No products in the cart.

Ake Jonnson, Maico, Motorcycle Culture

Ake Jonnson: King of Motocross Part 2

RACING: HOPE, IMAGE, REALITY

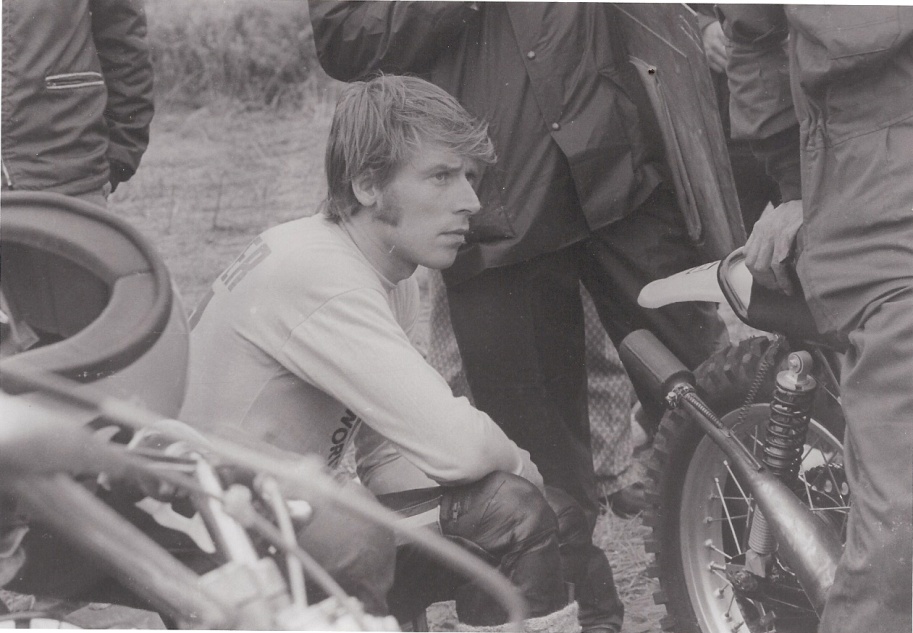

THE SUCCESS YEARS: AKE JONSSON

“Everything was possible:” the 1971 World 500cc Championship

1971 was another successful year for Maico and Jonsson. It did, however, also hold one of motorcycle racing’s bitterest stories of poor luck and defeat, for both him and Maico. Jonsson, while leading the 500cc championship series in Europe, was poised throughout the end of the series for his third and possibly best chance yet of winning the individual championship. Going into the final race, he led Roger DeCoster (Figure 96) in the series by one point, overall. While out in front in the first moto at the St. Anthonis, Holland, world championship race on August 22, Jonsson’s 400 Maico lost power and came to a stop. The motorcycle’s spark plug had come unscrewed from the experimental light-weight cylinder head, recently installed by his mechanic. Of a very thin alloy, it had, in the process of expansion and contraction (due to heating and cooling, and as yet unbeknownst to Maico engineers), allowed the new short-reach ½ inch spark plug to vibrate loose and come out. This situation occurred on two other occasions in the preceding weeks to other Maico team riders, but had both times been attributed to simply insufficient tightening of the spark plug. Maico’s ignorance of the true nature of the problem would be painful. While Jonsson easily won the second moto, his overall score suffered and DeCoster jumped ahead to gain the 500c world championship yet again for Suzuki. It was an example of the ever present role of chance on racing, and a heartbreaking day for Jonsson, clearly the better rider that day, but destined to not be world champion.

Jonsson was, by his own estimation in 1972, at the absolute pinnacle of his skill. Even DeCoster, perhaps the most famous single name in motocross over the decades and currently mounted on the amazing RN73 factory Suzuki, was unable to ride with him. Jonsson felt released from mundane human limitations, transcending even his superior abilities: “In the second moto [at St. Anthonis], I remember thinking, while going down the straights . . . that I had so much time. So much time to the next corner; everything was possible. I was going very fast; sometimes when you’re not in good shape, you can’t think about anything on the straight. But this time it was so . . . easy. Everything was going so well; there was no problem. I remember the race after that—the Motocross des Nations race in Vannes, France—I won both motos there, easily, too.” Although Jonsson and his teammates did take the des Nations title for Sweden, his best career chance at the individual world championship had eluded him. Soon after the spark plug incident in Holland and with the real cause of the incident still elusive, a fourth occurrence happened while Jonsson was practicing. His team was certain this time that the plug had been correctly tightened, and the actual chain of events, relating to the new, thin head, was finally deduced. Additional metal was welded to the top of the new heads, allowing the use of the old, longer spark plug, and the problem did not recur.

The new physicality of motorcycle racing

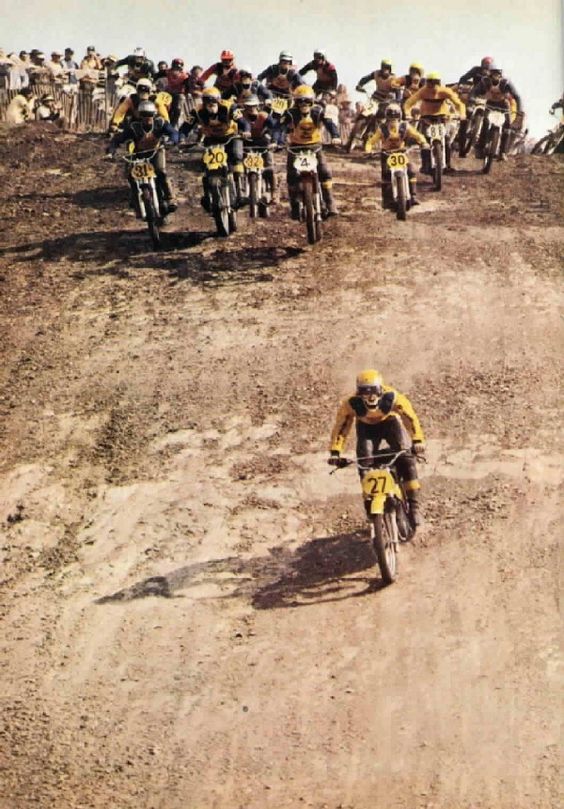

The crowning achievement of Jonsson’s time on Maico, the core of the “success years” for both, in his words, was certainly his phenomenal winning streak in the 1972 North American Trans-AMA series. Jonsson won nine of the eleven races outright, placed second in one race and third in another. His style, as Dennie Moore notes, was “Flawless. . . . like watching the Silver Surfer—something you’d animate and see made perfect. I remember him crashing in the first moto at Puyallup, Washington, and working his way up from last place to second place behind Mikkola (Figure 95) in that one forty-minute moto, then coming in first in the other for the overall win. I think Ake was probably the best motocross rider, ever.”[1] Racer and Maico shop owner Gig Hamilton likewise recalls Jonsson’s control and grace: “When Ake rode, he was just part of the motorcycle; he never man-handled anything.”[2] Jonsson’s riding style was a lesson in near-perfection: arms and legs notably straight back and weight aft on the jumps; fluid and seemingly-effortless over bumps and in the turns; always aggressive but ever under control.

Jonsson’s grace on a racetrack had much to do with his practice of cardio-vascular and muscular conditioning, learned from training for speed-skating. While motocross has occasionally been referred to as the “world’s toughest sport,” it was also a very new sport, and sports trainers and physiologists had yet to consider it and develop training programs. The Swedes were early proponents of a solid training program; Husqvarna’s race team trainer in the 1970s and 1980s, motocrosser Rolf Tibblin, conducted organized physical training programs for team members during the winter months at the Husqvarna headquarters. In Germany, Maico rider Adolf Weil developed and shared his own regimen for strength-training and conditioning with Maico riders. The Europeans’ propensity towards physical training for motocross racing’s more intense demands was one factor in their early dominance over riders in the United States—who appear in photographs and film footage of the time often spitting out a cigarette as the starting gate drops. Over the years, this realization that athleticism must lie at the heart of the sport widened the gulf between motorcycle sport riders and the by then entrenched American biker-rebel-outlaw formula. In motocross, at least, no longer could a rider in the United States ignore physical conditioning, show up at race and execute a few fast laps around a scrambles track, dependent upon skill alone, and succeed. Motocross, with its two forty-five minute motos, was a far different event, and Jonsson and his fellow Europeans showed the way forward.

Gig Hamilton was able to observe Ake Jonsson closely in these years, through his relationship to nearby Maico distributor Dennie Moore, who assisted the Maico factory team. Hamiliton enjoyed having Jonsson and the other team members visit his shop, and taking them into the Pennsylvania hills and flat-tracks to ride. Hamilton recalls Jonsson’s use of his off-time: “Ake practiced and trained a lot. For example, when it would rain, he would go out and ride in the wet grass and practice braking. He would just lock up the front brake; practicing keeping the bike straight. We grass will put you down quick, so Ake would just practice this all the time. One of the workouts I saw him do was to take a broomstick, tie a rope on it along with a weight, throw it over a bar a bit taller than he . . . and wind that weight in, using his hands! He’d wind that ten-pound weight up and down. I’ve tried it, and I can’t do it more than once or twice.” Attesting to the champion’s conditioning, Hamilton remembered a mid-western race in Ohio. “It’s eighty degrees, high humidity, and Ake pulls off the track after a forty-five-minute moto. I happened to notice the back of Ake’s neck; he had, like two beads of sweat on his neck. After a forty-five-minute moto!”[3]

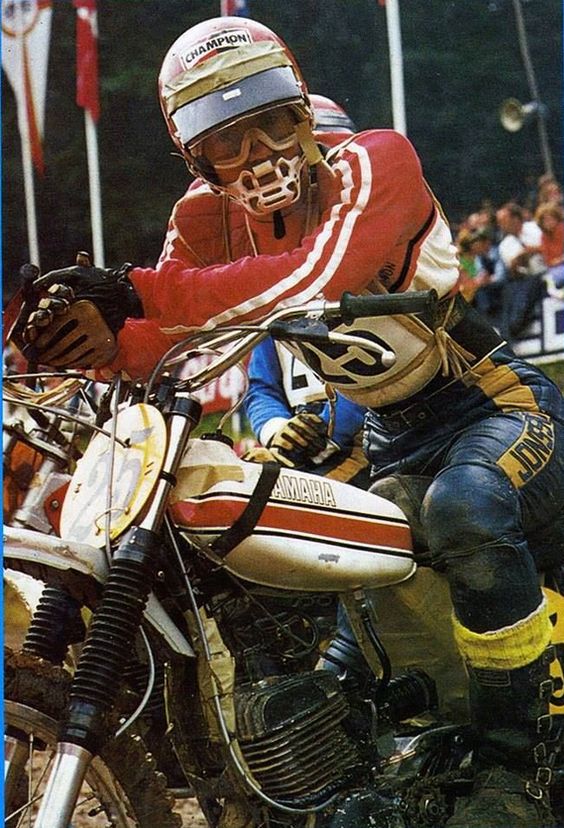

Changing mounts and cultures: from Maico to Yamaha

1972 was the end of Jonsson’s time with Maico. Yamaha offered him a contract with far more pay and the advantages of Yamaha’s vast engineering and financial resources, and Jonsson signed with them for the 1973 season. In hindsight, he believes the world championship would have been attainable in 1973 if he had stayed with Maico, but the Yamaha contract was too attractive to turn down. Jonsson was married with two children, and felt that he had perhaps three years left being competitive on the world class level. The actual earnings for motorcycle racers at the time, even the star European riders, were anything but phenomenal. Jonsson stated in 1971 that he estimated that his pay the following year (1972, when he was generally considered to be at least one of the finest riders in the world) would about equal that of an average professional engineer in Europe.[4] Considering the physical demands, the risk, and the short career of a professional racer, versus the expected working conditions of an engineering professional, the comparison is startling. (Salaries have changed over time. Within two decades, teenage motocross stars were earning hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.) Thus, whatever his reasons were, Jonsson left Maico, where he had for three years been on the cusp of not only being successful, but being world champion. He threw in his lot with Yamaha.

Jonsson rode for Yamaha from 1973 through 1975. 1973 in particular proved to be a difficult year, with Jonsson riding a 360cc machine which, like his old 360 Maico, he felt was not powerful enough. Apparently not satisfied with the Yamaha suspension as well, Jonsson’s machine featured Maico forks, something quickly noted by the press and surely an uncomfortable situation for Yamaha management.[5] A more powerful, long-stroke engine was provided in 1974, but half-way through that season he was arbitrarily told by Yamaha management to revert to the old 360 engine again.

Yamaha was fairly new to motocross racing, and management sometimes held unrealistic, simplistic expectations. Jonsson recalls, “We riders had to explain to them that motocross wasn’t like road-racing . . . where the one who has the most power wins. Yamaha in Japan had a hard time understanding that.” Despite the success Yamaha was having in the 250 class at the time, the early Yamaha open-class motorcycles, to which he was assigned, were “impossible to ride, at first.” It was not until 1975 that Jonsson received an engine he was comfortable with, and also when he felt that development of the large-capacity Yamaha motocross bike was finally adequate. Time, however, was not on his side. Jonsson had unfortunately spent his recent, prime racing years refining the Yamaha 500-class machines, rather than riding a competitive motorcycle which could compliment skill level. He spent his most promising years refining the motorcycles on which others might win. It had been a matter of economics for Jonsson, but the time with Yamaha was, overall, another bittersweet experience. Capping it all was Yamaha’s decision to drop out of world championship competition for 1976, for reasons which are not entirely clear.[6] This was perhaps Jonsson’s last year to race at his full potential. The former star, suddenly without a contract and after a false start with the small Italian Beta company, returned to Maico for two more lackluster seasons in 1976 and 1977. Interestingly, although Yamaha chose to withdrawal from team motocross competition that year, they actually had factory 1976 machines (that Jonsson had developed and could have adapted to immediately) ready at the season’s start. Jonsson, if he had known this, and with his now intimate familiarity with the bikes that he had largely developed, states that he would have obtained one of these bikes and campaigned it as a private rider, without sponsorship, in 1976. Once more, Jonsson’s career displayed the unfortunate reality in racing that “time and chance happen to them all.”[7]

Not yet ready to leave racing, Jonsson rode a Kramer in 1978. The Kramer was made by a Maico dealer in Germany, using Austrian Rotax engines and monoshock frames of his own design and manufacture. The Kramer’s frame, however, was inferior to other world-class machinery, and the Rotax engine proved to be less than adequate. Jonsson left Kramer after the 1978 season. With the traveling continuing to bear down upon him and his family, he elected to race yet one final year for his local Swedish brand, Husqvarna. In 1979 Jonsson left racing for good and opened his own motorcycle shop, selling Husqvarna and Yamaha. He prospered for the next three decades, selling the shop and retiring in 2007.

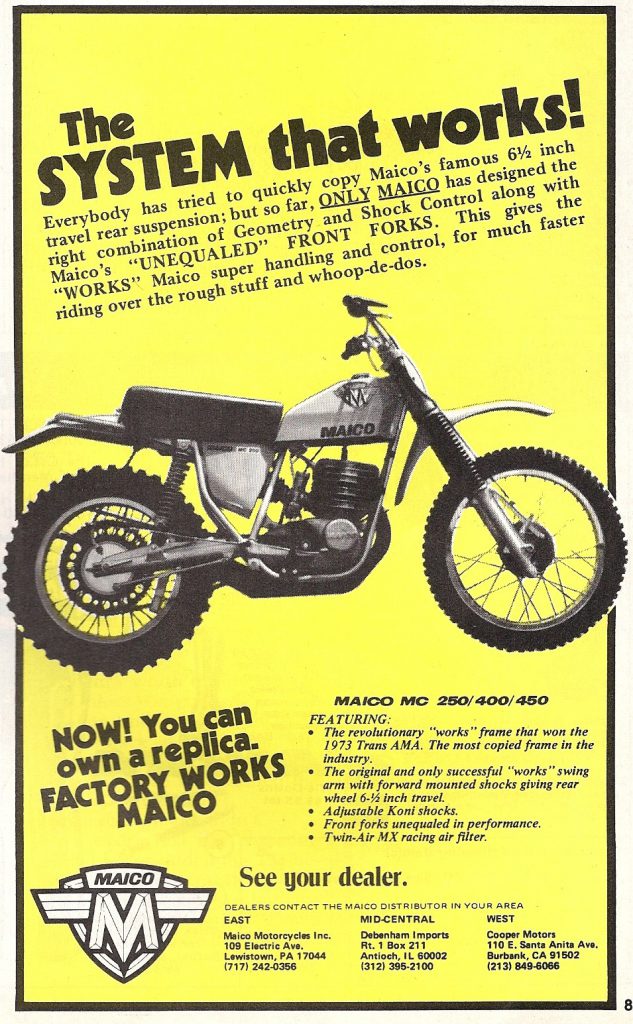

Maico, Yamaha, and long-travel rear suspension

An adjunct to Jonsson’s racing experiences on both Maico and Yamaha is his presence on the two teams at precisely the time period when long-travel rear suspension (LTR) was introduced. After considering the juncture of Jonsson, Maico, and Yamaha in the previous paragraphs, I will now briefly discuss the intersection of these three entities with LTR. LTR is possibly the single most important innovation in all of motorcycling since 1970, and certainly so for off-road motorcycles. Maico and Yamaha, coincidently, are the two companies which were to introduce this concept in 1973. Very soon after Jonsson left Maico to ride the new Yamaha monoshock LTR machines in 1973, Maico introduced its own twin-shock LTR machines. Having been with the two teams which pioneered LTR at the time of its emergence, he is in a unique position to recall the innovation’s history. The inevitable “Who thought of LTR, first?” question is a difficult and complex one to answer. To begin, let us consider the question in a 1973 microcosm of simply Maico and Yamaha. While Jonsson concedes that Maico engineer Reinhold Weiher was the first to arrive at an obviously effective LTR arrangement with his modified twin-shock LTR Maicos, he cautions that “they (Maico) were also watching Yamaha.”[8] As noted previously, Yamaha did enter LTR monoshock machines in European Grand Prix competition several weeks prior to Maico. Yamaha had actually first revealed its monoshocks as early as the previous year in Japan, in 1972, but whether word ever reached the other manufacturers is doubtful. To what degree Reinhold Weiher and Maico stumbled upon LTR independently or under the influence of Yamaha remains unclear. Weiher’s motivations were either to simply solve the rear wheel problem (as Selvaraj Narayana recalls in chapter 6.1); to increase rear wheel travel, after Yamaha’s lead; or, some combination of the two.[9]

Now, looking at LTR in a macro way, motorcycle engineering history must be considered. Both monoshock and forward-mounted (and “laid-down”) twin-shock LTR systems had been conceived and built long before 1972. The great Vincent-HRD machines of the 1930s incorporated a centrally-located shock-absorbing system, attached to the rear sub-frame, which allowed it to pivot and move independently of the forward engine/frame assembly. The Vincent arrangement is, in fact, very similar to the early Yamaha “single-long-shock-under-tank” systems. A variety of motorcycle makers incorporated twin rear shock absorbers in ways which could be called “forward-mounted” or “laid-down” by 1970s standards, though they did not provide significantly more suspension travel. British AJS Stormer motocross machines of the very early 1970s had the shocks mounted nearly as far forward on the frame and swing-arm as did Maico’s LTR design. In the United States, inventor Charles Cornutt manufactured long-travel shocks for use in the desert. And, interestingly, Husqvarana’s Silverpilen, used by Jonsson and many other Swedes as their first competition motorcycle, used a rear shock mounting design that surely would have been considered forward mounted and laid-down. Author and racer Gunnar Lindstrom recalls that, owing to the Silverpilen’s use of very light-duty shocks, early users were quickly ruining the highly-stressed units, and in response consciously un-did the arrangement which was to be a revolution ten years later in motorcycle suspension. The Silverpilen riders understood that it was the extreme stress of the forward-mounting that was so hard on the shocks. To remedy this, they mounted the shocks in a more conventional upright manner, farther to the rear of the swing-arm (and with less mechanical advantage), to lesson stress and make the shocks last.[10] (In one final turn on the Silverpilen story, Husqvarna would come around nearly full-circle. The factory used an almost identical laid-down frame design for their 1975 and later models.)[11]

Jonsson after Maico

Jonsson remained friends with other Swedish riders, but admits to having lost contact with most of those outside his home country. A personal tragedy for Jonsson occurred when old Maico teammate Willi Bauer, with whom he had often stayed while visiting the Maico factory, was severely injured. Bauer had signed with the German Sachs company, and was practicing on a prototype motorcycle in Scotland in 1978. While running at only moderate speed, Bauer hit an unseen hole and was catapulted over the bars. He was paralyzed for life.

Jonsson’s Maico teammate and mentor Adolf Weil (Figure 97) passed away on May 12, 2011. He had long ago left racing behind him, and, after retiring from the motorcycle shop he ran with his two sons, preferred a quiet life in Germany.[12] Unlike Jonsson, Weil remained with Maico for his entire racing career. If Jonsson’s is the face most associated with Maico, Weil’s is the second most familiar Maico representative.

Jonsson visited the site of the old Maico factory in Pfaffingen in the autumn of 2007. He had not seen it for thirty years. Part of the original complex still stood, including a machine room and the main assembly room. Fading Maico stickers were still affixed to the windows, as men in long robes and turbans strode about the grounds.

Ake Jonsson is now retired from the motorcycle business. When still running the business, he had on display in his shop two of his Maico racing bikes: the #27 (American series) and #2 (European circuit) machines. The #27 bike was a surprise gift to him by his son, Tomas, on the occasion of Jonsson’s fiftieth birthday. Tomas had obtained the motorcycle from ex-patriot Swede and long-time American citizen Lars Larson, who had purchased the bike in 1972 after the final race of the Trans-AMA series at Saddleback Park.[13] Jonsson also retained his 1975 Yamaha factory OW26 motorcycle.

Jonsson is justifiably proud of his racing successes, and still recalls his opportunities at the world championship, foiled by the occasional bad luck inherent in racing. Remembering the spark plug incident in Holland is still painful. Though fellow Maico team member Selvaraj Narayana recalls Jonsson as being so calm as to be smiling, Jonsson disagrees: “Smiling? No . . . I wasn’t smiling. No . . . it’s hard to lose.”[14]

Ake Jonsson is strongly remembered by riders in the United States who were part of 1970s off-road motorcycle sport. Several have even constructed replicas of his factory Maicos. These are the same men who were there at the birth of modern motocross in the United States, who read the magazines and were entranced by the smooth Swede on the exotic Maico. They perhaps were even able to watch him in person, smoothly pulling away from all challengers. Jonsson figures prominantly in some motorcyclists’ reconstructions of their own careers. Jonsson was the image many of them aspired to: a factory rider, successful, famous, and paid to do what he loved.

A significant aspect of Jonsson’s allure is his history of beating the finest riders in the world on a motorcycle that anyone could buy. Jonsson’s Maico was known to be a basically stock motorcycle; if he could win with one, perhaps they, on a Maico, could as well. As they grow older, this memory of talent fairly trumping advantage intensifies: “Ake, Ake, Ake!”[15] He was the best rider, mounted on the motorcycle that anyone could have. Ake proved that with hard work, desire, and an equal playing field, that any of them might triumph, as well. Jonsson broke the myth that winning at elite levels required something else that they, being common, were denied. He proved that motocross could be (if it not always was) a democracy and a meritocracy, not a sport where expenditure necessarily determined outcome. A million-dollar motorcycle was not required; Ake had shown them that.

With the passing of years, Jonsson likewise fixes on the significance of what he accomplished, beyond the painful missed opportunities. Whether he was world champion or not, he is still recalled by many as the greatest rider there ever was. A loose spark plug does not lesson Jonsson’s abilities. Jonsson values the time he had with Maico, as well: “The best and most interesting racing years I’ve had, were during the Maico years.”

Among the young riders in the United States who held Jonsson in high regard were three young men from California, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Tim Hart, like Jonsson, raced for Maico and Yamaha; Denny Swartz was an Ohio farm boy who won the last national race in the United States ever to be won on a Maico; and Brian Thompson is the suburban Pennsylvanian who helped to break the “color barrier” in American racing. They, like Jonsson, believed “everything was possible,” and next I will examine the lives and motivations of these young men.

[1] Interviews with Dennie Moore by David Russell.

[2]Interviews with Gig Hamilton by David Russell, June 19, 2007 and April 7, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eric Raits, “Ake Jonsson Profile,” Cycle Guide (March, 1971), accessed November 24, 2014 on www.akejonsson.com/interviews-html.

[5] Paul Boudreau, “The Scene:Hang Ten United States Grand Prix,” Motocross Action Magazine, (October, 1973), 30-31. The photograph shows Maico forks on Jonsson’s Yamaha.

[6] Yamaha’s temporary departure from racing in 1976 is reputed by some sources to be related to the tragic May, 1973 racing death of Yamaha road-racing star Jarno Saarinen. Author Colin MacKellar cites a need by Yamaha management to get the team “properly organized after the shambles of 1974 and 1975” (source: MacKellar, Yamaha Dirtbikes, 64.)

[7] Ecclesiastes 9:11 (Revised Standard Version).

[8] Reinhold Weiher and his innovation will be discussed further in chapter 6.1.

[9] Interview with Selvaraj Narayana by David Russell, June 27, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[10] Interview with Gunnar Lindstrom by David Russell, January 27, 2008, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Russell Motorcycle Sport Collection, Center for Pennsylvania Culture Studies, Penn State Harrisburg).

[11] Gunnar Lindstrom, Husqvarna Success (Stillwater, MN: Parker House, 2010), 25-8, 131. Although all these earlier designs would not be considered “long-travel,” in that they did not provide any more than the normal [pre-LTR] four inches of rear suspension travel, they do approximate the designs that later 1970s engineers would use to achieve greater and faster suspension travel. The AJS and Husqvarna Silvepilen designs did meet one aspect of LTR, though, in that they provided increased rate of rear wheel travel, by virtue of their mounting farther forward on the moment arm, assuming a similar damping rate as later shocks.

[12] Adolf Weil was contacted on behalf of the author by Wilhelm Maisch Jr. in 2009. He declined, however, to be interviewed, and “just wanted to enjoy retirement and his sailboat.”

[13] The multi-faceted Lars Larson was an assistant to Edison Dye in the latter’s importation of Husqvarna motorcycles and the promotion of lightweight sport motorcycles in America. Larson was also a nationally-ranked motocross competitor and a gold-medal winning member of the American International Six-Day Trials (ISDT) team.

[14] Interview with Selvaraj Narayana by David Russell.

[15] “Ake! Ake! Ake!” was the headline of a British Maico advertisement, circa 1972.

Hi,

I know the story behind the long rear wheel travel solution from Maico and the intriges in the factory,

specially the sabotage inside the teams.

I was factory rider at that time with Maico and my mechanic worked on that solution.

If you want to know the real story, contact me.

Gerrit Wolsink

Dr. Wolsink,

Thank-you most sincerely for your note, and I will be in touch. (For those younger readers, Dr. Wolsink’s motorcycle racing career spanned the 1970s in both Europe and the United States. He was a US GP winner on multiple occasions, and nearly won the 500cc World Championship, placing 2d and 3rd in 1976/1979, and 1975/1977, respectively. Wolsink is remembered by many thousands of motorcycle enthusiasts around the world for his Maico and Suzuki factory sponsorships and achievements on these machines.)

Dave