No products in the cart.

Dirt Bike Magazine, Trail Bikes

A Belated Defense of the “Trail Bike”…and the Search for the Perfect Trail

The term “trail bike” isn’t used much, these days. With the proliferation of highly-advanced dual-purpose (on- and off-road) motorcycles that really can do it all (mostly), both the design and the name of the original small displacement do-everything bikes have largely disappeared. But, these motorcycles still have their fans. Let’s take a look at the trail bike, in history and in use today.

First, what is a trail bike? For our purposes, I’ll suggest a definition as follows: a Japanese dual-purpose (that is, potentially street legal) motorcycle, particularly those made without long-travel suspension, and prior to about 1980. While there are exceptions to all the following characteristics, let me try to assemble a general description of what constituted a trail bike. These machines had engines from 90cc to 400cc; their designs incorporated off-road-derived frame geometry; they were made by Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki, Honda…and Hodaka; they had high fenders and mid-level or high, fairly quiet exhaust pipes; and they were equipped with the lights and gauges to allow them to be licensed for street use in most locales. They were, largely, America’s and Japan’s early idea of a dirt bike that could also be ridden on the road. These machines were also intended to be raced—if the owner wished to do so, and cared to modify the motorcycle accordingly.

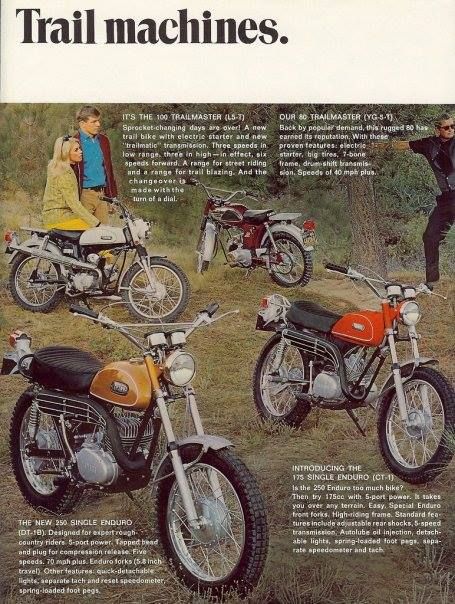

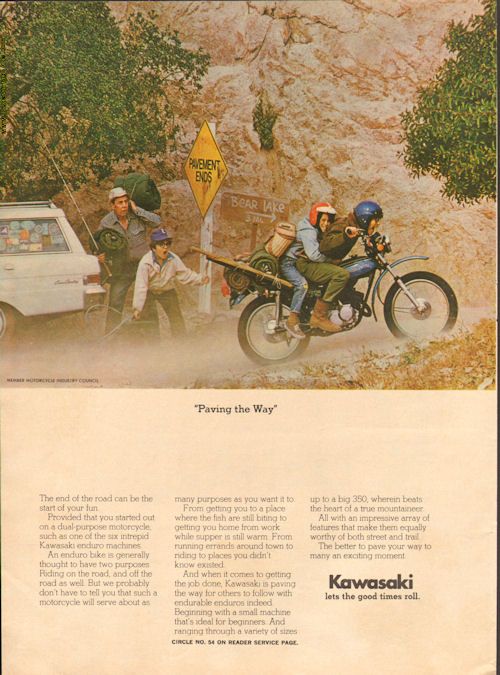

The term “trail bike” appears to have originated in the United States, as retailers and buyers sought to describe the new lightweight machines. Since the bikes differed from the usual motorcycle (a device meant to be ridden primarily on the street, as transportation) and were not, as sold, actual racing motorcycles, describing the machine as something to be ridden on the trail made sense. Early ads often pictured families riding recreationally, on mild trails. Trail bike thus entered motorsport language. Enduro, after the term for the popular off- and on-road competition event of the same name (derived from the word endurance) was also a used to describe this new class of motorcycle.

Yamaha and the DT-1

The archetypal Japanese trail bike is thought to be the 1968 Yamaha DT-1, a 250cc motorcycle designed with substantial input from two Americans working for Yamaha at the time: Jack Hoel and Dave Holeman.[1] Hoel, head of Research and Development for Yamaha International, believed from observing Holeman’s desert racing hobby that there was a need for a machine that could serve both as a competition mount, while also functioning as reliable and capable street machine. Their idea, in a way, was for the first specifically designed “dual purpose” motorcycle. At the time—about 1965-1966—small, light two-stroke motorcycles were beginning to replace the large, heavy four-stroke machines in off-road competition. Although there existed purist European competition mounts like Husqvarna, CZ, Maico, Bultaco, and others, there was little in the way of modestly-priced two-stroke motorcycles that could also perform reliably and without constant, extensive maintenance, on the road. The Spanish were experimenting with the idea (such as the Montesa Scorpion 250 in 1964 and various Bultacos), but their rather small market presence and distribution in the United States limited success. Japanese-made Hodaka—imported and influenced by the Pacific Basin Trading Company (PABATCO)— had also been making lightweight, high-quality motorcycles that were being used successfully off-road and in competition, and was enjoying some success as it sought to expand its American sales network. Motorcycle sales were accelerating world-wide, and the United States was by far the largest single market, eyed and approached by nearly every manufacturer. Yamaha International was interested in anything that would help US sales, and took Hoel’s and Holeman’s advice.

The white-tanked DT-1 was premiered at the Tokyo Motorcycle Show in October 1967, and available in the US and Australia a few months later, in 1968. The machine seemed to be exactly what Hoel and Holeman had envisioned, and demand immediately outstripped production. The DT-1 could be ridden quite nicely on the road to work, and—with the extraneous parts stripped off, and perhaps some Genuine Yamaha Tuning (GYT) hop-up parts added—raced or trail-ridden on the weekend. The DT-1 was a phenomenon in the motorcycling community, and every other manufacturer took notice. For their parts, the other Japanese factories rushed development of their own dual-purpose bikes, after Yamaha’s lead. Yamaha, likely amazed at the success of the DT-1, sprung into action and began designs for an extended DT-1-influenced family, in smaller and larger engine capacities.

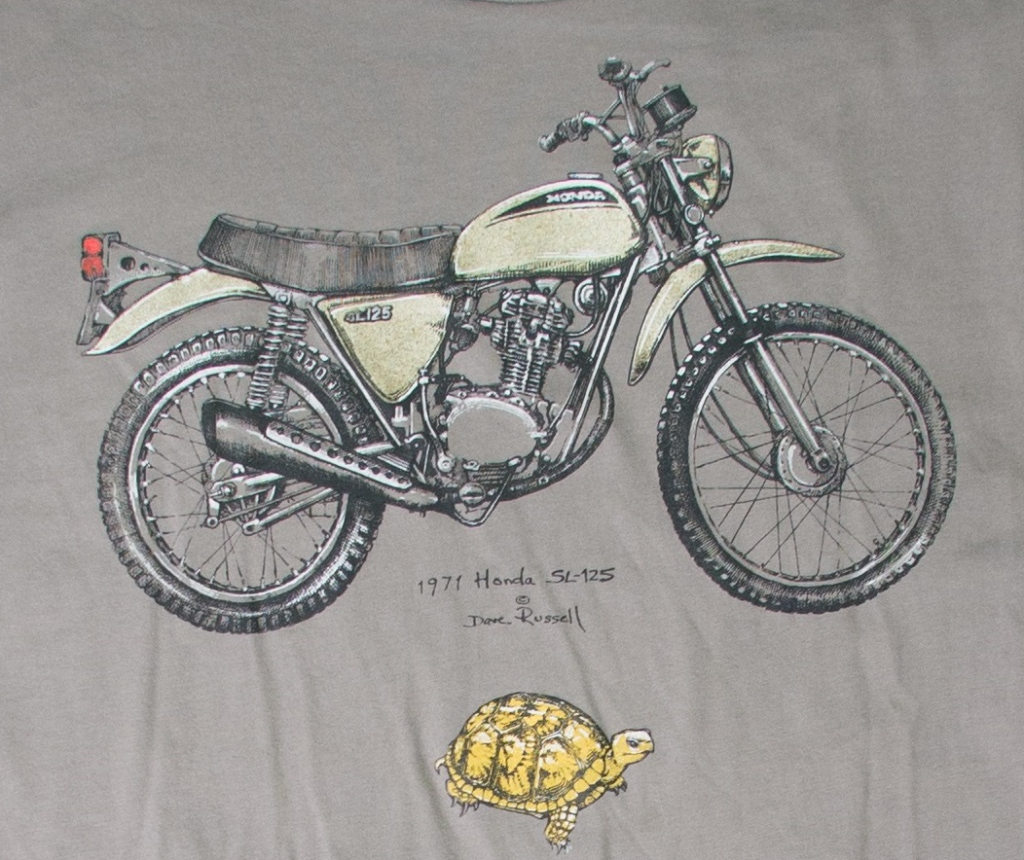

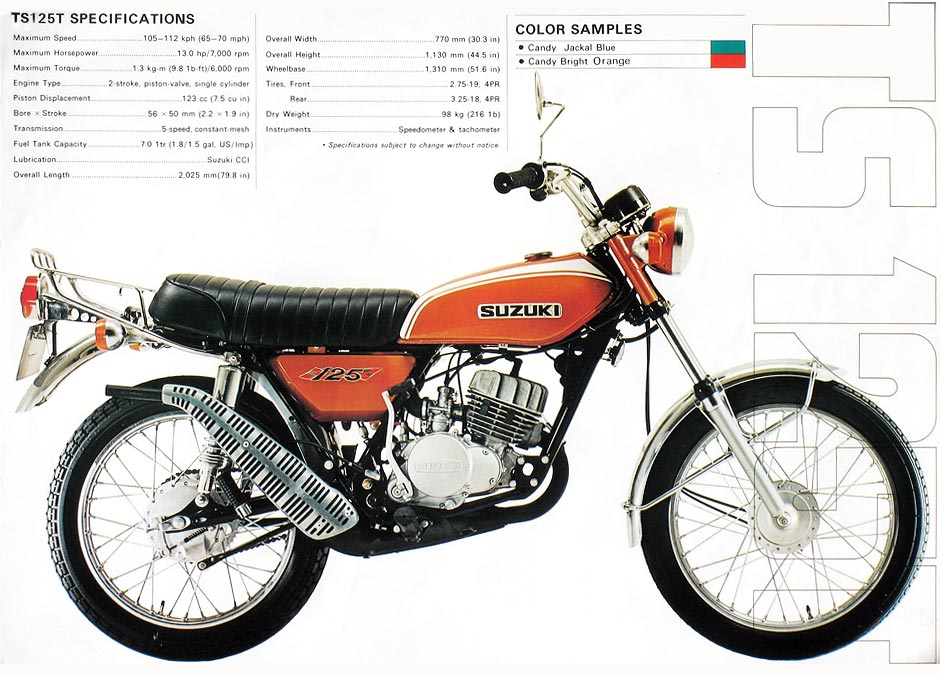

By 1970, the remaining three of the “big four” Japanese manufacturers had similar machines to the Yamaha enduro bikes. Suzuki began its TS line, Kawasaki its G- and F-series on/off road bikes, and Honda marketed its SL series—sticking with its four-stroke-only engine philosophy. Most of the machines came with “trials” tires, interpreted from the traditional trials competition tread designs, but with more plies. Some machines, like Kawasaki’s 100cc G4 “Trail Boss,” came with knobbies front and rear. The bikes nearly all subscribed to the evolving trail bike aesthetic: good ground clearance, high fenders (with Yamaha being the exception and holding fast to the low front fender for several more years), high exhaust pipes (here Honda was the exception), and an amazing (given the prevailing standard of British quality control, where oil drip pans sat under even new motorcycles in the dealerships) level of overall finish and reliability. With their attention to paint and chrome, as well as fit and overall finish, and with as many extra touches as could be added, the bikes were certainly ‘pretty.’ Naturally, these motorcycles were made to do several things adequately—vice one thing, perfectly—and had limitations. This was particularly true in the off-road environment, where their higher weight, marginal suspension components and tires, and compromise frame geometry could be lacking. Finally, as an alternative to buying and then modifying a stock trail bike for competition, the companies began offering full racing versions of the trail bikes. These included the Yamaha’s DT-1MX, the Suzuki TM series, and the early Kawasaki 100cc and 238cc production racers.

Dirt Bike Magazine and “Foo-foo bikes”

Dirt Bike Magazine, coming on the American motorcycle scene in 1971, was quick to capture the allegiance of off-road riders and competitors (and especially young riders) as an authority on all-things-dirt. Dirt Bike also lost no time in promoting itself as the one true and honest broker in the dirt-riding world.[2] Since the focal point of the off-road riding world was the off-road motorcycle, a major segment of Dirt Bike’s editorial content was that of ‘testing’ motorcycles. While the editors would have been much more at ease taking thoroughbred racing machines to the race track, they also realized that a great portion of their audience either did not race, couldn’t afford one of the exotic thoroughbred racers (and were using Japanese machinery), or were otherwise perfectly content with their Japanese dual-purpose trail bike. Thus, they had to include the Japanese bikes—which were, we can assume, what much of the motorcycle press readership actually rode.

How exactly to test such a multi-purpose device was actually a quandary for any motorcycle magazine. Should it be tested for what it was apparently designed to do—that is, be used on both the road and in the dirt? And, if so, how would you do that…write about its carrying capacity, evaluate its on-road handling en route to the grocery store, and then ride it around a race track? Clearly there was no easy answer. Dirt Bike declared that they would not attempt to test the Japanese trail bikes in the way the companies suggested they were supposed to be used, but rather in the way [Dirt Bike announced] they would be used: in the dirt. Competing with Dirt Bike for the young and off-road demographic were Dirt Cycle, Modern Cycle, Cycle Guide, and of course established magazines such as Motorcyclist and Cycle World.

And test them Dirt Bike and the other magazines did. The machines were sometimes analyzed separately, and sometimes in “shoot-outs,” with two or more like-capacity machines pitted against one another. While Dirt Bike certainly made fun of the various inadequacies of the Japanese bikes (from a pure off-road perspective), the editors sought to be fair in their assessments, and tried to address the bikes’ strengths, as well: basically their reliability, lower cost, and attention to finish. On the humorous side, Dirt Bike made a conspicuous point of noting all the superfluous items (such as lights, gauges, wiring, etc.) that a real off-road bike shouldn’t need, as well occasionally showing the machines and their riders stuck or in otherwise comical situations. Dirt Bike editors are also believed to have placed in common use the motorcycle version of the term “foo-foo,” meaning over-ornamented or lesser-performing. Much like a miniature poodle was a “foo-foo dog”—as compared to a rugged and functional German Shepherd, for example—a soft, overweight motorcycle was a “foo-foo bike.” Foo-foo has retained its meaning in motorcycling language to the present day.

Finally, Dirt Bike criticized the Japanese manufacturers for creating in buyers’ minds the idea of a “perfect trail,” on which there were no excessive bumps, hills, or other challenges. The perfect trail, the editors argued, did not exist. Actually, Hoel, Holeman, the many other creators of the original trail bikes, and even the manufacturers publicity departments, likely never had any such intent in mind. They were simply attempting to improve upon their current market reality of overly-heavy and less-reliable machinery, that needed to be both street-worthy and yet be viable in competition, as well as be affordable and practical to the common man. To that end, they succeeded.

The joy of trail bikes

But, were the foo-foo trail bikes really bad? I suppose one might contend that, at their intended function—that of being a foo-foo bike in the first place—they were actually very good. No other motorcycle at the time could be so versatile, while being so light, reliable, inexpensive, and comparatively good-handling. At their intended purpose of being, well…everything to everyone—though Dirt Bike would have contended such a niche did not exist—they were actually perfect. Today, they remain the cute little bikes that we rode, or we wanted. And, while many were used hard and discarded, there are many still available on the market, in either ready-to-ride condition or as restoration projects.

Buying

Obtaining a vintage trail bike is not difficult. The greater the population density, the more of the bikes will be available, locally. With the demise of most local papers and their “For Sale” sections, the best means of locating vintage motorcycles for sale is probably Craig’s List and eBay, in that order. I prefer Craig’s List over eBay these days, as Craig’s List seems to have absorbed a good chunk of the buying and selling of motorcycles which in former years would have been listed on eBay. (I would assume eBay commissions have much to do with this.) Besides not requiring buyers and sellers to deal with a third party, Craig’s List offerings are increasingly more numerous. For example, I live in the southeastern Pennsylvania area. Doing a search of motorcycles for sale made between 1970 and 1975 on Craig’s List sites in my “local” area (of about 200 miles in any direction) will normally result in a capture of over 400 motorcycles for sale.

Of course, word of mouth is great as well…and—unlike the Cobras and Vincents, supposedly still “in the barn”—there do seem to be some great finds for less-expensive motorcycles remaining, all around us. Recently, at a museum event, a vaguely familiar woman came up to my friend and I and asked “Do you know who’s interested in old motorcycles, here?” After simultaneously answering “I AM!” (and probably subconsciously pushing each other to the side, a bit!), the lady gave us a piece of paper on which were written her husband’s contact information and the description of a 1500-mile, nearly perfect 1971 Yamaha enduro. Several weeks later, the little 175cc CT-1 was in my garage, and I learned that the woman had been my high school English teacher.

Generally, one is better off spending more money up front and buying the best bike possible, as opposed to purchasing a rough bike for less, and restoring it later. Experience has shown most of us that we wind up having more money into a machine needing restoration, in the long run. Additionally, we can’t ride the bike for some time. To illustrate: My 1971 CT-1 was purchased for $1,500—not cheap, but not what the bike might bring to a very motivated collector, either. A typical CT-1 “roller,” missing parts, not with a title, having rusted rims and spokes, not running and in need of a major rebuild, might be had for $300—or less. However, after $350 in rims and spokes, an $800 engine rebuild, $500 in professional paint, another $400 in obtaining the bit and pieces which are missing, and, finally, $200 spent with a title service, suddenly our cheap bike isn’t so cheap. Perhaps more importantly, we’re now “underwater” as the expression goes, having spent more for the bike than it’s worth, should we need to sell it.

And, did I note the hundred or so hours of work?

Restoring

Still—and I’ve done it, myself—many of us are going to buy a rough bike in need of restoration and restore it. Obviously there’s a point at which the bike is too far gone to be economically viable. But, as King Solomon wrote, “with money, anything is possible.” One nice aspect of riding and maintaining a Japanese motorcycle is that there are so many of them! Since vast numbers of units were sold, there are many parts available. The sources include NOS, reproduction, and used, and their presences make restoration at least more practical. And, some long-time dealers may still have parts available. My experience, at least with Honda and Kawasaki, is that the Honda dealer has access to quite a few old parts and will happily back-order them from Big Honda…they’re just crazy-expensive. On the other hand, the Kawasaki parts man may simply look up at me and say “What? Naw…we don’t have anything that old.” (I confess to not having much experience with Yamaha and Suzuki, though Speed and Sport Yamaha is an example of a dealer which focuses very heavily on vintage Yamaha parts.)

Outside of the dealers, parts are available on eBay and through specialized vintage dealers—just begin your search on the internet, and sources will appear. I’ve personally bought from a few vintage Japanese suppliers in Taiwan, and been pleased with the product, even if the shipping was rather expensive. These businesses have a big presence on eBay, and are easily found. (Vintage Avenue is an example of such a supplier.)

As I’ve mentioned in other writings, don’t be afraid to do certain work yourself…while “knowing your limits (as Clint Eastwood might say)” and letting professionals do what you can’t, or shouldn’t. While the following list will vary with each individual’s bank account and mechanical abilities, here is my suggestion for best practices for Japanese motorcycle restoration:

Buy a workshop manual, first. The aftermarket ones are OK, but a factory manual is usually best and more detailed.

Take digital pictures of the motorcycle, before you take it apart, and as you take it apart, to make re-assembly easier. With digital cameras, this is so quick and cheap you have no excuse. Also, I recommend using masking tape to mark everything, indicating which way it goes on, what it connects to, etc. (You may think you can’t possibly forget in what order this or that piece goes on, or which of the two black female leads the single male connection plugs into…but you will forget!)

Unless you’re experienced, consider having a professional rebuild your engine—at least the bottom end. One misplaced washer can necessitate a second rebuild!

Don’t be afraid of sub-assemblies. YOU CAN rebuild forks, do top ends, and re-spoke a wheel, just to name a few tasks that we might find intimidating. And, other enthusiasts are usually eager to lend help.

Re-chroming is very expensive. You’re usually best off to find another used part in good condition, or even buy new (in the case of rims, for example).

Painting is not that hard, even if you’re limited to spray cans. Spray cans will actually give quite satisfactory results on frames, fenders, and small parts. Remember to prep well, sanding or sandblasting and then using a good primer, and also to use paint that is resistant to oil and gas (you can buy most basic colors as “engine paint” at your local auto parts store.) If you have access to a compressor and a professional body shop spray gun, professional two-part automotive paints will go on easier and will dry harder.

Fasteners will usually need to be replaced. Resist any temptation to use non-metric nuts and bolts you have around the shop. Most hardware stores today have excellent stocks of metric fasteners, and you will be able to find 95% of the items you need there. For specialized fasteners, check eBay or a dealer.

I tend to put a modern dual-sport tires on my old enduro bikes, which both look nice and give updated (and safer) performance—and which functions well on both street and in the dirt. Updated “trials” tires also look good, but the real thing (that is, for actual trials motorcycles) can be expensive and very thin-walled.

Have a good time! The restoration process may not be cheap, but it should be enjoyable. You’ll take great satisfaction in knowing that you were able to “bring back” the motorcycle.

A nicely restored–and rather rare–1972 Kawasaki F6 125. The Kawasaki line used mostly rotary-valve engines, and were predictably the quickest of the Big Four offerings. This motorcycle is wearing modern Kenda dual-sport tires, which are both inexpensive and aesthetically pleasing.

For additional information regarding motorcycle restoration, check out our 3 part series entitled “Motorcycle Personification, Modification and Performance Upgrades”.here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Riding (and registration)

Once you give your new beauty the First Kick and she hopefully roars to life, you can certainly ride around the fields, or in other off-road places. One of the nicer aspects of operating an old trail bike, however, is that they can be licensed for the road. I’ve enjoyed riding my old trail bikes around the local neighborhoods on nice evenings, and sometimes on longer, modestly paced 20- or 30-mile trips with friends. And, having an old trail bike street legal means you can ride it on the road, to the trails, as I sometimes do (being lazy and never eager to go through all the work of connecting the trailer, loading, and such.

In most states you can register your old trail bike as an antique vehicle. This is usually a distinct benefit, since antique status—at least in the states I’m familiar with—means 1) you aren’t required to have inspections, 2) your registration is permanent (i.e., no yearly registration charges), and, 3) insurance is usually cheap (more on that, later). If you’re going to register your new bike as an antique (or classic), specify this desire when you and the seller first sit down with the notary to transfer the title. By this I mean that there is no need to pay for a “regular” title, before you get your “antique” title—you’ll just be paying extra, needlessly. You should be able to transfer registration from the seller to yourself, and register it in your name as an antique or classic.

Of course, this process may become more complex if you buy the bike in rough shape, or don’t have a title from the seller. I mention the former situation because some states still may require pictures of the potential antique motorcycle, in good condition (to prevent against people registering their piles of junk, to save money). In my state of Pennsylvania, this is no longer the case, and photographs are not required. In the latter case—no title—you should contact one of the title companies who specialize in obtaining titles for old vehicles. (While I have yet to do this, I’m told it’s fairly painless and will usually cost about $200 to get a title for your machine. However, the clear title you do get will probably be from another state [often Vermont], so you’ll still have to go through the process of getting your permanent antique title and registration in your own state.)

One concern that I often hear, with regard to both antique registration and insurance, is “Yeah, but you can’t drive/ride during the night, and only so many days a year.” While insurance will specify that it’s assumed your antique is not a “daily driver,” and the states likely have similar language accompanying antique registration, this usually isn’t the problem people may imagine it is. For one, why would you want to drive your antique after dark much, anyway? And I, for one, do not plan on using my fleet of little trail bikes as everyday transportation to my job. So, I find that concern with limits on driving antiques is generally misplaced.

Antique motorcycle insurance

Good news: insuring antique vehicles is affordable. Another nice aspect of classic/antique insurance is that the companies seem to realize 1) you’re going to take good care of your antiques, and 2) if you have several of them, you can’t ride them all at one time. Thus the cost of coverage tends to decrease with subsequent vehicles. For example, I have my old car insured for $54/year (with the normal deductables, medical coverage, etc.). Then my first antique motorcycle is $68 (higher than the car, due to bodily injury insurance costs), while my second and third antique motorcycles are only $15/year. So, for about $150 a year, I am fully insured for one classic car and three classic motorcycles.

A note on antique motorcycle value

While a desire to accumulate wealth is not be the best reason to buy an old trail bike or two, you may be surprised, in the long run, with the wisdom of your purchase. As a rule, buyers of vintage motor vehicles tend to buy what they wanted, or had, when they were young. There is, therefore, an enormous field of fifty-to-sixty-something former Japanese trail bike owners, who are now potential buyers…and tend to have disposable income. In my own vintage motorcycle circle, I’ve noted men who have restored and raced vintage motocross machines for the past 20 years, who are now increasingly interested in the trail bikes they also owned as teenagers. The trail bikes bring a host of advantages, including being less maintenance intensive (both in money and time) and the fact that an older rider is less likely to hurt himself riding slowly on a trail bike, than racing a powerful competition bike around a motocross course.

Observation of selling prices on eBay and other venues suggests that very good to excellent condition trail bikes are currently worth as much or more than comparable motocross machines. With the baby boomers of the early-seventies riding generation still a decade from age 70, I believe that values will continue to gradually rise for the next ten years. There are few other purchases that one might say the same about.

Pull out that trail bike and head for the Tastee Freez!

Click HERE to view our SL-125 t-shirt in our shopping gallery. We’d love your support! I hope this essay has been enjoyable. We always welcome your suggestions and comments!

[1] Colin MacKellar, Yamaha Dirtbikes (London, England: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 1986), 14.

[2] This was particularly so after the magazine wrote such scathing reviews of motorcycles by some major manufacturers, that the manufacturers would no longer either provide test machines nor buy advertising in Dirt Bike. The magazine lost no time in proclaiming their role as the one media outlet that would never alter the truth in return for advertising dollars.

Raced an SL 125 for the local shop, just hold it wide open forever! Man those little engines were tough. Used to set the timing by loosening the breaker point plate, then holding it wide open and turning the plate until the engine screamed. Ah the good old day.

Yes, your 71CL 350 Honda for sale? And if so, how much?