No products in the cart.

Ake Jonsson, German motorcycles, Motorcycle Culture

Ake Jonsson: King of Motocross

Part 1: The Success Years: Ake Jonsson

“Watch Ake slice inside his line and pass him, seemingly with no effort. What makes a man ride like this?”[1]

“I think Ake was probably the best motocross rider, ever.”[2]

The Vintage Motor Company is proud to release part 1 of a 2 piece series dedicated to in our opinion, the greatest motocross rider of all time; Ake Jonsson. To illustrate the uppermost level of the professional, factory-sponsored rider in the 1970s, there can be no better example than Ake.

His story reveals not only the life of one of the finest motocross riders in the world, but also the struggles and strategies of the small Maico factory as it competed against the giant Japanese corporations. Jonsson’s story is also a lesson in the unpredictable nature of motor sports competition.

RACING: HOPE, IMAGE, REALITY

The professional or “sponsored” rider is a professional athlete, paid to display his skills for the entertainment of fans and for the advancement of the sponsor; his job is to race, to place as highly as possible in the standings, and to be the public face of the brand. The professional rider, though racing as an individual, is generally also part of a team (usually that of the brand manufacturer in the 1970s, but sometimes that of a related business).[3] During the period of great interest in motorcycle competition in the early 1970s, all motorcycle manufacturers sponsored international teams as a way of both promoting and improving their product. Racing has long been considered an important way to validate the quality of a motor vehicle in the public’s perception. While successful results by amateur racers were welcomed and publicized by the manufacturers, there was no substitute for the public relations value of success in elite, international, highly-funded and highly-visible racing.

To achieve the status of being a sponsored rider was the dream of most any enthusiastic sport motorcycle rider, then and now. As is the case in other professional sports, only a tiny fraction of the aspirants will ever be good enough or fortunate enough to achieve full factory sponsorship. In off-road motorcycling in the United States in the 1970s, the premier motorcycle sport venue was undeniably motocross, and young American motocross racers shared this dream of being “paid to race.” Motocross had its roots in Europe, however, and the European riders were initially superior to riders from the United States. This was due to not only their experience, but also to their acceptance of the physical demands of the sport.[4]

In time, American riders would dominate the sport. In the early 1970s, though, the Europeans were the professionals, the sponsored riders and the stars. It was they who amazed fans as they travelled Europe and North America along the professional motocross racing circuit. Young aspiring professional riders in the United States watched the Europeans enviously, and some began racing with partial sponsorships from dealers and other businesses, or lived month-to-month on a combination of sponsorships and race winnings. Several of these riders will be discussed in the next few chapters. Denny Swartz and Brian Thompson pursued their dreams of following the professional circuit as partially-sponsored riders, enlisting the help of family. Other American racers, such as Tim Hart (read previous article: Motocross Looked Like This: Tim Hart) and Barry Higgins, were fortunate to enjoy “full” sponsorships, though their salaries and benefits were certainly not lavish, and they mostly raced mostly in the United States. At the very top of the ladder, and holding the position which all these riders aspired to one day fill, was the elite factory rider. He campaigned on the international racing circuit on the best machinery, earned at least a modest salary, and benefitted from the full resources of the sponsoring factory. In the case of Maico, during its glory years of the 1970s, these top-level riders included Germans Adolf Weil, Willi Bauer, and Hans Maisch; Dutchman Gerritt Wolsink; and the rider most often associated with Maico, Swede Ake Jonsson.

The Early Years

Ake Jonsson was born in Hammerdal, Sweden on October 5, 1942. Sweden was neutral during World War II, but the nation’s situation was hardly peaceful. Neighboring Finland, invaded by the Russians in 1939, fought on to recover lost territories while Norway was occupied by the Third Reich. Sweden managed a precarious neutral existence throughout the war. Her economy, however, was essentially militarized as a precaution, and production of military equipment took precedence over civilian goods.

The young Jonsson was drawn to sports, skiing and skating at every opportunity. The Jonsson family moved south to Vasteras, about 100 kilometers west of Stockholm, in 1956. Southern Sweden had less snow than Jonsson’s northern boyhood home, so he transitioned from skiing to the sport of speed-skating, a pursuit in which his older brother Arne was already involved. Jonsson trained hard for speed-skating, a sport requiring extreme stamina, and competed for about four years. Then, after he turned fifteen, he bought his first motorcycle, an old DKW. By age sixteen he had begun to compete a bit, and was riding a homemade Husqvarna. He achieved early success due to his physical conditioning for skating; something he would remember throughout his career. Eventually, since the competition seasons for speed-skating and motorcycle racing occurred at the same time, Jonsson had to choose one over the other. Motorcycle racing won out, he remembers, “. . . because it was more fun.”[5]

Jonsson discovered that he was a natural rider. He progressed in recognized skill level from Junior to Senior standing in 1963, which allowed him to compete for the Swedish national championship. Jonsson, however, shared a problem with most other young riders of his day: lack of both money and good equipment. The old motorcycle he rode as a Junior was woefully inadequate for higher levels of riding. Even if he had had the money, there were precious few competition motorcycles to buy at the time. The great Swedish Husqvarna company had just begun to produce off-road competition machines, but they were economically out of reach for an average young Swede.[6] Beginning a series of creative steps to remedy his dilemma, Jonsson decided to build his own motorcycle from parts. Purchasing a 250cc piston, he had older friends cast a cylinder, which they then machined to fit Ake’s piston. After attaching their hand-crafted top end to an old Husqvarna 175cc engine, Jonsson had his 250cc motorcycle (Figure 87). He modified the frame himself, fitting a Norton fork and Girling shocks, finishing his custom motorcycle. Racing this one-of-a-kind machine, Jonsson placed ninth in the Swedish championships that year. By virtue of his high standing in the 1963 season, he pre-qualified to start in every race in the coming 1964 season. Once again, however, he was frustrated by primitive equipment. The three-speed gearbox on his home-made machine could not compete with the new four-speed boxes then made by Husqvarna and being raced by his competitors. He had the talent, but needed a modern, competitive motorcycle.

Soldiering on, Jonsson trained hard all winter for the coming season, managing to save enough money to purchase at least a new Husqvarna engine with the new four-speed gearbox. Yet, he still did not have the resources for a whole new motorcycle. His current home-made machine had allowed him to almost beat Husqvarna factory star Torsten Hallman at the first Swedish championship race; quite an accomplishment. In so doing, however, his old Husqvarna’s Silverpilen frame had been reduced to a loose assembly of cracked metal tubing. Only about two weeks out from the next championship race, Jonsson thought to ask a friend “who knew people at Husqvarna” whether he might be allowed to purchase just a frame, to allow his by-now tired, homemade bike to run again. Jonsson heard nothing more until arriving home from school one day (coincidentally, the same school where Hallman was also studying engineering) and received a message from his mother. The Husqvarna factory had phoned, she informed him. Jonsson called back immediately, speaking with production manager Bror Jauren. “You can come down now; we have a bike here for you.”

Jonsson took off from school the next day to race over to the Husqvarna factory, undoubtedly one of the happiest teenagers in Sweden. There, he picked-up his brand-new, factory Husqvarna 250. Jonsson won the first race on his new motorcycle, won the championship race after that, and placed second in a following race. By then, with his new Husqvarna, he had decisively beaten Hallman and was the Swedish National Champion. Later that year, Jonsson was selected for the Swedish Trophees des Nations team, competing in Markelo, Holland, where he won the first of his six World Championship Team gold medals.

Continuing to attend school and race, Jonsson stayed with Husqvarna through 1968. He completed his engineering degree in 1967, but delayed entering the engineering profession and continued to compete. He kept placing highly, although his adjustment to the 500cc class in 1967 was a challenge. 1968 saw Jonsson back on top in the Swedish circuit, and competing internationally was the obvious next step. Yet, despite his successes, there again were substantial challenges. For one thing, the meager racing budget of the Husqvarna company left it unwilling to sponsor the young racer with anything more helpful than a limited supply of parts. Jonsson did all his own mechanical work at the time and was also paying all his own expenses, and he realized this situation needed to change. The Swede noticed that the German Maico company was active in international racing, and appeared to support its team better than did Husqvarna. Later that year, Jonsson’s manager contacted Maico to inquire about the possibly of a better sponsorship arrangement for Jonsson. Maico was interested. Jonsson soon found himself in Germany, testing a Maico, and an agreement for sponsorship for the coming 1969 season was reached.

The Maico years

1969 was a year of great readjustment for Jonsson. His new teammates were friendly and helpful all around, but his Maico 360 continually failed to finish races. “Everything broke down . . . in every race. . . . I was just unlucky with it. I don’t know. . . . Stupid things, which I knew shouldn’t happen.”[7] Despite the problems with the motorcycles, Jonsson noticed a very positive trait evidenced by his new team; that was the degree to which the entire Maico organization communicated and cooperated amongst themselves. “One thing that was good about Maico was that you could get so close to the R&D department. You could talk to everybody. Everyone was very familiar. We could see everything the racing department was doing; we were all very close. Adolf Weil and Willi Bauer were very good teammates. They helped me with everything; they were used to Maico. The basic bike was good, and we improved it; made it better and better. It didn’t take long . . .” One remarkable Maico employee in particular caught his attention. This engineer and racing enthusiast was Reinhold Weiher, who would be instrumental in the development of the coming Maico long-travel suspension and in many other aspects of Maico’s success. Weiher’s time at Maico was to be limited, but his impact on Jonsson and on Maico motocross machines was long-lasting. As Jonsson recalled, “They had a very good engineer at the Maico factory; a young guy named Reinhold.[8] He was also racing a bit himself, but was not that successful. He had one race in Germany, later, where he [was involved in a] crash; he died, accidentally. Very sad; he was tremendously good with the bikes. . . . That’s what marked the kind of people who built Maicos. When we came to the States, in 1970 through 1972, we had a very good bike.” Jonsson’s comment emphasizes Maico’s long history (and strength) of being a factory where riders built bikes for other riders. He knew both he and Maico were ready, as the German factory increased its presence in international competition.

One other early adaptation Jonsson had to make with the Maico hardware was with the clutch system. Earlier Maico clutches tended to require a very heavy pull. In response to customers and dealers who complained about the hard-to-work clutch, Maico designed a new, easier-pulling clutch in 1969. This clutch is often called the “large” clutch (and the earlier, harder-pull and smaller-diameter item the “small” clutch). The new large clutch certainly reduced the amount of clutch pull required, but it came at a cost. As Jonsson remembers of his early days on a Maico, “Willi Bauer and Adolf Weil told me, ‘You should get [the easier clutch], because you are not used to Maicos.” So, I got the [easier-pulling] clutch. Well, at one of the next races, I got to test Adolf Weil’s bike; his bike was so much faster than mine! I couldn’t understand this—we had the same cylinders, everything was the same . . . except for the bottom ends. There should have been no difference. It should have been the same. And then I figured it out: it must be the clutch [slipping and not transferring all engine power to the transmission]! You know, I had the [new] triplex chain with the bigger clutch on, and he had the old duplex chain with the smaller clutch, and the old crankcase cover. So, I changed my set-up back to the old clutch, and then my bike was as fast as his. From then on we used the old clutch all the time; that’s why we used the old [square-barrel] crankcase. The new clutch-transmission was taking away so much power . . . the bike was much faster with the old clutch.”

Thus, the easier-to-pull clutch sapped rear wheel power, due to slippage. Jonsson’s early Maico 360 was converted back to the old clutch for optimal power transmission. When the radial 400s appeared, a complete engine re-design, Jonsson’s racing bikes initially retained the old square-barrel bottom-ends, to allow continued use of the old clutch.

This combination was no simple task, as it required the four cylinder studs be re-located on the square-barrel crankcase to match the radial cylinder. The appearance of these unique motorcycles and the reason for the unusual combination of old and new engine parts have long been of interest to classic motocross enthusiasts. This modification to Jonsson’s engines is illustrated at Figures 91 and 92.

Ake Arrives in the States

Jonsson’s first exposure to racing in the United States came in 1969. He was by then comfortable with the venerable Maico 360, most of its problems having been mediated and the machine finally reliable. He found it lacking in power output, however, for competition at the international level. With his sights already set on the world championship, Jonsson considered this issue so critical that he was ready to leave Maico for the 1970 season, if no relief was in sight. Just prior to embarking for the United States in 1969, his complaints reached the ears of an older machinist in the engineering department, Gottlieb Haas. Haas, another successful competitor turned Maico employee, considered the problem and offered an easy solution. In order to achieve more power quickly and inexpensively, he proposed an old but ingenious idea: that they simply “stroke” the existing engine to obtain greater displacement. The basic concept, familiar to Indian and Harley riders in the United States decades earlier, was to move the crankpin (which attaches the connecting rod to the crankshaft) slightly farther out from the center of the crankshaft. This change increases total piston travel and, ultimately, displacement.[9] This plan required a minor redesign of the crankshaft, but allowed continued use of the existing rod, sleeve, and piston assembly. The idea was cheap, effective, and fast. By adding only 32cc of displacement, Haas created an engine with a completely different personality. Jonsson recalls, “I hadn’t even tested the bike. I went over to Boston, to that first race at Pepperell (Massachusetts); and that was the first time I rode that bike. I remember the straights . . . my arms were straight back [from the acceleration]! It was such a big difference from the old 360, you couldn’t believe it!”[10] Now, there was power enough to match Jonsson’s skills.

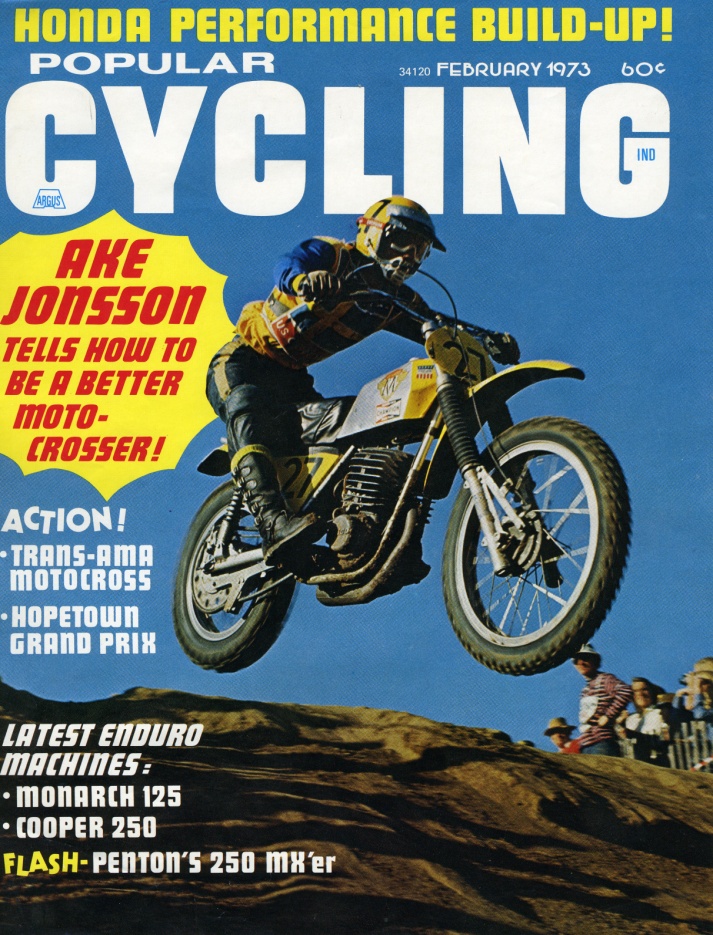

The 1970 season developed into a good one for Maico, now that the 400 bike was available. Jonsson scored wins all across Europe and was poised to take the world championship title. At the last race in Ettelbruck, Luxembourg, Jonsson experienced the kind of fluke occurrence that would repeatedly plague his world championship attempts: during the race, a fork tube loosened in the triple-clamp, coming up far enough to puncture the gas tank and costing him the win and the championship. Despite this personal disappointment for Jonsson, the Maico team did well, overall, and Jonsson continued to win other events. He returned to the United States for the fall Inter-AM series, taking that title handily and further cementing his reputation in American motorcycle racing. There was a definite glamour associated with the fast-moving Swede on board the stark German machine, not lost on American fans or the media. An interesting photograph from several years earlier caught Jonsson and fellow Swedish racers Torsten Hallman and Steffan Eneqvist with actors Jimmy Stewart, Raquel Welch, and Dean Martin on a movie set; no small amount of star appeal. From the outset, motocross in the United States brought a sexy, modern, athletic attraction. Jonsson and Maico helped this image, lending the circuit (along with his fellow European imports) an element of international interest at the same time that European automotive sports were seen across the culture as ultimately glamorous. This was a heyday in auto racing circles for European-style car racing in the United States, as well, with events such as the Six Hours at Watkins Glen, New York, which began in 1968. American movies and television shows featured European drivers and vehicles. Jonsson and his fellow European motocross stars conveyed this same colorful cachet to American off-road motorcycle racing, helping to elevate it above the old sweat-and-black-leather aura it previously conveyed.

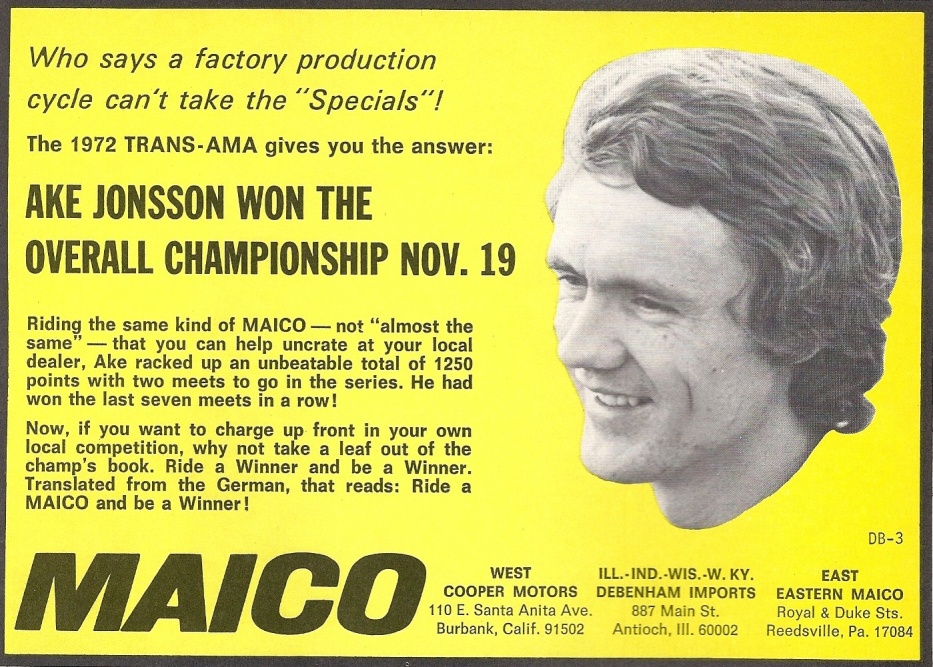

Jonsson’s motorcycle was famous, as well. His consistently-winning 400 Maico was one of the most photographed and analyzed factory machines of the day. The idea that this simple, stock motorcycle could do so well against the expensive, one-of-a-kind creations of the giant Japanese factories found purchase with the old individualistic, egalitarian, class-resistant sensibilities of United States enthusiasts. It was, quite literally, a motorcycle that an everyday rider could own, something the Maico advertising department was eager to highlight (Figure 93). The Japanese factory machines, especially the Suzukis of Roger DeCoster and Joel Robert, were elite motorcycles; thinly-veiled imposters, outwardly resembling the production machines, but in actuality the extravagantly-expensive and unattainable creations of massive Suzuki research and development efforts.[11] The factory Maicos looked strikingly similar to stock motorcycles, and, essentially, were exactly that. The Maico racing team, whether intentional or not, reinforced the point by exhibiting little concern with superficial paint scratches and the like, while the Japanese teams were fastidious about cosmetic appearances. This apparent disdain for superficiality again pleased American sensibilities (possibly touching upon anti-class feelings): the rough, outwardly-unkempt Maicos of common stock, beating the effete, image-conscious and unapproachable Suzukis and Yamahas. Translated into American history, it harkened to disheveled American frontiersmen facing down British aristocrats in battle—and winning.

Ake’s Maico: A Finely Tuned Machine

It is important to note, however, that while Jonsson’s machine, like those of the other Maico pilots, was created from standard Maico components. It was, though, very carefully built; made of precisely calibrated and tested parts. Jonsson used stock porting and engine parts as well, though he and Maico were periodically accused of employing specially-built pieces in his engine. Otherwise, went the reasoning, how could he possibly go so fast? In 1972, after the final series race at California’s Saddleback Park, Jonsson famously allowed the press to disassemble his championship-winning motorcycle. “I don’t remember what newspaper it was, but I remember reading how they took it all apart and examined it, and there were no special parts.” The magazine was MotorCyclist, and, aside from personal modifications, the magazine reported in March of 1973 that Ake’s bike was indeed entirely stock. To further make the case, the writers compared, photographed, and measured off-the-shelf Maico parts with those in Jonsson’s machine; they were found to match exactly.[12]

The comparison of the obviously very different motorcycles raced by the Japanese teams with those of the smaller teams, such as Maico, also suggested to fans in the United States two major points. First, if Ake Jonsson could regularly best DeCoster and his $30,000 Suzuki with an essentially stock $1,600 Maico, Jonsson was indisputably a phenomenal talent. Second, it confirmed the idea that the basic Maico was an excellent motorcycle, capable of winning on the international stage. And, most importantly, it was within the financial reach of the amateur rider. On a Maico, it appeared, anyone with enough talent had at least the chance to win. In a way, Maico brought fairness to racing; anyone could buy the same motorcycle Jonsson was riding. Maico’s success effectively democratized motocross racing, in the face of the exclusive and unobtainable Japanese machines.

Maico, like most other motorcycle factories, used racing as the ultimate laboratory in which to test the viability of new parts and ideas. Elite, professional-level racing was the ultimate test for any racing motorcycle. Furthermore, and equally as important, the rough and no-excuses caldron of professional racing improved not just the factory bikes; the lessons learned trickled down to and benefitted the entire line, racing or not.

Experimental cylinders (See photos) show the considerable experimentation (in this case with cylinder porting) that was being done in the 1971 through 1973 years. Jonsson notes that the factory also experimented with titanium axles, nuts, and bolts; and with aluminum swing-arms and exotic frames. Adolf Weil tested an all-alloy Maico frame, but it broke early-on and the idea was apparently abandoned.[13] Jonsson stated that, to the best of his knowledge, all testing was done in Europe, and not in the United States. The presence of the experimental cylinders suggests this might not always have been the case.

Jonsson’s personal alterations to his motorcycles included black paint on the engine (believed at the time to increase heat transfer), a custom steel rear brake pedal, footpegs moved 1 inch rearward, 1.5 inches additional foam on the seat, and his specially-made aluminum gas tank. Other changes could be effected as needed to suit individual tracks and conditions. The shock absorbers were Konis, with the damping valve altered at the Maico race shop, due to the stock valves’ tendency to break. Jonsson’s assigned mechanic in 1971 and 1972 was his old friend, Curt Oberg (Figure 90), who would later accompany him to Yamaha.

In terms of engine power, Jonsson remained comfortable with the 400 Maico’s power output, and considered this engine superior (for his purposes, at least) to the more powerful 440. He was certainly familiar with the 501, but rode it only for publicity events and never raced it. Maico experimented with another 500cc engine in 1970, Jonsson recalls, which was different from the 501 and legal for the European championships (where capacity could not exceed 500cc). Like many other industry experiments with massive, raw power output, Maico found that a good racing motorcycle does not necessarily respond well to additional horsepower: “That bike (the 500cc engine in the standard Maico chassis) was bad-handling; it just wasn’t possible for the bike to handle all the power. It also had the wrong power-band.” The Yamaha team, which Jonsson would soon join, dealt with this conundrum as well. Yamaha leadership, new to motocross but accustomed to road-racing, seemed to believe that the highest power output by itself should ensure race wins, as it generally did in road-racing.[14] They would see this idea proved wrong.

If you liked this article and others written exclusively for you vintage motocross fans, feel free to support us by purchasing one of our hand designed t-shirts! For starters, check out our 1981 Maico 490. We truly feel these are the best vintage bike shirts available!

[1] Dirt Bike Magazine, “Ake, The Top Moto-cross Jockey,” Dirt Bike Magazine (March, 1973), 27.

[2] Interviews with Dennie Moore by Ake Jonsson, March 27, 2007 through November 14, 2013, Lewiston, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[3] In the 1970s, teams in professional motocross, other than those sponsored by manufacturers, included related businesses such as Wheelsmith or ProCircuit. More recently, teams are often organized around an unrelated product, seeking to associate itself with the glamour of motor racing (Team Monster Energy or Team Rockstar).

[4] The forty to forty-five minute motos (heat races) in motocross were far more demanding in terms of muscular endurance and cardio-vascular fitness than the short duration scrambles events which preceded motocross in the United States.

[5] Interview with Ake Jonsson by David Russell, November 25, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[6] The old Husqvarna company, located near the village of Huskvarna on the shore of Lake Vattern, Sweden, began by producing arms for the King of Sweden in 1689. Like other arms manufacturers, such as BSA and CZ, the Husqvarna factory was in an advantageous position to move into machine production (and motorcycles, specifically) in later years. Husqvarna, like Maico, was an early producer of high-quality, lightweight competition motorcycles. The 165-pound Husqvarna “Silverpilen” (Silver Arrow) was the introductory sporting machine for many European racers.

[7] Dirt Bike Magazine, “Ake Jonsson, Top Moto-cross Jockey,” 26-33.

[8] Maico held Reinhold Weiher in very high esteem. After his death, Wilhelm Maisch Jr. offered his brother Frantz Reinhold Weiher’s former position, and Frantz accepted.

[9] The term “stroker,” in biker lexicon in the United States, refers to a motorcycle engine which has received this modification.

[10] The longer-stroke 400 (actually 386cc) used the same bore as the 360 (354cc). Maico 360, 400, 440, and 490 models share an identical rod assembly.

[11] Terry Good, Legendary Motocross Bikes (Minneapolis: Motorbooks International, 2009), 23-41.

[12] Jonsson’s championship bikes were examined by the press in this way on at least two occasions. The first published examination was in Cycle Illustrated in July, 1971 (“A Very Special Maico”), dissecting the #4 square-barrel motorcycle. The champion #27 radial motorcycle was taken apart by MotorCyclist, and reported by Dave Holeman in the March, 1973 issue (“The Incredible Ake Jonsson and his Magnificent Maico”).

[13] Jonsson refers to Maico testing a titanium frame in the Dirt Bike Magazine interview (Dirt Bike Magazine, “Ake Jonsson, Top Moto-cross Jockey,” 26-33) and to Weil testing an alloy frame in his interview with the author (Interview with Ake Jonsson by David Russell).

[14] Colin MacKellar, Yamaha Dirt Bikes (London: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1986), 38, 42. Among Yamaha’s other notable attempts and failures in this direction were the 1972 490/420 factory bikes that Jaak Van Velthoven was “happy to leave on the trailer” at the races, and the ill-fated SC500 production bike, the “big, bad apple” with the “forty-horsepower on/off switch” of 1972-3.

I love the rush and excitement that comes for riding a motorcycle bike! You have a great website for people who love motorcycles and vintage ones. How did you get involve with vintage motorcycles? I wish you and your family the best in your business, and I know you will do well!

Thanks Zoey! To get involved with vintage bikes… lots of riding, passion, and sweat!

Found this through Tim Hart obit. RIP. Raced a 1971 250 Maico in Ohio for two seasons. Won 6 times. Never had a “Maico-breako” issue. Handled better (corners) than Husky’s and faster (tractable) than CZ’s. Clutch? Only for starts (!). Was told by dealer/sponsor – “Start with clutch – then bang up and down without it in race.” Worked great! Ake Jonsson had a book; “Art of Motocross” or something. Wore it out, read so much. He (& Maico) was the Smoooothest duo on the track. Like butter. Thank you/bless you, Mr. Russell, for these golden memories.

Thank-you, Richard. I recall Tim saying that reliability really wasn’t much of a problem with his Maicos–but then, he remembered tearing them down each weekend!

I raced a 250 square barrel from 71 to 73 and then a radial 250 in the mid 70’s, never had a break down. Just kept everything tight and adjusted. But I didn’t try to modify anything other than different shocks. I think some breakdowns are from trying to hard to make the bike faster instead of just admitting “that’s as fast as I can go”. My claim to fame was staying with Mark Barnett for a few laps when he was brand new, until he got bored as was just GONE. Realized I was for sure a hobby rider.

Wow, very engaging article on one of the gods of motocrosss. He was from the we’re if the Ironmen when bikes weighed 260 pounds. But he also see the transition to unobtanium metals and weights just about where we are today.

Vet cool that you mention Brian Thompson, the first Black AMA Pro motocrosss racer. He and his brother Brett raced the Nationals before James Stewart was even born.

You guys got a new fan, terrific article.

Michael James

ex Cycle News writer & columnist

Thanks so much, Michael! I was honored to interview Ake, and I’d love to meet him. Gig Hamilton’s memory of Ake riding a 40min moto in summer weather, and seemingly still not tired–with a “single bead of sweat on the back of his neck” always stuck with me. And, yes, BT is a local legend with us; he still retains the largest stash of old dirt bike stuff in the known world, we believe! Most sincerely, Dave