the reader, knowing the meaning of G.Y.D.B.T. and other “Dirt Bikisms” created an intimate connection that outsiders—not knowledgeable of the code—could not be a part of. Tannen also notes that communicators use speaking “style” to create images of themselves, meant to craft a specific, desired perception by others. These styles and techniques vary with gender, class, ethnicity and other factors, and assist in establishing identity among speakers and bonds between speakers (and, between writers and readers). This use of language to create such a connection is an especially notable facet to DIRT BIKE’s success at gaining an immediate and faithful readership. This communicative device on the part of the writers, more than any other, may be the factor that made DIRT BIKE “different from all the other magazines.

Who were DIRT BIKE’s readers? Age-wise, respondent data suggests a group between twelve and twenty-four years old; or, precisely the age young men discover motorcycles. It is likely that older motorcyclists at the time were set in their ways and tended to stay with whatever publications they had been reading. While Sieman and the other editors do not appear to have specifically targeted mid-teenagers, it is this demographic that would have come into young adulthood at the time and begun to search out its own texts for pleasure consumption.

The readers were mostly white and vastly male. While one respondent to my requests for feedback was African-American, and one respondent was part Cherokee Indian, these two instances should not suggest any large degree of multi-ethnicity among either DIRT BIKE readers or off-road motorcyclists. As the African-American respondent explained, northern (and generally more affluent) blacks were still largely urban in the 1970s, and the idea of purchasing an off-road or racing motorcycle—one that could not even be used for legal transportation—simply did not enter into their ideas of sport or practicality. The white males which made up the majority of the off-road culture were from suburban or rural homes, nearer the riding areas that made off-road motorcycle riding practical.

In terms of education, the levels of the respondents varied between that of high school graduate (all) and post-graduate (several). Other socio-economic characterizations included that of a career in a skilled trade (conducive to the upkeep of a motorcycle), being a small-business owner (especially a motorcycle dealer), and military service. Although motorcyclists in general are often categorized as being “risk-taking,” “countercultural,” or “anti-authority,” one should be cautious in applying such labels—especially if based upon cultural myths or outward appearance. To offer an analogy, just as UC Berkeley student radicals discovered in 1965 at a Get Out of Vietnam rally, to which they invited the Hell’s Angels, the fact that a motorcycle rider has long hair and doesn’t follow certain rules, doesn’t mean he (or she) is left-leaning or “countercultural” (The Rolling Stones would make the same mistake at Altamont in 1969).[iv] Likewise, long-haired motorcycle racers of the 1970s were generally anything but left-leaning. As often either skilled workers themselves or the sons of skilled workers, and from families who both had adequate financial resources to help afford an off-road motorcycle and were willing to allow their children to race it, these young men tended to be more conservative and right-leaning. While I would characterize the younger riders as [naturally] apolitical in their outlooks, older riders (and respondents to my inquiry) could be characterized as politically centrist or right-of-center.

Danny Lyons’ photographic biography of motorcycle gang members and racers in the 1960s American mid-west illustrates differences and similarities between the two groups that remained accurate through the 1970s, and on into the new millennium (Lyons 2003). Lyons’ pictures and text noted two very different types of men. The gang members, portrayed by Cal and Sonny, were anti-authoritarian and doomed to a life of not fitting in with conventional society, while at the same time being members of communities (their clubs). The racers (which most closely equate to the off-road riders and racers reading DIRT BIKE, portrayed by Johnny Goodpaster and Frank Jenner), though functioning within established society, were also communal beings and also felt some degree of alienation from the dominant societal power (the media, the conservative establishment, and the police). Both groups complained of misunderstanding and periodic harassment by conventional society. Yet neither group was counter-cultural. The racers, in particular, were very clearly working-class and reasonably conservative; they were business owners and workers who saw themselves as very conventional and “regular” Americans. These men saw value in physical work that produced a tangible result—a car repaired, plumbing installed, a ditch dug—and were emotionally content in this cycle of work and product.[v] Riding and racing—working hard to excel—was a predictable extension of this lifestyle.

While recognizing their attraction to what many would consider a needlessly dangerous activity (racing), the racers mentally minimized the risk as something little more statistically dangerous than driving cars, hunting, flying airplanes, or any of the other “risky” activities that other Americans engaged in, but which were not assigned negative connotations by the dominant culture (Lyons 2003).

As John Wood further notes in his “Hell’s Angels and the Illusion of the Counterculture,” committed motorcyclists of the period were not simply “motorized hippies,” and the New Left’s early adoption of them as co-believers and protectors was vastly misplaced (Wood 2003). While 1950s popular culture enjoyed portraying motorcyclists as “outlaw heroes” and individualists, many—especially motorcyclists belonging to gangs or clubs—were anything but individualists. Off-road motorcyclists (although to a lesser degree than their more notorious “outlaw” distant cousins) often found meaning in being part of their particular club and sport. This desire for group or communal belonging was and remains a valid characterization of all motorcyclists.

We can go further in describing the off-road motorcyclist, this time from an American Studies perspective. As these young men of the 1970s were often engaged in competitive events, David Potter’s description of the mid-century American as always moving forward, driven by a competitive spirit, and seeking success, seems especially accurate (Potter 1954). These men, like earlier Americans, sought out challenge. To bring in a major early-1970s event, more often than not these were the young men who went to Vietnam—like it or not—and not those who protested against the war and remained safely at home. The off-road riders’ values were generally not those of any countercultural persuasion. In Will Kaufman’s description of 1970s America as a “vigorously-contested battlefield,” (between the left and the right) the young men who rode and raced off-road were more than likely [Kaufman’s] young “neo-cons[ervatives],” and not the liberals seeking societal change (Kaufman 2009). Finally, we note anthropologist Barbara Joans’ interview with a rider named Lynn, in which Lynn states of the Harley riders she has met, “I used to think that bikers were really radical people. When I found out how conservative they were, it surprised me.” (Joans 2001)

More recently, motorcycle culture scholar Steven Alford characterized the motorcycle itself as an object that “. . . brings people together,” and that riding “. . . unites you with other riders (my italics).”[vi] Clearly, motorcycling in practice differs greatly from the iconographic loner rider of American myth. Motorcyclists, whether street-riding club members or off-road riders, overwhelmingly tend to consider themselves part of some larger community, and a part of some greater effort.

The young motorcyclists reading DIRT BIKE and searching for community were acting entirely as could be expected.

The years 1971 through 1974 were the “glory days” of DIRT BIKE. When Rick Sieman left in anger and frustration for another editorship in late 1974, the world of motorcycling itself was beginning to change as well. Coincidentally, two important events buffeted motorcycling in 1974. First, this was the year that “long travel suspension” was first introduced onto production motorcycles. While at first glance a simple suspension change would not appear to affect an industry that much, the change from conventional to long-travel suspension for the motorcycle industry was tantamount to the change from conventional piston engines to jet engines in the aviation industry. The advance put significant strain on all manufacturers to improve their products—at significant cost—and many smaller makers were unable to comply with consumer demand in time to remain viable. Secondly, by 1974, world motorcycle sales had reached their zenith. This tapering-off in sales was the result of inflation, the 1973 global energy crisis, and unfavorable currency devaluations in America and elsewhere (Youngblood 2000). As the later 1970s approached, sales would drop off more significantly, and many smaller manufacturers would leave the marketplace. Iconic, once-dominant makers such as Maico, CZ, Husqvarna, Puch, Monark, Triumph/BSA and others fell back as the Japanese “Big Four”—Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki—replaced them in market dominance.

Thus, Sieman’s departure occurred simultaneously with the crest of a wave of other changes. In Sieman’s absence, a number of other editors tried taking the helm at DIRT BIKE, but something was missing—and a bit more of it with every passing month. While immediately-subsequent editor Chet Heyberger continued Sieman’s style, any media product trying to emulate a missing person’s vision, without some degree of change, is likely to only go downhill. Later editors verged more and more from the original format, and, perhaps, it was necessary for the times. Gunnar Lindstrom, a staffer in 1975 and editor in 1976 through 1977, when asked about the former [Sieman] style, responded as follows:

(Interviewer): DIRT BIKE’s founder, Rick Sieman, describes this concept he had for DIRT BIKE as “friends talking,” or, something else he used, “conversational journalism.” Did you continue that . . .?

(Lindstrom): No, I didn’t. Because I wasn’t able to . . . I tried to be more of an engineer, and for accuracy. A lot of people liked articles that were more funny . . . but I think that after Sieman left, that kind of journalism faded a bit, in favor of accuracy. And I think the advertisers required it; demanded it in many ways. Of course, it could backfire, too (Lindstrom 2012).

While a still a strong magazine, DIRT BIKE in the later 1970s varied significantly from that of the early years. Whatever it gained in professionalism, it lost in both its ability to entertain and to communally link enthusiasts. By 1978 and 1979, DIRT BIKE had completed the transition from Sieman’s original vision, and become simply “another motorcycle magazine.”

DIRT BIKE was a unique media creation. While the product of the conventional institutional media, it immediately moved to a vernacular stance. It served to promote a dynamic new sport, to bind this community together, and to ingrain readers with memories and world-views that would remain with them decades later. When we accept that DIRT BIKE was, strictly speaking, no more than an enthusiast magazine, written by young, inexperienced enthusiast writers, learning as they went, this is remarkable.

End Notes

[i] “Hunky”: Old mid-eastern American slang term for eastern-European (such as Polish, Czech, and Hungarian) immigrants.

[ii] Meanings of made-up words: “high-zoot”: impressive, elegant; “WFO”: wide f*****g open (as in the throttle being wide-open; probably not an original DIRT BIKE creation); “trick”: custom, improved; “foo-foo”: low-grade, ridiculous; “mung and drool”: leaking oil, grease; “G.Y.D.B.T.”: Great Yellow Dirt Bike Truck (see also page 6 and associated footnote)

[iii] DIRT BIKE’s practice of abbreviating names by using initials was a common humorous staple in the early years. The method resembles military practice (more Army than Naval service), which tended to utilize segments of syllables rather than only first letters of words). For example, several military veterans who read the magazine in early years, later invented the expression “MiRV” (Motorcycle Recovery Vehicle) for their trucks or vans, a reference to both DIRT BIKE and their military backgrounds.

[iv] As Hunter S. Thompson relates in Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga, members of the Hell’s Angels attacked Berkeley anti-war protestors, to the apparent amazement of the assembled students and protestors, in October 1966. In 1969, at the famous Altamont Rolling Stones concert, Hell’s Angels employed as a security contingent murdered one man and beat up many others. Ultimately, extreme motorcycle gangs are far better described as reactionary than countercultural, as John Wood suggests (Wood 2003).

[v] For a timely and perceptive discussion of the perceived value of and changing attitudes towards skilled labor in American society (and its tie-in to motorcycling), see Mathew B. Crawford, Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work (London: Penguin Press, 2009).

[vi] As quoted in Richard Hutch’s “Speed Masters Throttle Up: Space, Time and the Sacred Journeys of Recreational Motorcyclists,” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, July 2007. See also Steven Alford, “Why Motorcycle Studies?” in the same on-line journal, under archived articles.

Works Cited

Battan, Jesse F. “‘You Cannot Fix the Scarlet Letter On My Breast!’: Women Reading, Writing, and Reshaping the Sexual Culture of Victorian America.” The Journal of Social History, (Spring, 2004), 601-624.

Bauman, Richard. “The Philology of the Vernacular.” Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 45, No. 1, (2008), 29-36.

Coffey, Mary K, and Packer, Jeremy S. “The Art of Motorcycle (Image) Maintenance.” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, (July, 2007). http://ijms.nova.edu/July2007/IJMS_Artcl.CoffeyPacker.html. Accessed 5 November, 2012.

Crawford, Mathew B. Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work. London: Penguin Press, 2009.

Eckel, Leslie. “Margaret Fuller’s Conversational Journalism: New York, London, Rome” Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, Vol. 63, No. 2, (Summer 2007), 27-50.

Goldstein, Philip and Machor, James L. New Directions in American Reception Study. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Howard, Robert Glenn. “The Vernacular Web of Participatory Media” Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 25, No. 5, (December 2008), 490-513.

Hutch, Richard. “Speed Masters Throttle Up: Space, Time and the Sacred Journeys of Recreational Motorcyclists” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, (July, 2007). http://ijms.nova.edu/July2007/IJMS_Artcl.Hutch.html. Accessed 5 November 2012.

Joans, Barbara. Bike Lust: Harleys, Women, & American Society. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Kaufman, Will. American Culture in the 1970s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

Lindstrom, Gunnar, interview with the author, November 6, 2012.

Lyons, Danny. The Bikeriders. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2003.

Potter, David. People of Plenty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954.

Pratt, Terry. Grand Prix Motocross: The 1972 World Championship Season. Cycle News, 2007.

Radway, Janice. Reading the Romance. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press,1984.

Russell, David. “The Dirt Bike and American Off-road Motorcycle Culture in the 1970s.” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, (March, 2005).

Sieman, Rick. Monkey Butt. San Antonio Del Mar, Baja: Rick Sieman Racing, 1995.

Sieman, Rick, interview with the author, October 28, 2012.

Staiger, Janet. Interpreting Films: Studies in Historical Reception in American Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Tannen, Deborah. Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk among Friends. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Thompson, Hunter S. Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1967.

Wood, John. “Hell’s Angels and the Illusion of the Counterculture” The Journal of Popular Culture, 37, (2003), 336-351.

Youngblood, Ed. John Penton and the Off-Road Motorcycle Revolution. North Conway, NH: Whitehorse Press, 2000.

wow great article Dave! I’ll be looking forward to future articles 🙂

Thanks Michael! Just wrote another article on the Maico Motorcycle and Culture Part 2. Check it out and tell me what you think

Wow. a lot of detail in there, You obviously know your stuff. It’s amazing how much the world has changed since the 70’s. It’s always interesting to see how people can produce something successful just by looking at it from a different angle, and with a fresh pair of eyes. I look forward to your next article.

Mike–Rick’s still writing that ‘fresh’ stuff, too. He’s got a blog going. Oh–didn’t mention it in the essay, but he had the original paste-up of the first issue of DIRT BIKE–used to sell the idea–for sale some time back. Now wouldn’t THAT be an artifact!

It looks to me like a great example of what can happen if you keep something real from the offset and worry about the polish later (if at all). Sometimes the most brilliant of ideas come from the most simple things. Of course I’m referring to Sieman’s idea of taking the after race talk to print!

And just as a note of nostalgia… Look at those beasts that they are riding in those old pics!

Awesome article and also really thorough!

Brian–thanks. Yes, Rick Sieman sure was ‘real’ in every respect. I remember how much we kids looked forward to getting the monthly issues of DIRT BIKE–so we could quote everything as the “truth.”

Just looking at the image on the front of this magazine generates some nostalgia. Those were indeed the good old days. I still enjoy watching the x games motocross best trick. Wow, I didn’t know DIRT BIKE magazine reached 70 percent of the total newsstand sales. Impressive. This is what people like to read. Just the average day to day chat about motorcycles. Interesting that Sieman saw the value in this and was able to bring it to the masses. This type of reading was very refreshing amidst all the nonsensical business and political publications.

Thanks for bringing history alive and preserving the memory of this magazine. I really enjoyed reading this.

Glad it hit home! DIRT BIKE was certainly a unique publication, in its day. Now, I’d say, only RacerX Illustrated comes close.

Wow there is a history behind Dirt bike Magazine I never knew. Goes to show you have to get on the same level as other people to relate to them. It sounds like Dirt Bike magazine really had a dramatic effect on people’s lives and their views. I enjoyed reading!

Thanks, Shannon. Can’t speak for everyone, but for those dirt bike kids “of a certain age,” it really did!

Thanks Shannon glad you liked it!

Thanks for the comment, we’ll check this out. Glad you enjoy it

I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog.

Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself?

Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a nice blog

like this one today.

Have to give all the credit to my son, ChristianQ

This was such a cool site to visit as you’re absolutely right that motorcycles have captured the American psyche, especially that of young males.

DIRT BIKE magazine appeared to be ahead of its time, but then again many great ideas are. Much respect for Rick Sieman and for following his dream.

Alec, glad you enjoyed the essay. Rick Sieman is indeed a guy with the guts to follow his dreams and convictions. It would appear that you may have been one of those thousands of teenage boys like me who waited for DIRT BIKE to come every month! Dave

The author forgot the term Nasty-Go-Fasty. I so enjoyed the From The saddle articles. good memories.

It’s fun to look back at the articles by Rick Sieman that were written in the early 70’s. Rick would hit it right on with his humor, this was the time when a lot of the mx bikes didn’t like mud puddles, engines would lock up in mid air, there were two neutrals when shifting. Then you had gyt kits for your enduro to race mx. You may have a Wards Riverside, Bsa, or Husky all racing in the same heat. You wore a tee shirt, combat boots and a helmet, that was your safety equipment. The expansion chambers all swept down under the frame on the fast bikes, but didn’t last long. That was when a TM400 would blast down the straights in first just to be beaten by a 400 square barrel Maico in the rough stuff.

Gene, yes! Your recollection brings to mind my looking through Ken Smith’s beautiful book Hodaka the other day, and noticing the shots of the great Harry Taylor testing and racing in a t-shirt, along with just the equipment you describe. What were they (and we) thinking? Same with period photos of scrambling in the 1950s and 1960s. Was it something related to testosterone, or were we just crazy? Preparing a new post now on 1960s/1970s racer and shop owner Gig Hamilton, who recalls breaking bones in his foot, having the ‘medics’ in the ambulance crew wrap duct tape around the entire boot, and then getting right back out to race!

I remember buying the first issue of Dirt Bike Magazine. Just saw the first vintage issue sell for $120- in good cond. recently on EBAY. Wished I had kept all my issues of the magazine. I should have listened to Mr. Know It All. “YOU SHOULD OF KNOWN!”

I think I started getting DB about the 6th issue. Just got back from Vintage Motorcycle Days in Ohio, and Mr. Know it All (Vic Krause) was THERE!

Interesting article and fun read, thanks for posting. As the dirt bike obsessed teenager in the ’70s, I’m very familiar with Dirt Bike magazine and that era in general, though didn’t really discover it until 1975 or so. I did have a pile of earlier issues given to me by a friend at the time and pored over all them. Being a bit of the magazine fanatic, I read every publication available from 1975 until 1981 or so – Dirt Bike, Motocross Action, Modern Cycle, Popular Cycling, Cycle, Cycle World, Motorcyclist, Cycle News – am I forgetting any?

The ’70s dirt bike boom was about having fun, assessable to almost everyone. Bikes were fairly cheap to purchase and maintain, areas to ride plentiful. Dirt Bike magazine and others as well, reflected that and it felt like cool club you belonged to, complete with slang I still use today. It was great time to be involved with the sport at a formative time of your life, with many fun memories attached and still cross my mind 40+ yers later.

Oh yeah, like many – wish I saved those now vintage editions – I tossed ’em all in ’86 during a move…

Haha! Yes, Dan, and you’re not the only one to still use vintage DB language. My friends & I are hooked on the old “spacious, well-lit offices [of Dirt Bike]” phrase. Several years ago I was speaking with Gunnar Lindstrom. I used the phrase and–as I recall–even he immediately burst into laughter! (I don’t recall whether Gunnar was the editor yet, at the time of that writing.)

Rick Sieman is the greatest moto-scribe of all time. By the way, in the three pictures of the “Yellow Snow”, “Honda XL175”, and “Crash and Burn”, that’s me on the Maico in the mud hole with my left foot in the air. It was the Orlando round of the Florida Winter Series in 1973.