No products in the cart.

Early Motorcycle History, Motocross Des Nations

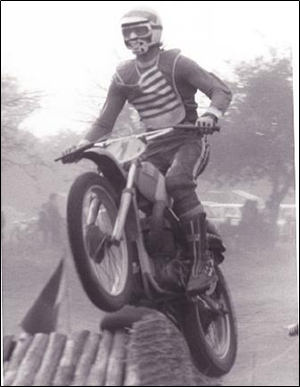

Innocents Abroad: The American Motocross Team in Europe

“. . . the American character is in a large measure a group of responses to an unusually competitive situation.” David Potter

While the new off-road sport of “Moto-cross” was sweeping across the United States, the presence and superiority of the elite European stars (brought over to publicize the sport and the European purebred bikes) accompanying it was not lost on the best American riders. Even if the young Americans were the best in their state or even their country, they could still expect to be regularly humiliated by the Europeans. In fact, in the years until around 1972, United States riders generally rode in a “support class” of 250cc riders, matched with mostly other American riders, while the Europeans competed—mostly against other Europeans—in the main 500cc class. Seeing this, some of the rising American competitors were of the mind that if they were ever going to beat the Europeans, they would have to go to Europe and learn, first-hand. They’d then be far better prepared to excel in the new sport; the summer in Europe would be fun, as well! Three of these young United States riders; Bryan Kenney, Barry Higgins, and John Barclay; did just that, and here is their story. (A fourth “American,” newly-arrived Swede Gunnar Lindstrom, was enlisted to guide them in their efforts, and will appear as well.)

Europe to America–and back again

America’s attraction to Europe, beyond motor racing, has always been strong, if not also occasionally conflicted. In the 1700s and 1800s, affluent Americans could not be considered cultured until they visited England and France, and preferably experienced an entire “Grand Tour” of the European and Mediterranean countries. Today, we imagine our ancestors and the countries our desperate relatives abandoned, years ago, in pursuit of the better futures they hoped awaited them in the United States. Americans still regularly tour Europe. Few of us do not have some European heritage in our family tree; we yearn to unearth these roots, and to discover our ancestral cultural context. We feel a desire to experience the “old country” that left us a heritage.

And Europe still affects America, even as America overwhelmingly leaves her economic and political impact on Europe. Whatever superiority we grant our newer, fresher, less-encumbered, “democratic,” and supposedly non-derivative cultural inventions, Americans continue to look over their shoulders at the old world. Europe remains an answer key to persistent questions on style, food and the classical arts. French and Italian fashion developments seems to garner immediate respect in New York, and an accepted European novelist must be acknowledged in American literary circles. Certain countries have reputations for particular areas of excellence: Scandinavian minimalist furnishing design, English political thought, and German engineering, are examples. Europe, as the ancestral origin for many Americans and still a cultural beacon, holds an undeniable attraction for us.

Simultaneously, the United States also places a premium on cultural independence from other countries. Americans do not like to think of themselves as imitators or inferiors. We have had time to develop our own culture, technology, and political system; quite superior, we may feel, to others. In the case of motorcycle technology, America had seventy good years to flourish of its own accord by 1970. The American motorcycle, adapted as it was to longer, rougher roads, independently evolved into a large, heavy, and powerful machine, different from those produced for European environments. Competition events came into existence in the United States as the natural format suiting these machines, and the oval horse-racing tracks already in place at fairgrounds around the country. Flat-track, hill-climbing, scrambles, and drag racing all catered to these large American motorcycles. When smaller European motorcycles began to appear in the 1950s, riders immediately took notice. These machines, mainly from England and Germany, were lighter and had advanced two-stroke or overhead-valve four-stroke engines, which gave the interlopers better power-to-weight ratios than the generally larger American motorcycles. Placed side by side with the native Indians and Harleys, the European machines could be decidedly superior off-road, and often far better in other forms of racing and riding. As the 1960s wore on and European-imported motocross absorbed much of the popularity of traditional United States forms of competition, sport riders found themselves not only possessing the wrong skill sets, but riding the wrong machines.

Scrambles racing and the birth of motocross in the United States

In the United States and Canada, the nearest equivalents to motocross were scrambles or “TT scrambles.” These were also closed-circuit, meandering courses, but over a shorter manicured surface, with gentle jumps and only a few gradual turns. Most any motorcycle could compete in scrambles, and interest in scrambles in the United States sports riding continued through the mid-sixties. In 1965, California businessman Edison Dye became the importer for Swedish-made Husqvarna motorcycles, a company that built off-road/motocross bikes, but had previously (and curiously) resisted entry into the American market. Dye brought his first two machines into the United States early in 1966. By the fall, Dye had imported fifty units. Dye was aware of scrambles racing, but felt that motocross would take off wildly in the states, once American were exposed to it. Thus Dye shrewdly decided to create the market for his new motorcycle by aggressively introducing motocross to America, the type of racing the Husqvarna was built for. That same year, after paying Husqvarna factory racer Torsten Hallman to come to the United States, Dye sent more riders throughout the country, organizing races and showcasing the skills of Hallman and other European riders.[1] The Europeans, accustomed to the longer, harder motocross heat races and riding motorcycles made to cope with it, at first made even the fastest American riders appear pitifully inferior. Hallman, and soon after fast-learning Americans like Californian Husqvarna-convert Malcolm Smith, riding their thoroughbred Husqvarans, dominated most every motocross or desert race in which they were entered. Seeing the immense commercial possibilities for both Husqvarna and motocross, Dye created the Inter-AM North American motocross series in 1967. The United States had witnessed motocross and loved it; the European import sport was defining itself as a new American institution.

The lure of Europe–and motorcycles

Among those Americans afflicted with the motocross bug at the time were three young men from different parts of the United States. Bryan Kenney, from Cleveland, Ohio, was a junior at Emory University in 1964, when he convinced his parents to grant him an early graduation gift: a summer abroad in Europe. Already a motorcycle enthusiast, he stopped by a few motocross events after his arrival in Europe which, he says, “totally knocked me off my feet.”[2] For Kenney, the events were life-changing: he arranged to stay in France and entered the University of Grenoble in the fall of 1964, in order to be able to race in Europe. For the next seven years, except for a return to Emory and later graduate work in California, Kenney lived much of each year in Europe, racing. His university might not have awarded a degree in motorcycling, but Kenney effectively majored in that topic.

John Barclay, from southern California, first encountered motocross in the late 1960s. This was after its promotion there by Dye and the members of the California Motocross Club, the CMC.[3] Barkley rode in the desert and in local motocross events throughout his time at college. Upon graduation in 1971, he married his girlfriend, Peggy, and the two decided that they should take a vacation/honeymoon to Europe. Since Barclay was already an avid racer and was familiar with Dye’s remarkable Husqvarnas, he decided he would purchase a new Husqvarna at the factory in Sweden, and “pick up a few club races” as they traveled.[4] Prior to departing for Europe, Barclay happened to make the acquaintance of American racer Russ Darnell, who was not returning to Europe for the next season. Darnell agreed to sell Barclay his old car and trailer, along with extra motorcycle parts, and to prime Barclay on the business end of racing overseas. Barclay would return to Europe two more summers after his initial 1971 trip.

Barry Higgins grew up in Kinnelon, New Jersey. As a boy, he rode with his father, Harry, and was quickly recognized as a prodigy on a motorcycle. Sponsored as a racer during his high school years, Higgins worked at motorcycle shops and married immediately after graduation. His wife’s prejudice against racing was too much for Higgins, and the marriage ended in short order. He, like the others, then discovered motocross, and in four more years, in 1969, Higgins was considered the top American motocross rider. For the 1970 season, Higgins was awarded the first-ever full-time racing contract paid to an American rider. Paid $100 a week to race, drive to events, and maintain his own motorcycles by the American Ossa motorcycle importer, Higgins was the envy of many young American men. In early 1971 he happened across Bryan Kenney, who convinced Higgins that they had to go to Europe that summer and represent their country in the Motocross des Nations, a team motocross event, as a member of the Kenny’s newly-formed “American Motocross Team.”

World’s Greatest Motocross Racer!

Checking into a hotel in Memphis, Tennessee, a month later for a local race, Higgins was handed his keys by front desk clerk Jeanne Lokey. Higgins, whose manager had announced him as “the world’s greatest motocross racer,” came back to the desk a while later. He asked Lokey if she might like to actually watch a motocross race the next day. Lokey responded that she certainly could not accompany him, as the next day was Mother’s Day. “Well, just leave flowers on your mother’s porch, with a note saying that you’ve gone to the motocross race; she’ll understand,” Higgins instructed her. Lokey did so, and experienced her first motocross.[5] Her mother’s reaction remains unrecorded for posterity. But Lokey in any case loved what she saw at the track.

Meanwhile, Bryan Kenney wasn’t finished with assembling his team. Having connections with American Husqvarna, Kenney contacted the company and their world-traveling engineer/racer/troubleshooter, Gunnar Lindstrom, and explained to the executives how Lindstrom’s abilities would round out the team. Lindstrom, who was not actually American, but possessed a green card (and was at least in America at the moment), was American-enough for Kenney; the execs agreed, and Lindstrom was recruited.

Meanwhile, Higgins and Lokey kept in touch. A few weeks later Higgins asked the twenty-seven-year-old Lokey if she might like to go to Europe for a few months. Lokey quit her hotel job and joined up with Higgins. She found herself landing in Luxemburg shortly thereafter in July, 1971. Meeting up with Bryan Kenney and his wife, Lori, in France, the four entered the European motocross circuit.

The European Motocross Circuit; an Explanation

Motocross races at this time were held throughout the European continent, from the Scandinavian countries in the north to Italy in the south, organized by either local clubs or individual promoters. International motocross meetings were the most common, attended by both professional and factory-sponsored riders, and also by non-sponsored individual riders, sometimes on their summer vacations. Grand Prix (GP) meetings, where riders competed to accumulate points towards the FIM World Championship, occurred once each season, with one event held in each country.[6] Finally, National Championship meetings occurred weekly in the various countries, with participation limited to nationals of that country, who were accumulating points and vying for their national championship. Since non-citizens could not, by definition, participate in the European National races, and the GP races only occurred once in each country per season (and did not pay much, despite their prestige), International meetings were the favored event of the American racers.

Life on the international motocross circuit, limited to Europe and the USSR at the time, was a glorious summer adventure for everyone, including the Americans. It was a modern, democratized variation of the Grand Tour, taken mostly by amateur enthusiasts in second-hand automobiles towing motorcycles, each weekend rejoining the same new and old friends. American racers had come to Europe in small numbers for years; Kenney was an early example (along with riders to include John DeSoto, Mark Blackwell, Russ Darnell, Mike Runyon, Billy Clements, and Jim Pomeroy). Later, Brad Lackey and many others would come to seriously pursue the World Championship (as Lackey successfully did in 1982), or to participate in the Motocross des Nations. The Americans were, however, a minority. All the racers from the various countries and those accompanying them migrated together across Europe, from race to race. Usually traveling throughout the early days of the week, they would plan to arrive at the next venue by Thursday or Friday. Once at the site of the next race, the riders would set up camp and prepare the bikes and themselves for the race; only an affluent minority stayed in actual hotels or under a roof while at a race. The travelling community enjoyed one another and the continual change of locale. The Old World travelers’ adventures were not unlike that of the New World surfers in the previous decade’s famous documentary, Bruce Brown’s Endless Summer. [7]The surfers in Endless Summer (like the motocross racers who would be portrayed in Brown’s later movie, On Any Sunday), canvassed the earth’s beaches in search of the perfect wave; camping, discovering, and making a virtue of the shoestring-budget and impromptu nature of the entire affair.[8] Motocross in Europe was no different, and the few Americans involved brought along their best pioneering instincts.

Practice was held on Saturday and Sunday mornings. Riders attended to details on their machines, while wives and girlfriends cooked or sat around the campsite. Soccer games, bicycle races, and volleyball punctuated the days. Language barriers often crumbled, depending upon the Europeans’ skill with English and the universal sign language of men speaking about machines. Accommodations were minimal, but this apparently only added to the adventure. Portable restrooms were rare, and even one such facility at a race, ridiculously inadequate in light of the possible 10,000 attendees for the Sunday race, was reason to be thankful. (Jeanne Lokey recalls many baths taken in streams during her motocross summer of 1971.)

Life on the European road

Lokey, Higgins, and Barclay remember the travel as pleasant, with good food in at least the northern European countries, and friendly welcomes by the local populations. Gasoline for the small cars was incredibly high-priced in the eyes of the Americans, but hotel rooms could be had for two dollars a night—when they had money in their pockets. The Kenneys and the Barclays both towed small trailers, called “caravans” by the locals, while Higgins and Lokey made due in their small van.

Eventually joining up with Higgins, Barclay, and Kenney as the forth member of the American Motocross Team’s entry in the Motocross des Nations was Gunnar Lindstrom. Lindstrom was working for Husqvarna at the time, and the company had kindly allowed Lindstrom to help out the team while on the payroll. If Kenney was the officially appointed “captain” of the team, Lindstrom was something of a team guide and mentor. Lokey remembers Lindstrom as the “calming force” among the Americans. Lindstrom’s racing skills were augmented by his multi-lingual ability, his understanding of the European racing business, and (especially fortunate for the members of the team then riding the Swedish motorcycle) his direct communications line to the Husqvarna motorcycle factory. Lindstrom was only in Europe for the Motocross des Nations and one British GP; other than this short period, the Americans traveled together and were on their own for the 1971 season. In 1972, Higgins and Lokey stayed home, and the remaining two couples continued together.

Beyond all the cultural and business differences to which the riders had to acclimate were the sheer physical demands of European motocross. Higgins, in particular, had been brought up on gentle, sweeping American scrambles tracks, where a normal heat race was five short laps. Throughout 1971, he was still adjusting to the exhausting European motocross rules of two forty-five-minute motos, plus two laps. Barclay took time to build his strength, as well. Kenney and Lindstrom, with the longest exposure to the European system, were aware of the endurance required and were by then physically up to the challenge.

John Barclay remembers the racing circuit as an international “community;” a vast cross-cultural youth movement with a shared interest in motorcycles. And, to this community, racers from the popular United States were both few and fascinating to everyone. Barclay recalls that it was the Americans’ situation as racers—a more popular identity than that of the caricature of the “rude American tourist”—which opened doors and ensured friendly relations with local populations. They thus enjoyed being motocross insiders, yet also being American and in Europe. Likening their status to that of professional athletes (which they truthfully were, although with minimal pay), Barclay remembers fondly that “everyone wanted to be our pal.” Along with the European participants, the Americans were toasted and entertained by local mayors, cafes, racing enthusiasts, and an energetic, ever-present fan base throughout their travels. The Europeans’ heightened appreciation of motorsport was deeper ingrained in the mass popular culture than in the United States. While Americans at the time also admired motor racing stars, their appreciation seemed limited to only a very few top figures. The Europeans were interested in everyone.

The Americans loved being Americans. Nationalism could be infectious; Lokey recalls that the first thing she and Higgins did upon being given the keys to their 1967 Volkswagen van was to “Americanize” it, painting a huge American flag on each side.[9] She recalls a pervasive pro-American sentiment in Europe, and felt that “Americans were loved everywhere across Europe, with the possible exception of France.” She also remembers that every time the riders set up a new campsite/pit area, “the first thing [the riders] would do was put up a flag of their country.” At the Motocross des Nations and the GPs, the grand opening ceremony pageantry far exceeded most American sport programs, then or now. Pigeons were released, flags were flown, and the riders paraded and stood with their teammates in front of the cheering crowds. As local dignitaries welcomed the riders and children carried banners indicating the rider’s nationality, bands played the national anthem of that country. The festival atmosphere was perhaps less frenzied than that of the rock concerts making headlines at the time, but was no less popular. Maico family member Wilhelm Maisch, Jr. remembers the average attendance of a championship motocross race at the time, in Germany, at 4,000 to 8,000 persons, with a maximum of 15,000. Events in the USSR could exceed 100,000.[10]

[1] Gunnar Lindstrom. Husqvarna Success (Stillwater, MN: Parker House, 2010), 58-63

[2] Interview with Bryan Kenney by David Russell, September 12, 2012, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[3] The actual full name of the CMC, one of the most influential off-road motorcycle clubs in America, began as the California Motocross Club. Over the years it evolved into the present Continental Motorsports Club.

[4] Interview with John Barclay by David Russell, February 22, 2014, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[5] Interview with Barry Higgins by David Russell, January 8, 2014, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[6] The Federation Internationale de Motocyclismo (Federation of International Motorcycling, or FIM) is the governing and sanctioning body for world motorcycle racing.

[7] Endless Summer, dir. by Bruce Brown (1966).

[8] On Any Sunday, dir. by Bruce Brown (1971).

[9] Interview with Jeanne Lokey by David Russell, January 12, 2014, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[10] Interview with Wilhelm Maisch Jr. by David Russell, (date not recorded), 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

David thanks for the trip down memory lane. I had no idea there was so much information about the early days of the American Motocross Team. I really enjoyed reading your story. For me next April will mark 50 years since I first raced in Europe. That’s way more then 1/2 a lifetime ago, yet my memories are still vivid and cherished. Still in contact with Bryan but we are moving on to ebikes now.

John, it sure wouldn’t have been possible to do that without your kind help! I kept having to pinch myself that I was ACTUALLY getting to talk to the folks I had read about, so many years ago, that had formed & raced as the American Motocross Team. Thank-you again for helping us learn our history! Dave

2 days ago, I met Bryan Kenney, and his wife Ann, at my hotel http://www.villaelisahb.com in Arequipa, Peru . I did not know his was such a legend of american and world motocross. We had a wonderful discussion in french (impressive after so many years out of France and we visited our VINTAGE RIDES ANDES garage ( http://www.vrandes.travel coming soon) with our 12 Royal Enfield Bullet 500. Timme was too short for a ride. Come back Bryan ! 🙂

Fascinating, Jean-Louis! Bryan did mention his involvement with art; I believe through his wife. Yes, he’s a treasure.