No products in the cart.

Uncategorized

The Motorcycle and Man: A Social History (Part 2)

The United States after World War II had become a consumption-oriented society. There were better wages for most workers, a high standard of living, inexpensive mass-produced goods, and a culture infused with the appropriation of material goods. Available to Americans at the time were a myriad of exceptional motorcycles from around the world. Each country counted at least one major motorcycle manufacturer. These manufacturers had likely been involved in armaments production during World War II or wars several centuries past, and were accustomed to industrial machine work done to high tolerances. They were likewise familiar with modern materials such as plastic, aluminum alloys, and chrome-molybdenum steel, essential ingredients in high-performance motorcycles. The world motorcycles of this period of growth and experimentation reflected a variety of approaches to common engineering challenges, and, unlike modern homogeneous motorcycle designs, looked and performed very differently than machines made in the other countries.

The Europeans Thrive, the British Retreat . . . and the Japanese are Coming!

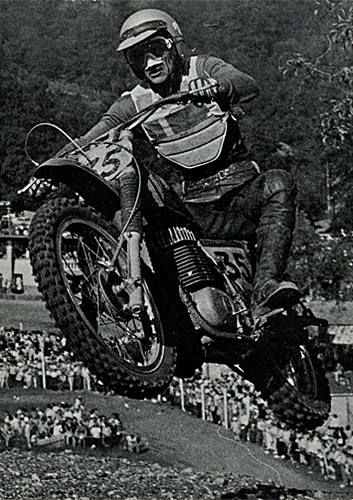

Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, interest in and sales of motorcycles increased. With American brands Harley-Davidson and Indian giving only marginal effort to the competition for smaller off-road models, small makers in Europe fought for this United States-free vacuum in market share.[1] A very large portion of this non-American production, fifty percent or more, in the case Maico, for example, went directly to the United States.[2] From Sweden came the Husqvarna, a high-quality machine made by the old Husqvarna weapons foundry; usually red and chrome, expensive, and with a reputation for high-end quality; and also the jewel-like, yellow and blue Monark.[3] From Spain came three high-performance motorcycles, their beautiful fiberglass bodywork always colorful and their highly-tuned (and highly-stressed) engines often providing only minimal longevity: the Bultacos, Ossas, and Montesas. Austria produced the solid and well-engineered Puch and KTM machines. Japan, whose motorcycle industry began in earnest after World War II and was moving inexorably to a domination of the world market, exported exquisitely-made motorcycles which, though somewhat deficient for serious off-road use in the late 1960s, were only getting better. Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki, and Yamaha produced very good machines at excellent prices, their sales especially aided by world currency fluctuations in the mid-1970s.[4] Typical of the Japanese technological style of the time, these motorcycles captured one segment of the market after another, beginning with the smallest machines. This tendency of the British manufacturers, up until then the largest exporter of motorcycles in the world, to yield one part of the motorcycle market after another became what Steve Koerner, in his study of the collapse this industry, would refer to as “segment retreat.”[5] Convinced the loss of one after another market segment was unavoidable or inconsequential, the British continued to narrow their offerings, until they only produced high-performance motorcycles for young males—too small a market to allow survival. Even that small economic outpost, in time, was conquered by the Japanese.

Honda’s Home Run

Honda, in particular among the Japanese makers, positioned itself for success in not only the on-road market, but in off-road sales as well. Honda engineers had already created a reputation of building exceptionally well-executed interpretations of what they believed buyers wanted, even if they sometimes misjudged the buyers’ actual desires.

Early Honda dual-purpose bikes, like those from Kawasaki, Suzuki, and Yamaha, tended to be over-equipped with superfluous niceties (such as large horns, turn signals, and oversized and heavy tail lights), be overweight, and be designed around a tiny Japanese rider on a perfectly smooth trail. Now, carefully assessing the attributes of successful motocross motorcycles and the real needs of the users (though having virtually no past experience in two-stroke engine design) Honda crafted one of the most impressive motorcycle new-releases in recent history. The 1973 Honda “Elsinore” CR250 and CR125 motocross bikes, named after California’s Lake Elsinore riding area, were nothing short of phenomenal when released. The 125 immediately and for several years hence rendered all other 125cc machines outmoded.[6]

Czechoslovakia produced the CZ and Jawa motorcycle lines. These sturdy bikes recalled farm implements of Communist-block manufacture, with their simple, rugged construction. They were fast (though heavy), and were able to endure the harsh terrain of the new sport of motocross. CZs were among the first two-stroke engined machines to displace the four-stroke motorcycles, then dominant in the sport, in the early 1960s in Europe.[7] Great Britain continued to produce BSA, Triumph, and Greeves off-road machines into the 1970s, but the once-dominant British industry was clearly dying, a victim not only of Japanese competition, but also of poor management, nasty labor relations, lack of quality control, sluggish market response, and similar currency devaluations as were plaguing Germany.[8] Smaller independent British makers, such as Rickman, CCM, and Cheney, however, made expensive and respectable limited edition machines for off-road use. Germany, the home of the BMW street motorcycle, made the very competent DKW, Hercules—and the Maico. America imported Harley-Davidson-badged Aermacchi lightweight motorcycles, and John Penton designed the Penton motorcycle around an Austrian KTM baseline, a well-designed all-purpose dirt machine but rarely a professional-level finisher in motocross.[9]

Maico: just a little bit better

Amidst this sea of beautiful and technically-advanced motorcycles, one brand quietly stood out among American competitors. This was the German Maico (the name derived from Maisch & Company, and pronounced “my-co” in Europe and “may-co” in the Americas). The bikes were expensive, but by the 1970s were recognized as the off-road standard to which the myriad other companies and motorcycles aspired. Maico concentrated on off-road motorcycles from the early 1950s, after it received a lucrative (and timely, given financial troubles at the time) contract for thousands of such machines for the German Army’s tactical use. This experience left the company well-positioned when lightweight machines became popular again and motocross captured the world’s fascination. At the same time, however, Maicos were recognized as being sometimes haphazardly assembled, prone to include oddly-deficient components, and having a tendency to fail if not fastidiously cared for. Spots in the paint and carelessly mounted decals were routine on Maicos. In some cases, they were twice as expensive as a precisely assembled, cosmetically perfect, and reliable Japanese motorcycle; as well as being much more likely to break down, if ignored. Yet, when handling and power were considered and the machine properly maintained, the Maico was believed by riders to be the finest off-road machine available.

[10] American riders sought out the Maico, in some years buying all the machines that the small company could import into the United States. Maicos became synonymous with no-compromise quality amongst off-road motorcyclists, both in the United States and abroad. They sold well, and developed a strong following in the United States during the boom years of 1968 to 1974. Former riders now recall that at least half the motorcycles on the starting line of a typical Expert 500cc class motocross race in the mid-1970s would be Maicos.[11] Maico was the first company to implement long-travel-suspension in its production machines, and the bikes were routinely shipped to Japan for tear-down, analysis, and copying. The 1981 Maico 490cc motorcycle is considered by many motorcycle experts to be the finest motocross motorcycle, for its time, ever made; the basic frame geometry and dimensions established with the 1981 model Maico are the basis for and are incorporated into all competition off-road motorcycle designs to this day.[12]

Two years after producing this benchmark motorcycle, the Maico company entered bankruptcy. Poor management decisions, family infighting, and a complex array of external factors had been at play since at least 1970, and finally combined to defeat the machine which had been so difficult to best on the racetrack. To the brand’s American fans, had they known, the intrigues then occurring at the Maico factory in Pfeffingen, Germany would have been hard to believe.

[1] Sucher, The Iron Redskin, 137-8. American companies had long produced smaller motorcycles (such the Harley Hummer, the Mustang, the Cushman scooter, and motorized bicycles such as the Whizzer). As the 1950s merged into the 1960s , however, the Japanese and other foreign makes were simply much better and cheaper.

[2] Interview with Wilhelm Maisch Jr. by David Russell, (date not recorded), 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[3] Lindstrom, Husqvarna Success, 83-108.

[4] Interview with Brian Thompson by David Russell, November 5, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[5] Steve Koerner, The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry (Lancaster, UK: Carnegie Publishing, 2012), 1-8.

[6] Interview with Brian Thompson by David Russell.

[7] Paul Stephens, Moto-Cross: The Golden Era (London: Osprey Publishing, 1998), 187-200.

[8] Koerner, The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry, 1-8.

[9] Youngblood, John Penton and the Off-road Motorcycle Revolution, 77-92.

[10] The theme of Maicos being the finest, even if flawed, machines available runs throughout this dissertation. An example of this sentiment is John Barclay’s remembrance in chapter 5.5 of the wide-spread belief among European professionals at the time that to win on the Grand Prix level, a rider “needed to be on a Maico.”

[11] Interview with Craig Shambaugh by David Russell, September 11, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[12] Interview with Selvaraj Narayana by David Russell, June 27, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg). Other authorities referenced in this dissertation to proclaim the 1981 Maico 490’s pre-eminence include professional racers Barry Higgins and Brian Thompson.