No products in the cart.

Dirt Bike Magazine, motorcycle oral history, Rick Sieman

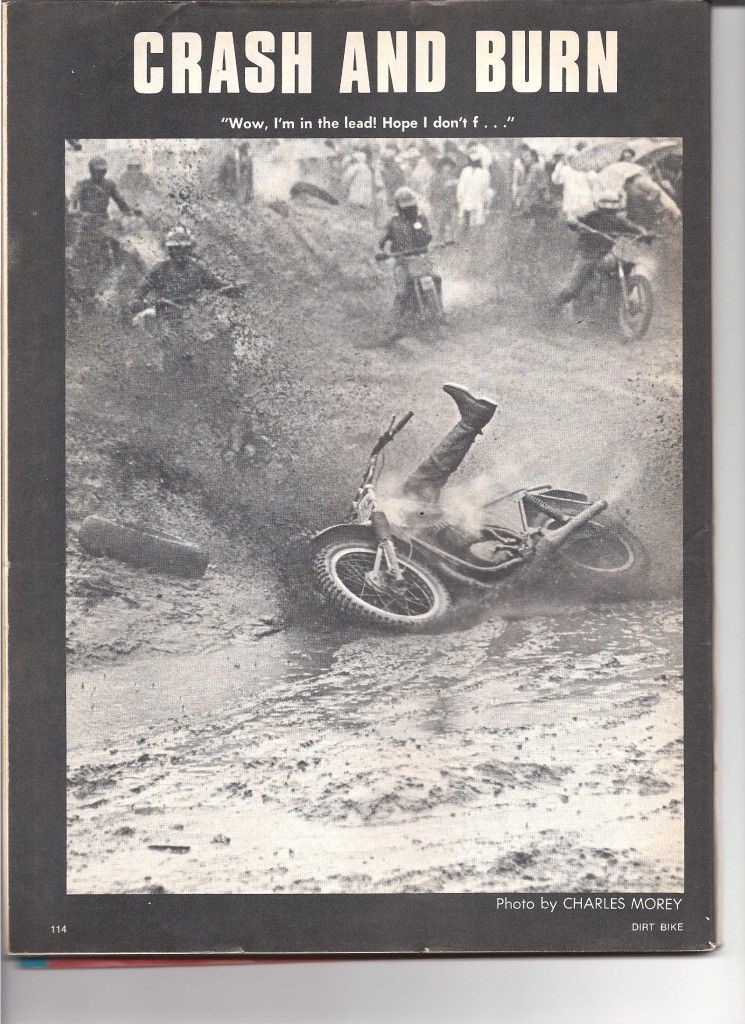

“Wow, I’m in the lead! Hope I don’t f…”

The story behind an iconic motorcycle photo

Do you remember this magazine, this monthly feature, and this particular photo? If you were riding dirt bikes in the 1970s (or desperately wanting one), of course you do! The magazine was DIRT BIKE, the feature was the last-page monthly “Crash and Burn” tidbit, and the photo was…well, the photo was the Crash and Burn image that set the precedent for stylish ‘crashing and burning’ on a dirt bike, in those early years of motocross in America. Recently, the plush and well-lit Vintage Motor Company office was graced with a fascinating response to our essay on DIRT BIKE Friends Talking: DIRT BIKE and Conversational Journalism, posted HERE, from visitor “czmx,” who, referring to the above photo, stated “I’m the guy in that photo!” Here’s the ‘rest of the story’ on this famous photograph!

Rusty McFarland may be known to some readers, from the excellent bio recorded by Michael McCook some years back (http://www.mccookracing.com/interviews/rustyMcFarland.htm), and also from a profile of Rusty and his CZ 250 restoration in Issue #20 of VMX Magazine. Rusty’s life is another ‘only-in-America’ story. Growing up near Memphis and in love with motorcycles, Rusty raced professionally for nearly a decade, before moving into the music business; first as a musician, and eventually as a multi-Grammy-winning record producer. But in the spring of 1973, Rusty—like many of us of similar age—was a teenager on a dirt bike.

In 1973, Rusty was 17 years old and already a Pro level rider. He had gone through a list of some memorable off-road bikes by the time he found himself the subject of photographer Charlie Morey in the famous image which introduced this essay. Starting on the little Honda his stepfather bought him, he had progressed through a Kawasaki 90 and then a G31M Greenstreak 100, a Penton 125, a CZ 250, Huskies, and was dabbling with Maicos. Little is written about the early motocross scene in the Midwest, but it was vibrant and nurtured its own roster of accomplished riders. McFarland—along with south-central stars such as Tony Wynn, Doug Wall, and Scott Jordan—could compete admirably with the western and eastern US stars, and weren’t afraid of the Europeans, either. McFarland, even by this young age, had regularly traveled the racing circuit around Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia and Florida.

In those days, as winter shut down northern tracks, motocross racers descended on the south in the colder months to race and maintain proficiency in the Florida Winter AMA series, promoted by the AMA. The six or seven seasonal races, over three months, gave racers a warm place to go, and the opportunity to try different tracks. Thus Rusty McFarland found himself heading to the second round of series, at the Orlando Sports Center, in March of 1973.

Arriving on Friday, the weather was good and the track acceptable—though it was the typical “flat, sandy, and whooped-out” Florida track. Practice and set-up went off with no problems. All that changed on Saturday night; the rains came, and didn’t stop. On Sunday morning, the monsoon-like rain was still coming down, and the track a “complete mess,” remembers McFarland. Nevertheless, he focused and lined up on the 250 Pro line, with the rest of the gate of 40 riders. Pushing the Maico to put down all it had, he hole-shot the start and found himself in lead, through the sea of muck. The start channeled to a jump, followed by a right-hand turn. McFarland cleared the jump, landed, and…realized his Maico’s throttle had stuck wide-open. He recalls:

“OK, I think…(in my youth and exuberance). A stuck throttle. No problem—I can do this. I’ll just ride using the kill switch and… (instant dump into a muddy hole!)”

As his theorizing on riding a stuck-throttle motorcycle was abruptly ended by physics, McFarland found himself under the bike on the right side, his head underwater, his helmet and goggles filled with muddy water, and holding his breath. No sooner had the thought “Am I going to drown in this hole?” passed, he raised his head, pulled off the goggles, and was able to regain his bearings. In fact, McFarland had been so far in front of the rest of the pack, with the stuck throttle motivating him (“they must have thought I was just crazy!”), that he was able to pull himself up and slog off the track before the first riders came up. As the bike had not only been submerged, but was screaming at full throttle at the time (which can be verified by noting the exhaust coming from the pipe in Morey’s photograph), it had ingested water in the engine and every other open space on the Maico, and there was no rejoining the race. Furthermore, given that McFarland had only rudimentary tools and parts with him, there was no choice for him that day but to load the muddy Maico back into his ’69 Chevy panel van and head for home. Unloading the bike the next day, back in Memphis at his parent’s home, brown Florida water poured out of the exhaust pipe.

Weeks later, in May, McFarland got a call from a friend: “I think your picture is in DIRT BIKE’s Crash and Burn this month.” (Back then, like now—for reasons only the publishing industry seems to understand—magazines dated ‘July’ would arrive in May.) And sure enough, when his own copy arrived several days later, there he was. His friend had recognized the bike by seeing just a hint of the 208L racing number, and the presence of the Husqvarna front wheel on the Maico. (McFarland must have been exceptionally photogenic that month: his picture also appeared in the July issue of Cycle Illustrated, accompanying a Daytona race review by Terry Pratt.)

Photographer Charles Morey travelled the early motocross circuit, selling photos to motorcycle magazines of the time, and is responsible for some of the most memorable images from 1970s racing. Together with fellow photojournalists Jim Gianatsis and Terry Pratt, Morey created a good deal of the important visual history of off-road motorcycle competition of the era. Rusty McFarland spoke with Morey about the Crash and Burn image several years ago. At that time, Morey declared that among his greatest motocross pictures were that of McFarland’s crash, and of course the acclaimed Tony DiStefano/Jimmy Weinert “banging handlebars” picture.

Looking carefully into the Morey Crash and Burn photograph and armed with McFarland’s recollections, additional details await discovery. Perhaps because of [Rick Sieman’s] subtitle (“Wow. I’m in the lead! Hope I don’t f…”), we may have tended to imagine the moment as simply a funny incident at a backwoods local race. In fairness, many Crash and Burn photos over the years did show amateur events. But in this event, as we’ve noted, the subjects are indeed Pro racers, at a national venue. Still, do doubt many viewers over the years imagined McFarland’s hapless character as just another Novice rider going down—vice an expert rider attempting to cope with a stuck throttle in the absolute worst riding conditions. Looking futher back in the image, one rider appears to be clearing mud from his goggles (or pulling a tear-off shield). The others seem to be slowly and carefully navigating the foot-deep mud ruts in an attempt to maintain forward momentum.

Other details are more difficult to ascertain. McFarland noted that he was wearing his prized Torsten Hallman leathers. He believes the boots (and possibly the gloves) were ASR (American Sport Racer, the sideline business started by Eastern Maico Distributor Dennie Moore in Pennsylvania).[1] These boots, leathers and gloves were significant improvements over the inflexible, black-only riding pants, “engineer boots,” and work gloves of just a few years prior. The new gear was padded in the right places and conformed to a rider’s anatomy—one example being the “pre-curved” gloves. And, in the case of ASR gear, they came in novel bright yellow and blue colors (reputedly taken from Maico’s star rider Ake Jonsson’s national Swedish colors, originally).

The motorcycle itself is a modified circa-1972 Maico 250 “square barrel,” the engine design immediately prior to the “radial” engine redesign, first released in mid-1972. The bike was provided by Dixie Maico in Nashville, Tennessee, and originated from Eastern Maico Distributors in Reedsville, Pennsylvania. As noted, it was equipped with a Husqvarna front wheel and hub, which apparently stopped better than the stock Maico unit. (McFarland noted that it would remain for Japanese motocross technology to introduce production brakes that actually…stopped.) We can see the engine is still running—at least it’s pushing exhaust out the pipe—and is of the old “round case” design (some late 1972 400 square barrels received the “sculptured” outer cases). The front suspension is Maico (not surprisingly, being the best original equipment units at the time) and the rear end has yet to be modified to the new forward-mounting/longer-travel configuration, which would sweep the motocross world in 1974. Given the mud spraying behind the bike and shooting aft from the front wheel, the bike appears to be still in motion at the time Morey’s camera shutter opened and shut.

We might also consider the meaning and context of the Crash and Burn feature itself, in which the photograph appeared. To “crash and burn” probably originated in aviation, but certainly applied to early automobiles and automobile racing, as well. The Crash and Burn section in DIRT BIKE Magazine generally treated the inevitable off-road riding “get offs” humorously and didn’t seek to dwell on life-threatening or clearly traumatic images—though some of the scenes pictured clearly might have resulted in serious injury. The editors sought to keep things light, and there was never any broken bones or blood shown. To that end, the Morey/McFarland image fit right in; certainly, there could have been some sore muscles after such a crash, but it was probably more amusing than tragic. It is, really, the classic “You shoulda seen me at…!” dirt bike bench-racing story. No harm, no foul; everyone laughed and walked away.

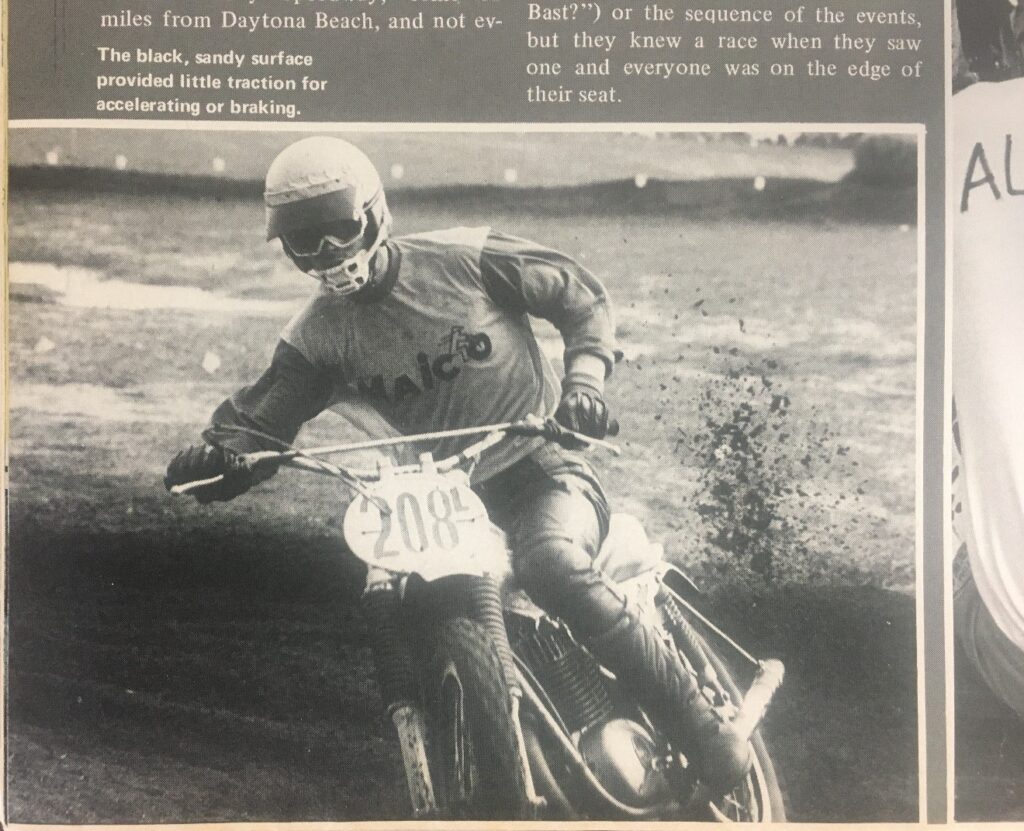

Soon after McFarland returned to Memphis, after his Orlando water adventure, he would receive one of the new radial-engined 1973 Maico 250s—one that was in fact supposed to have been set aside for Maico factory rider Hans Maisch.[2] McFarland modified this machine like he had his previous square-barrel, sans the Husky front wheel. Among the upgrades we can see are: aluminum tank (from the Torsten Hallman catalog, as he recalls), aluminum rear sprocket, alloy ASR or Wheelsmith chain guide and rear brake pedal, aluminum rear sprocket, possibly additional seat foam, plastic fenders, Wheelsmith bronze & steel foot-peg assemblies, and aftermarket grips.[3]

The Morey/McFarland Crash and Burn image has indeed become iconic. McFarland notes quite correctly that “Everybody remembers that picture!” Posters of the picture can be bought on eBay, and at the AMA Museum Gift Shop. Charlie Morey, now specializing in nature photography more than motorsports, not only confesses that this is his most famous photo, but also has placed the image on the back of his business card—just in case anyone forgets! One day it may certainly be less well-known, but certainly not until those of us who grew up with Rusty are still around!

[1] Dennie Moore owned Eastern Maico Distributors, Inc., the eastern US Maico distributor in Reedsville, PA from 1968 to late 1973. Ultimately, German Maico had forced Moore out of business, and set up their own distributorship, “Maico, East” owned by Otto Maisch, in nearby Lewistown, PA.

[2] Hans Maisch, one of the Wilhelm Maisch Sr. sons, raced the international 250 class as his contribution to the business. His brother Wilhelm Jr. was chief engineer, and another brother, Peter, helped in marketing.

[3] ASR vs. Wheelsmith. Since Dennie Moore (Eastern Maico and ASR) and Greg Smith (Wheelsmith) shared ideas on product designs, specifically identifying alloy items in particular from one company or the other can be difficult.

If you enjoyed the article, please consider “Liking” us on Facebook (link below) or supporting the Vintage Motor Company by checking out our t-shirts (hand-designed, original artwork) located here. It just happens that we think these are the coolest vintage bike t-shirts available anywhere – and many others agree!

Great story I was a younger rider in the days that Rusty and the other Pro ‘s mentioned in the Article that I would watch every weekend aspiring to Be as fast as them some Day. I remember the Maico and always enjoyed watching them Dice it out!

Thanks, Mark. I’ve been told that Maicos made up at least half of the gate at most open class Pennsylvania races in the 70s. Amazing for such a tiny company (about 250 personnel at their height).

Well, Mark Rakestraw certainly met his aspirations to be a fast pro motocrosser. I quit racing in ’76 to pursue a music career, but one Sunday in ’77, I came back out to our local track at Lakeland, just outside Memphis to give it another go. By then, Mark was a fast privateer touring the AMA Nationals. So I lined up against him and the rest of the 250 pro class, and towards the end of the moto, he and Bob Collie, another fast Memphis pro lapped my ass! I tried it again one more time about a year later in a mud bog of a race at the same track, riding my old nemesis, Doug Wall’s 370 Bultaco, and they handed my ass to me again. Between getting lapped, floundering around in the mud, and generally getting in the way of the faster, younger whooper snappers, I suddenly remembered why I had quit racing a couple years earlier. That was enough for me. I went back to my guitar, cranked it up, and licked my wounds.

Great article! I grew up in those times and even made my way to the Florida series one winter. I’ll never forget it. I also grew up in Ohio where mud races like that were common place. Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

Thanks, Brian. Glad you could connect. I confess I was a 15 year old, just dreaming at the time!

Hi David. I have called you a few times regarding some of the motorcycle (and non) related things we discussed on the phone during the interview. I suspect the number I have for you is incorrect. Please contact me at my email with you number. And thanks for the great article! That picture will probably out live me. Rusty McFarland

Hi Rusty, Glad you enjoyed the article! I’ll email you shortly. Thanks!